'Mulk', a Majoritarian Guide to Tolerating the Good in a Minority

In a recent article titled ‘Questioning Muslims’ Loyalty’ in The Hindu, Mohammad Ayoob takes up the central idea of Muslim 'othering' depicted in movies like Garam Hawa and Mulk, and counters it by providing us with details of three Muslim soldiers who died fighting for India. He introduces them by claiming, “here are three irrefutable parts of evidence that show that the loyalty of Indian Muslims should be beyond doubt”.

But what if they hadn’t died for the country? Would the same logic be applied for the majority community? Additionally, what if at some point in time there weren’t any Muslim soldiers in the army? Does it tell us that the entire Indian Muslim community is disloyal to its country? This is precisely the nature of the discourse on secularism in India today, where one talks about equality while structuring a pre-existing dialogue on a given inequality that cannot be questioned or disputed.

A recent manifestation of that incongruity is the movie Mulk, that has been rather pejoratively described by some to be “pro-Muslim”. Following a clarion call by a Twitter user to ruin the movie’s chances at success for precisely those reasons, the IMDB rating of writer and director Anubhav Sinha’s Mulk dropped from 6.5 to 3.5, with more than 70% reviewers giving it a meagre 1 out of 10 stars. In response, Sinha said that he doesn’t care about these people and that he had already achieved his task of being heard. Promptly, commentators across print and digital media came out in support of the movie, invariably positing it as a response to Islamophobia, as a conscience keeper for us Indians who are often haunted by these bigoted notions of Us and Them.

There is no denying that the objective of the movie comes from a good place, where it aims to dismantle these fatuous binaries that are responsible for the physical and mental subjugation of the Muslim community across the country. Behind this veneer of liberal secularism, however, is a movie so riddled with contradictions and paradoxes that it inadvertently becomes a perfect analogy to the cautious discourse on secularism today which appeals to the goodness in us to tolerate the once-too-often misguided minority. The incontrovertible violent reality of the many, it champions, should not be extended to the rest. As Murad Ali tells Aarti in the movie, “Tum saabit karo mera pyaar mere mulk ke liye (You have to now prove my patriotism to my country)," it is up to the enlightened and loving Hindu to decide the fate of the apologetic Muslim.

Aarti does so with an unwavering belief in her case, leading to an emotional closing argument in the court where she knows she is right because she is a part of the family. Unlike everyone else in the courtroom who finds the evidence damning, she knows the family had nothing to do with any of it because she knows them. But what if she didn’t? What if it wasn’t about Murad Ali’s family but someone she didn’t know? What if it was one of the many real cases where Muslim undertrials are kept for decades on the suspicion of sympathising with terror outfits because of their surnames and social class? What about a Shahid Azmi who is killed for talking about these real people? Does the story therefore represent the plight of a community or the suffering of a cardboard family?

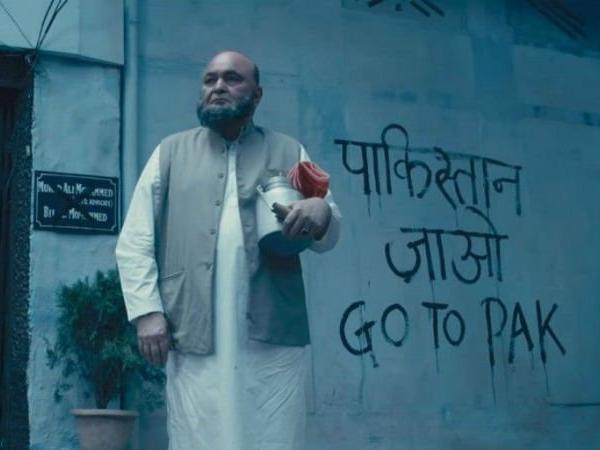

A still from Mulk.

At the heart of the movie is a flagitious Benarasi Muslim man, Shahid, who, on account of some scriptforsaken logic, decides to blow up a bus because he wants to improve the situation of Muslims in India. Right before his encounter with the ATS squad, however, he declares that neither the Muslim casualties of the attack (whom he doesn’t know at all) nor his family were Muslims really, and that he is fighting in the name of Islam. This is the foundation upon which the structure of the movie is constructed, and it is now up to the Hindu daughter-in-law to rescue the family from the consequences of one misguided member’s indefensible acts.

There are four different paradigms in which this act of redemption plays out – the family, the Muslim community, the larger Hindu community, and the blind-to-identities rule of law. The family responds by disowning Shahid’s corpse. The Muslim community represented by a series of surma-eyed men respond by congratulating Murad Ali for Shahid’s ultimate sacrifice. The non-Muslim society responds by ostracising the family because they find it hard to believe that they were unaware of the activities of one of their own. The law responds through a drawn out court battle where bigotry is personified in the figure of Santosh Anand, the public prosecution lawyer who foments and fulminates with salvos of vitriolic hatred against the backward minority community. Throughout the trial of the feckless Bilal and the righteous Murad Ali, Anand repeatedly generates laughter in the courtroom by capitalising on the natural crotchets of majoritarian prejudice. The only thing common between him and Shahid is their recognition of the inherent social, educational and economic backwardness of the community.

