On the Trail of a Hindutva Poet and Influencer

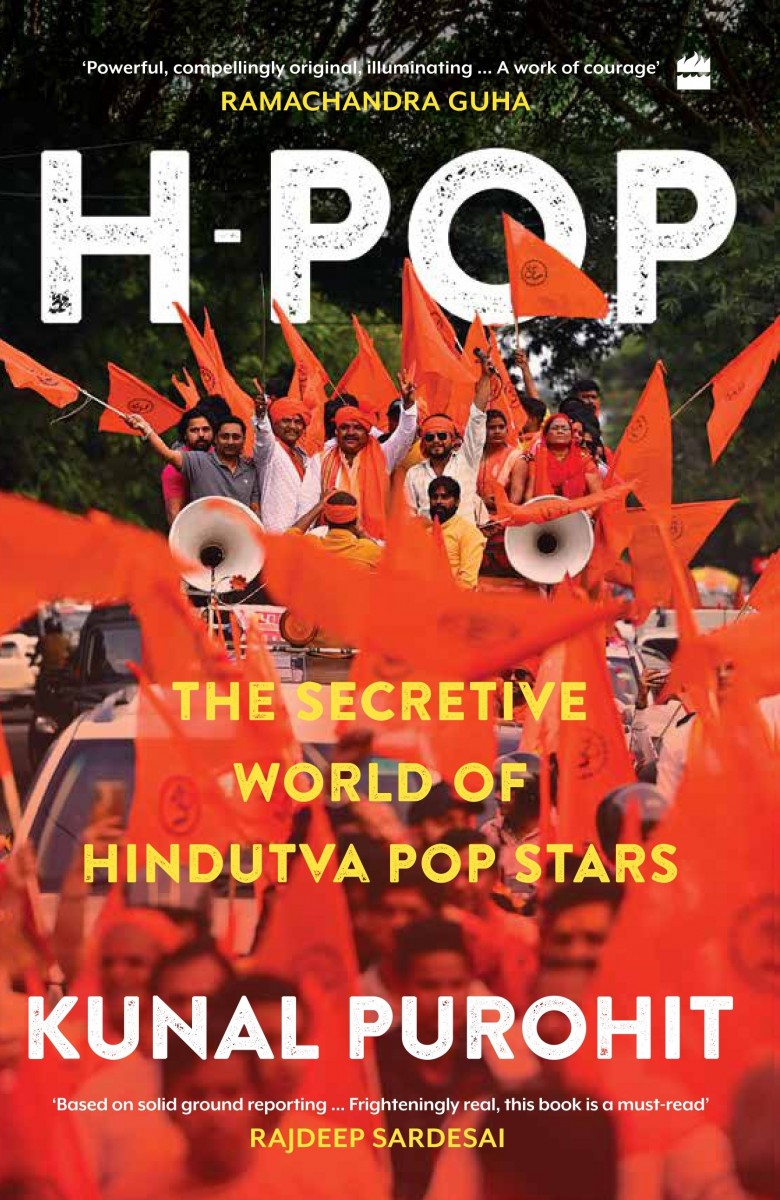

The following is excerpted with permission from Kunal Purohit's H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars, published by HarperCollins.

Weeks after that performance in Patna, India found itself in the throes of a catastrophic second wave of Covid-19 infections.

The government’s indifference towards the pandemic had turned out to be fatally misplaced. A devastating deluge of Covid-19 cases overwhelmed the country in the months of April and May 2021, leaving the country’s hospitals and cemeteries flooded. Patients found no place to go, nor did the dead. People were falling dead on the city’s streets due to the lack of everything, from hospital beds to oxygen.

For Kamal, all this had meant a slew of show cancellations and the possibility of a fresh financial crisis.

Ever since the pandemic began in 2020, Kamal’s income had fluctuated wildly. The money from live shows—which was the bulk of his income—had come down to naught. After the first wave of cases ebbed, live shows had slowly started taking off. The show in Patna was one of the first ones that Kamal had performed at since the pandemic. The second wave seemed devastating, and Kamal feared that shows might not resume that year at all.

Thankfully for Kamal and his ilk, the second wave of infections peaked in May and by July, cases had dipped substantially, and kavi sammelans had started taking place. I told Kamal that I was keen to attend some more sammelans with him, to see him perform.

He was getting calls to perform at some sammelans, he said. ‘Lekin kuch mazza nahi lag raha.’ It didn’t sound any fun, he would say, to justify why those calls weren’t materializing into performances. This, I later deciphered, meant that either the money offered was paltry or the show was too local for him to be associated with.

It seemed perplexing, because Kamal needed the money. His expenses were piling up. He had wanted to buy a new motorcycle for home so that his father did not have to depend on his brothers to be driven around. Kamal had his own expenses—from rent to the living costs that came with staying in a posh locality in Greater Noida, even if he shared it with two others.

Yet, for Kamal, saying no was important.

