In Dhubri, Muslim Residents Were Evicted First and Then Deleted from Electoral Rolls

Mass evictions of people living in slums across cities, using force, allegations of harbouring ‘illegal migrants’ have acquired phenomenal pace in the past few months. Calling out certain demographics, like Muslims and those who speak in Bengali, as non-citizens and housing them in ‘holding centres’ has made the exercise acquire a menacing character. The Wire reports on people vital to building city infrastructure, living on the margins, now suddenly finding their citizenship challenged.

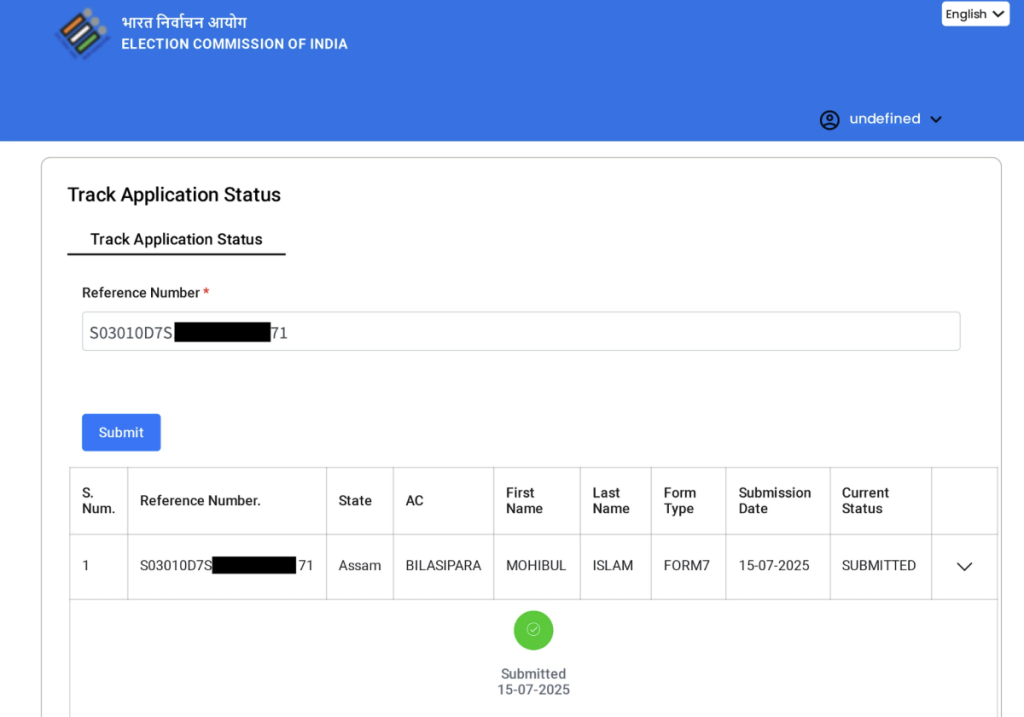

Barpeta (Assam): On the evening of July 15, 37-year-old brick kiln labourer Taher Ali was resting in a tarpaulin tent in Charuabakhra village. His home had been demolished by the district administration on July 8. Ali received a message that read: “Thank you for submitting form on VSP. Your reference ID is S0301D7S1*********531, ECI.”

Never formally educated, Taher Ali rushed to the tent of a neighbour who could read and write. The neighbour informed him that a “Form 7” had been uploaded to the portal of the Election Commission of India to remove his name from the electoral rolls. Form 7 used to file objections to the inclusion of a name in the rolls.

The message received by Taher Ali. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

On July 8, the Dhubri district administration demolished over thousands of houses at the proposed thermal power plant site near the Bilasipara area of the Chapar revenue circle. Residents claimed the count was 2,000. Officials said 1,400 were destroyed. Most of the evicted families are East Bengal-origin Muslims.

During a press conference on July 15, chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said, “Whomever we have evicted…we have deleted…the Deputy Commissioner must have already deleted their names from the voter list."

During a press conference on July 15, chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said, “Whomever we have evicted…we have deleted…the Deputy Commissioner must have already deleted their names from the voter list."

He also said that the widespread eviction drives are against “land jihad” – a bogey claimed by Hindutva forces alleging Muslims are part of a conspiracy to take over land.

Sarma said the evictions were to save "jati, mati and bheti" – race, land and homeland.

But Taher Ali recalls moving to the Charuabakhra village as a young boy.

