A 'Babri Masjid' in Bengal and the Shifting Politics of the Man Behind it

Beldanga (Bengal): On a winter morning along National Highway 12, in Chetiani near Beldanga, a region better known for its chillies, cauliflowers, signature gamchha towel and, in recent years, bouts of communal tension, a crowd began gathering.

Long before the speeches started, the numbers had swollen to over a thousand.

At the centre of the crowd stood a freshly dug plot and a man long accustomed to changing sides. Humayun Kabir, a Trinamool Congress (TMC) MLA from Bharatpur and a former minister with a long history of party-hopping, chose December 6, the anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya to lay the foundation stone of a mosque he insists must bear Babur’s name. The move has triggered sharp political reactions, raised questions about communal polarisation in the run-up to the 2026 assembly elections, and exposed the internal discomfort within the ruling party.

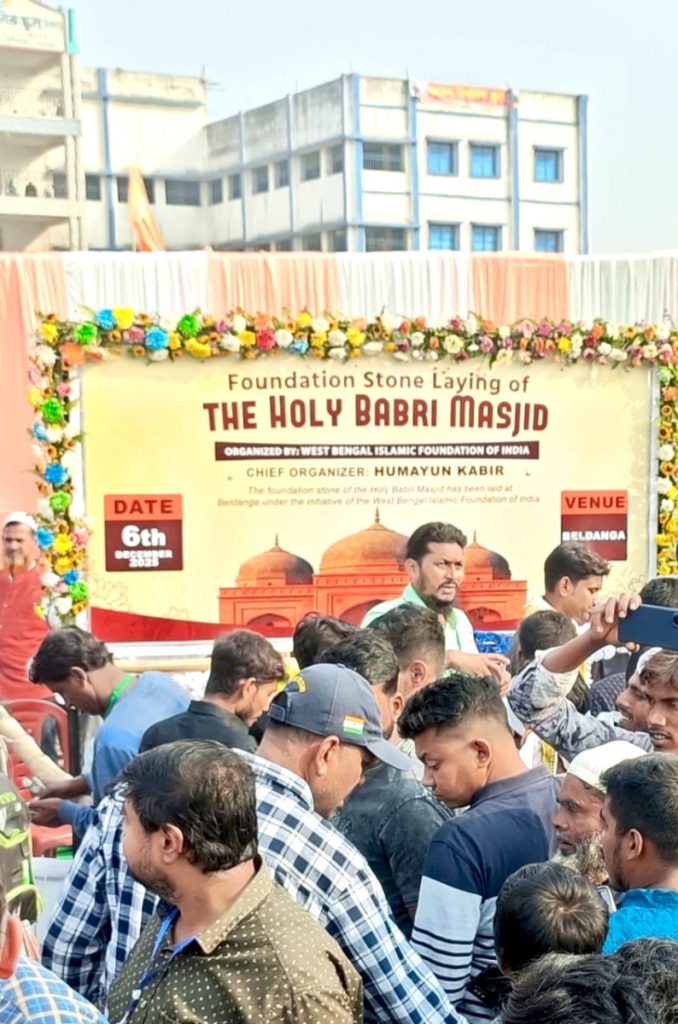

The gathering at Beldanga for the foundation-stone laying of the Babri Masjid in Bengal. Photo: Joydeep Sarkar.

Speaking to The Wire on the sidelines of the ceremony, Kabir said, “I had announced the construction of the new Babri Masjid on December 12, 2024 while still a TMC MLA. Why did no TMC leader care then? Because they did not take me seriously?”

At 62, Kabir has worn many political identities. He began as a Congress foot soldier under Adhir Chowdhury and was elected a Congress MLA from Rejinagar in 2011, the year TMC ended the Left Front’s 34-year rule in West Bengal. A year later, he joined TMC, just as the party was expanding its footprint in Murshidabad under the supervision of its second-most powerful leader then, Suvendu Adhikari. Kabir was made a minister in Mamata Banerjee’s cabinet.

The gathering at Beldanga for the foundation-stone laying of the Babri Masjid in Bengal. Photo: Joydeep Sarkar.

“Mamata-di gave me the responsibility of building the organisation in the villages,” Kabir recalls. With ministerial power and organisational access, he became the party’s point man in large parts of Murshidabad.

Within three years, however, he was expelled from the party for six years for “anti-party activities”. In 2018, he joined the BJP and contested the 2019 Lok Sabha elections from the Murshidabad parliamentary constituency, lost, and then returned to the TMC in 2021 to win the Bharatpur assembly seat. His second stint in TMC has been fraught with controversy, drawing repeated reprimands from the party.

On December 6, the party’s calculus around him changed.

'A different kind of emotion'

From early in the morning, people streamed into the proposed mosque site off NH-12. Hundreds arrived in e-rickshaws (called totos in Bengal) and tractors laden with bricks and cement. Some walked in balancing bricks on their heads. Thousands of volunteers handed out biryani packets, water and tea to supporters who had come not only from Murshidabad but from South Bengal as well.

“Mosques, we already have hundreds of,” says Mannan Sheikh from Karimpur in Nadia. “But because this one is in Babur’s name, Muslims feel a different kind of emotion. People want to carry the bricks and cement themselves just to feel like they are a part of it.”

The gathering at Beldanga for the foundation-stone laying of the Babri Masjid in Bengal. Photo: Joydeep Sarkar.

Abu Taleb, who came from neighbouring Domkal, links that emotion to a sense of neglect. “The chief minister is building temple after temple with government money,” he says. “What has TMC done for Muslims except use our votes, push our boys into crime, and make them accused in cases? Madrasa teachers aren’t being recruited in this era at all. Is that justice?”

