Visiting Umar Khalid: A Manual for the Undertaking of Visits to Political Prisoners by Those Still Free

Today, September 13, is Political Prisoners Day.

In a short prose preface to a long poem cycle tiled The Requiem, the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova wrote about standing in the queue to visit a relative (was it her son ?) who was kept as a prisoner in a Leningrad prison during the worst days of Stalin’s grip over the former Soviet Union.

The fragment runs as follows :

Instead of a Preface

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror I spent seventeen months waiting in line outside the prison in Leningrad. One day somebody in the crowd identified me. Standing behind me was a woman, with lips blue from the cold, who had, of course, never heard me called by name before. Now she started out of the torpor common to us all and asked me in a whisper (everyone whispered there):

"Can you describe this?"

And I said: "I can."

Then something like a smile passed fleetingly over what had once been her face.

§

When a society begins to resemble a prison more than it does a playground, when things are no longer said as freely as they used to be, when the clenched teeth of panic and anxiety begin to make their grinding presence felt in every conversation – then – it becomes even more important to safeguard and cultivate a few patches of freely willed conversation, between those who are actually in prison, and those who are not yet confined.

So that those who are ‘inside’ may know that they are being waited for. And so that those who are still ‘outside’, with friends or family ‘inside’, may know that their waiting, through the ‘torpor common to us all’, is not in vain.

For the past two years (seven months more than Akhmatova’s 17), prisoner number 626710 in jail number two, in the Tihar Prison Complex in West Delhi, has waited patiently to be able to walk out of prison.

And I, and several others, have waited for him to do so. I feel that our shared patience needs to find its own way into the record of our time. So that posterity may look back on the queues outside the prisons in our cities and be grateful.

This is an attempt to make that happen.

Barring a few occasions during a sparse routine of trips from Tihar to the Karkardooma Session Court at the other end of Delhi, and occasionally, to Patiala House court, prisoner number 626710 hasn’t really had his day under an open sky, breathing the foul but free air of our city. The desire to cross the high walls of the prison, of this city within the city, and step on to the streets of the capital remains a hope, and a dream, that wakes the prisoner from time to time with startling vividness from the depths of sleep. When he thinks he is free, he knows he must be dreaming.

Sometimes, a drag on a cigarette borrowed from a generous prison guard breaks the monotony of Dr. Umar Khalid’s journey, (yes, that’s him, prisoner 626710). Sometimes it is a random snatch of conversation with a fellow inmate. Every time, there is a little bit more of the whirlwind of Delhi to be purloined in glimpses stolen by hungry eyes through the small grilled windows of the dark prison bus. But he has not yet walked free. On the rare occasions when the news comes of some other inmate, either in Tihar or elsewhere in the vast prison system of this country, getting bail, he rejoices, and then hopes for his turn.

Also read: Umar Khalid on His Two Years in Jail: 'I Feel Pessimistic at Times. And Also Lonely'

Endless bail hearings in a sessions court which ended with a dismissal of the bail plea, and the hearings of the appeal against that dismissal in the high court, which are currently underway, have so far denied Umar Khalid (and many others) that liberty.

[See ‘The Echo of Hearsay’ a three-part analysis published in Caravan (digital) of the arguments presented by the public prosecutor in the bail hearings conducted at the Karkardooma Sessions Court earlier this year, here, here and here.]

It has been 24 months, or 730 days, or, if you prefer, 17,520 hours, or 10,512,000 minutes, since Umar went into prison, after a day-long interrogation at the Delhi Police Special Cell Station at Lodhi Road on the September 13, 2020. September 13, 1929, also happens to be the day when the freedom fighter Jatindra Nath Das, Bhagat Singh’s comrade in the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army, died at the age of 25 in Lahore Central Jail, after he went on a prolonged hunger strike in protest against the conditions in which political prisoners were being kept. The September 13 is observed as ‘Political Prisoners’ Day’ in India.

Also read: Remembering Jatindra Nath Das, a Crusader for Rights of Political Prisoners

A week before Umar Khalid was arrested (talk about coincidences) on ‘Political Prisoners’ Day’ in 2020, he had come to see me. We had had a long conversation about the changing contours of the future.

Now, it is I, and other friends, who go to see him, as often as we can. He waits. Marking time with our conversations, measuring encounters with his smile. We still talk about the future.

The last time I met Umar in prison, 11 days ago, on September 2, he smiled, patiently, shyly, like he always does, and spoke of getting used to the elongated rhythm of carceral time; to seconds, minutes and hours stretching and sprawling to fill two whole years of non-time. And I am getting used to the rhythm of my visits. Once a month, for the past three months, usually on a Friday morning, I have a rendezvous with Umar Khalid, in the ‘mulaqat’ or ‘meeting’ facility of Tihar Central Prison, Jail Number Two.