His father, Kashem Ali (65), had officially transferred his voter registration to the village years ago by removing his name from the earlier voter list and enrolling in the current one in Charuabakhra village.

Ali said, “First they demolished our homes. Now they’re deleting our names from the voter list. I work as a migrant labourer. Wherever I go for work, they will ask for my voter ID. How will I provide that now?”

Ali says that he visited the Chapar Circle Office thrice for compensation of Rs 50,000 promised to landless families, alongside resettlement in the Boyjer Alga Part 2 village in the Athani Revenue Circle.

Taher Ali in his tent. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

Locals allege that several compensation cheques were issued in the name of heads of extended families who have passed away or no longer in charge of all the members and the families have, other the years, split into separate households.

Then, there is the matter of the government claiming that 600 fewer households have been evicted. Locals said that while the circle officer said 1,080 – still significantly fewer than the 1,400 official claim – families which received cheques are actually 800.

The residents claimed that they also found discrepancies in their names on several cheques received. One Hayet Ali said, “My name is Hayet Ali, not Hayed Ali. The bank won’t accept the cheque if the name doesn’t match.”

The Wire reached out to Shashee Bhushan Rajkonwar, the Chapar circle officer to confirm the matter of the compensation cheques. He refused to talk about it.

A villager's status on the EC website.

That same evening that Taher Ali got the message, Mohibul Islam, a private school teacher who also lost his home and school in the eviction drive, received a similar message with a different reference ID on the phone number linked to his voter ID. When he tracked the reference number on the ECI portal, he discovered that Form 7 had been submitted in his name as well. Mohibul said, “I was born in this village and never requested to delete my name from the electoral roll. Why would I do that?” he asks.

Mohibul Islam. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

Shahadat Ali (27) also received the notification on the same day. A graduate, Shahadat lost his home in the demolition and claims that his family has been living there since 1966. He says “I was terrified when I received the notification. This is humiliating. All they want to do is reduce Muslim votes in the constituency.”

Living in tarpaulin tents in the unbearable heat, without food, clean drinking water, or any certainty about the future of their children, and facing constant police harassment, hundreds in Charuabakhra now fear losing their citizenship, as many have received such notifications.

Chauabakhra, after the eviction drive. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

Several hundreds unaware

The four villages including Charuabakhra, Santoshpur, Chirakuta Part 1 and Part 2 have an estimated 3,800 voters. According to Booth Level Officers (BLO) in Charuabakhra Jungle Block and Santoshpur, ‘Form 7’ has been uploaded in the names of at least 1,260 individuals of Charuabakhra and Santoshpur Village on the ECI portal – supposedly by the District Election Office – for review or possible deletion from the electoral rolls following the recent eviction drive.

Kasim Ali (70), from the Charuabakhra Jungle Block, has lived in the area for decades. He currently lives under a makeshift tent in the village and has nowhere else to go. Ali is unaware whether a Form 7 has been submitted in his name, as his phone number is not linked to his voter ID card. Several residents living in temporary shelters, like Kasim Ali, said they are unaware of their current voter status. Many residents have changed their phone numbers over time. Others, especially those who are not formally educated, had linked their voter IDs with their relative’s phone numbers. As a result, many people in the area have not received any notifications. A teacher in Charuabakhra says that his phone number is linked to three persons' voter IDs – two of his nephews and the wife of one of the nephews. “I thought it was just another random SMS like the ones we get all the time. I only realised it was from the ECI when a neighbour asked me about it,” he says.

A woman cooks surrounded by tarpaulin tents in Chauabakhra. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain.

Chan Ali (27), Johur Ali (22) and Kanchan Khatun (20) are first time voters and cousins. Their homes too had been demolished in the eviction drive and they are living in tarpaulin tents. Chan Ali said, “Young voters like Johur and Kanchn are at great risk. If their citizenship is denied, they will face difficulties at every step in their lives.”

APDCL acquisition and the administration

The Assam Power Distribution Company Limited has demarcated an area of over 3,500 bighas for the power plant and erected hoardings throughout the area, which claim “this land belongs to APDCL and that trespassing without permission is a punishable offence.” Excavators are often seen rolling around and flattening hillocks.

People who have been living in Miyadi patta lands – land owned through permanent settlement – say they have been getting notices from the district collector's office saying that the land will be requisitioned for the Assam APDCL under the Assam Thermal Power Generation Promotion Policy, 2025. Many say they have been given 15 days to provide a written representation explaining why their land should not be requisitioned.