For Kabir, the mosque is the centrepiece of a much larger project. From the dais, he announced that alongside the Babri Masjid, the 25-bigha site would eventually host “a 500-bed Islamic hospital, a medical college, a park, a restaurant and a helipad” at an estimated cost of Rs 300 crore. Alongside Kabir and several clerics stood Ali Afzal Chand, one of the BJP’s prominent Muslim faces known to have close links with the RSS.

If the show of strength rattled TMC, the timing of the party’s reaction has drawn almost as much scrutiny. Kabir was suspended barely two days before his grand show. Addressing a public rally, the chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who had camped in Berhampore, the district headquarters, called him a “rotten element funded by BJP”.

A furious Kabir responded with a bombshell.

“Before the last Lok Sabha election, to defeat CPI(M)’s [Mohammed] Selim and Congress’s Adhir [Chowdhury], it was the chief minister herself who told me to start a riot in Shaktipur,” he claimed. “Otherwise, the CPIM-Congress would have won two parliamentary seats. And now, just because I want to build a mosque, I have suddenly become a rioter?”

In April 2024, barely weeks before the Lok Sabha polls, Beldanga was rocked by communal violence after a minor altercation during a religious procession spiralled into full-scale clashes. The unrest left several injured, sharpened communal polarisation and turned the Beldanga-Shaktipur belt into one of Murshidabad’s new flashpoints in an election-charged year.

During the Lok Sabha campaign, Kabir’s communally provocative speech drew public outrage, but the TMC did not act against him. Within months, he was photographed at a social event with Karthik Maharaj, the very figure Mamata Banerjee accused of fuelling communal tension.

Humayun Kabir with Karthik Maharaj. Photo: By arrangement.

Inside TMC, many leaders now privately admit that Kabir should have been expelled long ago.

“He should have been thrown out after that communal speech,” says a senior TMC leader requesting anonymity. “But he was useful in certain pockets.”

Murshidabad has a Muslim population of 66.27% as per the 2011 Census. Seats like Rejinagar and Bharatpur, where the minority community form a majority of the population, give Kabir leverage that exceeds his formal organisational role.

“In the last Lok Sabha election (2024), he mobilised minority votes in the Baharampur constituency that helped our candidate, cricketer Yousuf Pathan, defeat veteran Congress leader Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury,” admits the leader.

Chowdhury is no fan of Kabir's.

“Kabir instigated riots. Instead of reprimanding Kabir, the West Bengal chief minister used his communal speech for electoral benefits. I-PAC, the political consultancy firm managing TMC, distributed video clips of the riot and speech across the constituency for further communal polarisation,” former Congress MP Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury alleges to The Wire.

TMC has not issued a point-by-point rebuttal of Kabir’s specific allegation regarding Mamata Banerjee's purported Shaktipur instructions. For opposition parties, this silence is telling.

“Humayun says he organised planned riots under instructions. Why have those who claim to prevent riots taken no action? And even after being directly accused of ordering riots, neither the chief minister nor her party has responded. Should this silence be taken as admittance?” asks CPI(M) state secretary Mohammad Salim.

'They threw him out because of the mosque'

A section of local TMC workers is openly resentful of the party’s action against Kabir. Despite his suspension, many minority TMC workers reportedly responded to Kabir’s call and arrived at the site in Beldanga, some carrying bricks and cement over long distances.

“He wanted to build a mosque, so they threw him out of the party,” Mosharaf Hossain from Paikgacha says. “Many of us can’t accept this in our hearts. So many leaders have gone to jail after committing crimes for TMC. Why weren’t they expelled?”

People carry bricks in view of former TMC MLA Humayun Kabir's plan to lay the foundation stone for a mosque, modelled on Ayodhya's Babri Masjid, at Rejinagar in West Bengal's Murshidabad district, Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025. Photo: PTI.

Kabir’s Babri Masjid project comes at a moment when both Trinamool and the BJP are vying to appear more firmly anchored in the Hindu religious identity. In recent times, the Mamata Banerjee government has funded a series of high-profile temple initiatives including a Jagannath temple in Digha, the Durgangan temple in New Town, and a proposed Mahakal temple on 17.41 acres in Matigara of Siliguri alongside grants of Rs 1.10 lakh to Durga Puja committees across the state.

“Was she elected as chief minister so that she could build temples with public money?” Kabir asks. “Minorities are being systematically deceived in West Bengal. They are used for criminal acts, then named as the accused and denied benefits. From Wakf to OBC issues, there is cheating everywhere. I will answer this betrayal.”

Political anthropologist Suman Nath sees this as a moment that can deepen the extent of polarisation in Bengal, but he cannot deny the element of emotion.

“During my fieldwork in Rejinagar in Murshidabad, I have seen posters demanding that the Babri Masjid be rebuilt. There has long been a sentiment around reclaiming the mosque and righting that perceived injustice, and Humayun Kabir’s recent move taps directly into that feeling," says Nath.

Meanwhile, BJP leaders organised a bhumi puja and shila pratishtha – ceremonies to make the ground holy before the building of a temple – for a replica of Ayodhya’s Ram temple in Berhampore, not far from the proposed mosque. The question now is whether Bengal’s fragile communal balance can withstand these twin pressures of the run-up to 2026.

Translated from the Bengali original and with inputs by Aparna Bhattacharya.

This article went live on December eleventh, two thousand twenty five, at forty-two minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.