Sinha recently commented that he didn’t care to be subtle in his portrayal because he just wanted to tell his story. As a consequence perhaps, there is no doubt that Shahid and Anand are both the bad guys – the only two people, incidentally, who recognise the backwardness. The tragic reality about the petty prosecution however is that everything he says is undeniably true with respect to Shahid. Where he errs is in his extension of that belief to not just the family but also the entire community, and this is where the defence situates its case. While a majority of the prosecution’s case was about backwardness, the defence (and the movie) assiduously parries those questions that are actually germane to the minority politics in India.

In a movie about Muslims in India, where their economic and educational backwardness is used to describe their social presence, one only wishes that situated in a court of law, they had only so much as mentioned the Sachar Committee report and the Ranganath Mishra Commission report, among others, to truly tackle the social reality of their subjects. It is in its complete avoidance of the real issues that the movie is left wanting. With sentiments galore, this maudlin affair exposes a conspicuous lack of good research. Bilal, for instance, is buried with his head open, which defies the basic rules of enshrouding in Islam. This oversight is not the problem per se; it is a symptom of the larger affliction where the entire discourse of the movie is ironically constructed on the perceived reality of the community, a montage of sorts of things you may have noticed about this separate category of people who we should be compassionate towards despite everything.

An important parallel to the family is the character of Danish Javed, the head of the Anti-Terrorism Squad. It is he who makes and strengthens the case against the family because, we are told, he is prejudiced against his own community. When presented with an option, he is the one who chooses encounter over arrest. He is the one who is responsible for Bilal’s death. In short, it is a Muslim official who is responsible for the Muslim family’s troubles. Javed, in whose experience all terrorists have been Muslims, hunts bad Muslim families. And there is no dearth of the two stock categories throughout the movie. When the bad Muslims in the mosque approach the good Muslim Ali with an invitation to a prayer meet organised for Shahid, the latter reprimands them while they stand seething in anger, with one of the leaders’ fingers continuously traversing a tazbih (prayer bead). When they point out the ‘Go to Pakistan’ message painted on Ali’s walls, he tells them that if they don’t like such acts of vandalism, they should first stop celebrating Pakistan’s victories in cricket. For every prejudice out there, there is a diligent representation of people who prove it right.

A still from Mulk.

That is precisely where the movie fails in this great redemption project which amalgamates the discourses on backwardness and terrorism in such a way that you cannot talk about the former without first acknowledging the latter. Moreover, since the binary between the good and bad Muslim is so tediously facetious, a good Muslim knows that he cannot possibly do that. The most revealing aspect of the discourse naturally comes in its closing argument as presented by the judge – the voice of democratic justice. And in the exculpation of the family, justice is indeed met. The problem, however, is in the subtext of the judgement, which symbolises the great Indian communal problem.

In a judgement that is prima facie in favour of the defence, there are three important utterances that hold the key to our problem. The first is when the judge tells Murad Ali that he should not lose courage in the face of bigotry because it is the “fringe elements” alone who are behind it. The imputing of fringe elements, coincidentally, has also been the government of India’s standard response to majoritarian violence since May 2014.

Secondly, when responding to the prosecution’s naming of three Muslims who contributed to India – one of them obviously being A.P.J. Abdul Kalam – as exceptions to the rule, the judge says that that is “factually incorrect” and that he can name a hundred other Muslims who contributed to their country. Is that the answer to bigotry in a court of law? Would he have made the same comments for a non-Muslim convict? These nuances are at best adumbrated in the movie.

The third and the most significant point, however, is when the judge advises Rishi Kapoor’s Murad Ali to be careful about the activities of his children in the future. The patriarch should know what the young members of his family are up to and identify symptoms that could reveal their terrorising tendencies. In a scene where Ali bemoans this one great mistake of his life, he has a flashback of a scene where he was stuck in a traffic jam with Shahid because of an ongoing Urs celebration on the road ahead. When Ali says that there is no physical space for such activities in today’s public domains, Shahid responds by saying that spatial restrictions should be applicable to all religions. While this is a contemporary debate following the incidents in Gurgaon where right-wing outfits successfully objected to the spaces used for Friday prayers, the merits or the lack thereof in both sides of the argument is not the observation one is making here. What is important here is that this incident is what he is reminded of when he is thinking of symptoms that he should have identified.

Additionally, since any issue about the community’s marginalisation is only raised by Shahid the terrorist, the very act of perceiving them becomes a symptom of violent proclivities. A good Muslim, therefore, does not talk about the socio-political reality of her community. A good Muslim does not question the system. A good Muslim does not dissent. The majority, therefore, needs to recognise these merits in the minority and tolerate their presence and freedom to practice their religion.

This need to legitimise their agency by first acknowledging the many indisputable black sheep in every unit of the community weakens the movie at its very core. Because there is no cogent motivation behind any event, the movie becomes a sentimental mass drama full of contrived emotions. It tries to be both Garam Hawa and Khuda Kay Liye while retaining the nuance and minor felicities of neither. With its thematic equivocation and complete denial to identify the political and historical reality of an Indian Muslim, a reading of the movie as countering Islamophobia is not only myopic but also ill-informed. The only area in which it remains honest is in its sentiments and that is what it therefore restricts its fate to, tied up neatly in the end with a qawwali because, well, that’s (good?) Indian Muslims for you!

Sania Iqbal Hashmi is a Research Scholar at the Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

This article went live on August twenty-fifth, two thousand eighteen, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.