“We do not want to give our land to APDCL. Where will we go after that? The compensation they are offering us is not enough, says a Miyadi patta holder, who received such a notice, and lives in Chirakuta Part 1.

People living in tarpaulin tents in Chauabakhra. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

Meanwhile, evicted people currently living in makeshift tents said that police have been highhanded with them.

Kasim Ali says, “We were cooking in the morning of July 26 when several JCBs arrived with a group of policemen, some clad in black. They destroyed our tarpaulin tents and took away our utensils – along with the cooked rice and curry.”

Evicted locals also allege that the police have set fire to their tents and have been taking away their belongings. Jakir Hussain (42), a resident living on Miyadi patta land, says, “The police entered our home and threatened us, saying if we gave shelter to evicted people, they would demolish our house too. I saw police chasing away a group of people while they were resting under a tree. A policeman beat up one woman in front of me.”

In 2023, the land on which Kutubuddin Sheikh (35) and his family lived was registered as Miyadi patta land under the government's Basundhara scheme. His home was spared in a demolition drive on July 8, but also received the same message from the ECI portal on a Form 7 submission. Kutubuddin says that before the demolition, some of the patta holders were summoned to the collector's office. The collector, he says, promised them benefits under schemes like PM-Kisan and PM Awas Yojana, and in poultry farming efforts if they agreed to relocate to new and designated areas.

“We demanded all the promises in writing. The officials did not give it. Instead the collector threatened that they would remove our names from the land records and charge us for encroachment and destruction of forest land," Kutubuddin says.

A hoarding erected by APDCL in Charuabakhra Jungle block. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain

He further says that they were summoned to the DC office twice after the eviction drive and that there is pressure from the collector's office on them to move out.

A few land records downloaded by the villagers from the Integrated Land Records Management System (ILRMS) show that several bighas of government land within the demarcated APDCL area have been allotted as Miyadi land to people with surnames such as ‘Koch’ and ‘Bodo’. But villagers say that they have never heard of anyone with those surnames living in that area. They suspect that the government is aiming to transfer the land by claiming that it was handed over to them by these, allegedly false, owners.

On August 9, the administration dug up the only road in Santoshpur village, effectively cutting access off.

Voting rights

According to Section 22 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, the electoral registration officer (ERO) has the authority to correct entries in the electoral roll if a person is no longer an “ordinary resident” of the constituency. However, this can only be done after providing the person a “reasonable opportunity to be heard.”

Despite the clause, many evicted residents from Charuabakhra and Santoshpur say they have never received an official notice in advance. Instead, they claim they got only SMS alerts – written in English, a language most of them do not know – and for applications they say they never submitted.

Under Rule 21A of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960, the electoral officer is required to follow due process – including field verification and public notice– during voter list revisions. But many residents say that they did not receive any communication from the election office.

People living in tarpaulin tents in Chauabakhra. Photo: Kazi Sharowar Hussain.

Additionally, the Election Commission of India’s Manual for EROs recognises the rights of homeless persons to register as voters. The manual specifically states that no documentary proof of residence is required for homeless applicants. The manual reads, “In such case the Booth Level Officer will visit the address given in Form 6 for more than one night to ascertain that the homeless person actually sleeps at the given place.”

Sugata Siddhartha Goswami, the election officer of Dhubri district, tells The Wire, “We initially uploaded “Form 7” because no polling stations will exist there anymore. Once people relocate and provide new addresses, we will issue formal notices and re-enroll them as per their new constituencies.”

He adds, “After receiving complaints, we’ve stopped sending further notifications.”

Several lawyers The Wire spoke to say that this process violates electoral and other laws. Guwahati high court lawyer Aman Wadud says, “First the residents of the area have been forcefully evicted, and immediately there is an attempt to delete their names from the voters list. If these people can't prove that they are "ordinarily residents", their names could be deleted from the voters list. This is being done a few months before the assembly election. It is evident that they have not been evicted only for the thermal power plant, but there is a systematic effort to take away several constitutional rights.”

Update on August 16, 2025: After the publication of this report, election officer Goswami reached out to this reporter, noting that "till this date no deletion has been done in this regard." He also denied the "implication" in the article that the deletion process had been initiated on the basis of religion.

This article went live on August twelfth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-five minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.