Kunal Purohit

H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars

HarperCollins, 2023

Kamal grew up in Gosaiganj, a small town with a population of less than 10,000 on the outskirts of Lucknow, a forty-minute drive from the heart of the city of nawabs.

It was there that he had witnessed his life’s first-ever poetry recital, a kavya goshti. The goshti was mostly a meeting of local poets, where they would recite their own material and discuss each other’s work. Kamal’s father, Ashok Varma, a connoisseur of poetry, knew all the local poets closely and attended these goshtis religiously. Slowly, Kamal started tagging along. In these goshtis, one of the poets who immediately stood out for Kamal was a local schoolteacher poet named Rameshwar Prasad Dwivedi Pralayankar.

Pralayankar is a nationalist poet, and much like Kamal, his poems deal with social and political matters. Back then, he would perform at locally organized kavya goshtis and Kamal, still in school, would attend these programmes and be blown away by Pralayankar’s talent, his commitment to the Hindu cause as well as his mastery over the Hindi language.

But as Kamal grew to emulate his guru, one thing struck him as odd about Pralayankar—for all his talent, Pralayankar had won barely any recognition outside of the state.

‘He has never been very career-minded about his poetry. Maybe because of his full-time job as a teacher, he never wanted to push his boundaries,’ Kamal told me. As a result, he would not be able to perform at bigger events that involved travelling. Be it Lucknow or Delhi, Pralayankar would end up saying no to many prestigious events because he could not afford to be gone from work for days.

As a way to make up for this, Pralayankar would accept all invitations he got around Gosaiganj, travelling across districts, even to smaller, local kavi sammelans, without regard for money or fame.

‘Woh toh kahin bhi nikal jaate the, apne scooter par.’ He would readily set off on his scooter for any kind of event.

Kamal used to be uncomfortable watching his guru do this. For him, readily going to smaller events, without any prestige or money meant that people took your talent and skills for granted. It also meant that you would get comfortable with whatever came your way, without having the hunger for more—bigger stages, more crowds, more money.

For Kamal, that was unacceptable.

That is where he had to make his break with his guru. Kamal was ambitious and had staked it all in the world of poetry. Money and fame were important. Each time he would get offered local gigs, with little prospect of decent money or exposure, Kamal would think of his first guru and inevitably refuse it.

It was in October 2021, around the nine-day festival of Navratri—at the end of which Lord Ram slays Ravana and marks the end of the war in the Ramayana—that things finally started to pick up for Kamal.

One of the first shows that he got was a kavi sammelan in Rasoolabad, a small town in Kanpur district, slightly over ninety minutes away from Kanpur city. The organizers of the event were the local committee that primarily organized the Ramlila, a dramatic re-enactment of the Ramcharitamanas over the nine days festival. The sammelan was meant to be the big showstopper and was slated to happen a day after Dussehra, on 16 October 2021.

Kamal said he would be free to perform ‘whatever he wanted’ at this event, which meant that there was no one to tame his political poetry.

Accompanying him to the sammelan was a mouth-watering prospect for me. Not just because of the event itself but the broader political context around it.

The political temperature across the country, but especially in UP, was soaring. The state was going to go to polls in four months, elections that would decide the fate of its Hindu nationalist chief minister and Hindutva icon, Adityanath. The elections would also be seen as a referendum on Modi’s governance since the party had dominated UP’s politics since 2014 when he came to power. The state sent eighty of the country’s 543 MPs to the Parliament. It was important for Modi to continue retaining a solid grip on it. But things had seemed to be slipping away.

The protest by farmers, against the three agrarian laws enacted by the Modi government, had been heating up. Just days before, three cars, containing BJP leaders and workers, including Ashish Mishra, the son of the Union Minister of State for Home Ajay Mishra Teni, ran over a group of protesting farmers in UP’s Lakhimpur Kheri district. Eight people, including four farmers, one journalist, two BJP workers in the cars and Mishra’s driver, were killed.

The killings had caused outrage across the nation. Protests broke out, with farmer groups and Opposition parties demanding that Mishra be arrested and his father Teni be sacked from his post to enable a fair investigation. Opposition parties made a beeline for Lakhimpur Kheri, but they were stopped from entering the district. The Congress leader Priyanka Gandhi Vadra was arrested, Samajwadi Party Chief Akhilesh Yadav was put under house arrest, while other Opposition figures were not allowed to leave the Lucknow airport. Five days later, Mishra was finally arrested.

The incident had shaken the nation, with viral videos showing the car ramming into the protesting farmers being played on loop on social media and across news channels. The BJP tried hard to deflect blame.

A crisis like this could hurt the BJP’s chances, and I had little doubt that the party would do all it takes to wrest the narrative in its favour. In this, Kamal and his ilk—poets and influencers—would be crucial to plant an alternative narrative.

I decided to pack my bags and head to Kanpur.

This article went live on November twenty-fifth, two thousand twenty three, at thirty minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.