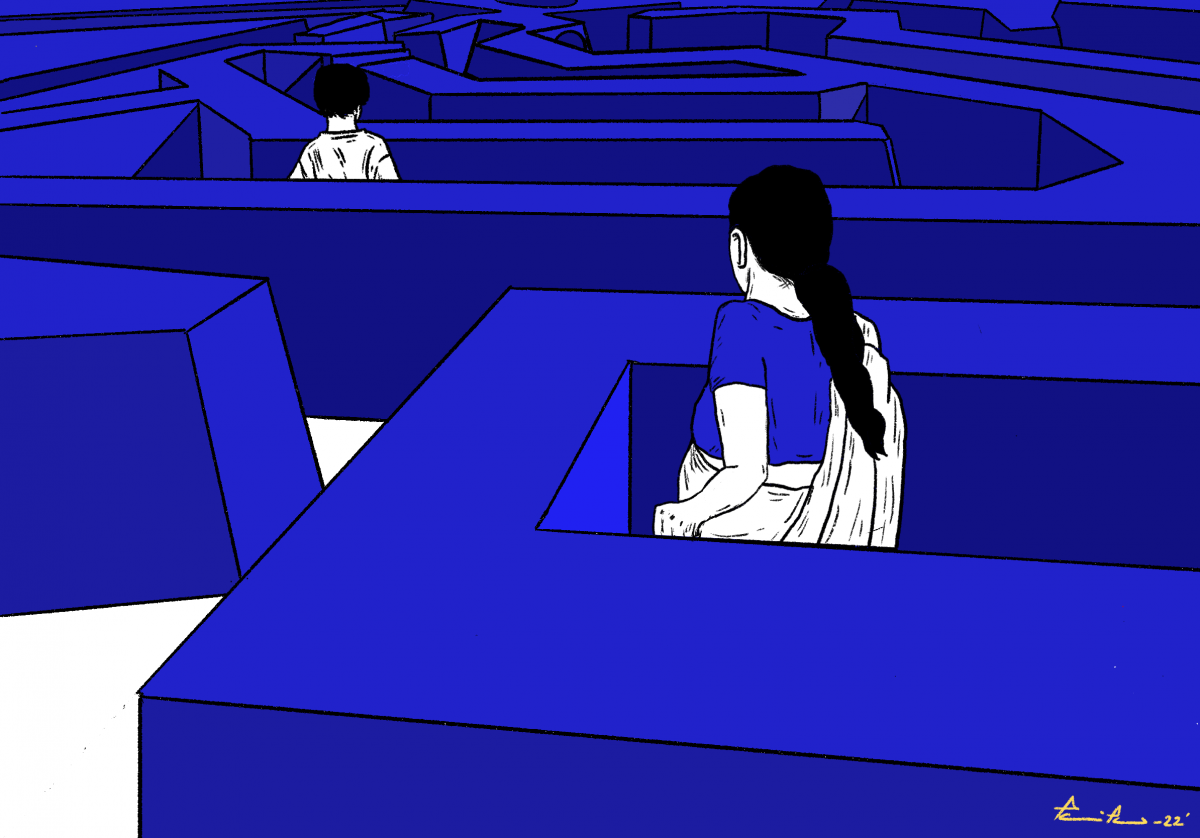

It’s not like in the movies. We don’t sit across a table in a hall full of prisoners and their families, everybody speaking loudly. Instead, the space I go into is a modest ‘L’ shaped labyrinth lit by tube lights, sectioned off into cubicles, with large grilled windows that act both as bridges and as barriers. The voices, are soft. No one screams. Through the grilles, like every other pair of prisoner and visitor, we are two standing blurs to each other, connected by two push button telephones. Your phone rings when your friend ‘inside’ picks up the receiver, and then you pick yours up, and facing each other you say, ‘Hello’. It is like time traveling back to what used to be the long distance phone call (STD) booths of yesteryear, except that your interlocutor is inches away, and the long distance between you and him or her is the distance between liberty and its denial.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

The path, from where I live, in Central Delhi, to that telephone in the Tihar prison complex crosses the South West ridge forest and the ring road, veers left off the road to the airport after Dhaula Kuan, cuts through the military cantonment, rises on to a flyover bracketed by two gigantic and listless tricolour flags on the way to Janakpuri, and then inclines briefly downwards as it speeds along the jail’s moralising, slogan painted wall past a petrol pump and a neglected crafts bazaar, (West Delhi’s ‘Dilli Haat’); as if the regime were signalling that the process of going in or coming out of the prison (even as a casual visitor) would have to take you on a trip through it’s might, its pomp, its circumstance, and its banal indifference.

And then, once you reach the gate of Jail Number 4, you walk up a short ramp to the window of the Public Relations Officer in a low outlying building, stand in queue and wait to make your ‘booking’ for a visit. With you, are other visitors. Mothers, fathers, sisters, wives, girlfriends and friends. If you’re lucky, they, and you, get a date for the next day. Once, a friend, who is smarter at these things than I am, was able to get through to the notoriously hard-to-connect-to phone line and reserve a ‘visit booking’ slot for me. But on two other occasions, visiting Umar has been broken into two trips to Tihar, once on a Thursday morning to take an appointment, and then again the next day, on Friday, for the actual meeting.

I am writing this to give readers a sense of what it takes to visit a friend who happens to be a prisoner. You need to set aside time, make plans, and follow procedure. In writing this I am conscious that in days to come, as the regime that rules us spirals deeper into the vortex of paranoia and insanity that it is creating, we may see more friends disappear behind prison walls. Having a friend, or a relative, in prison, simply because they have stood up and said something ordinary in defence of freedom or justice may become even more commonplace than it is today.

We had all better prepare ourselves for that, and for living up to the responsibilities that inevitably fall on the shoulders of those who are not yet confined. So if you find that you have a friend in prison, make sure to talk to their lawyer. They will prepare a list of approved visitors (and no, they need not only be immediate family) that will be cross checked and verified. You will have to provide identification details (Aadhaar card or driving licence will do fine) that mention your permanent address, state your father’s name, and then you will be put on a roster of approved visitors. When you go to visit, you should carry that ID with you (originals, not photocopies), so that you can be verified.

Visits can also be booked on the National Prisons Information Portal, here.

Telephonic bookings for ‘mulaqat’ at Tihar Central Prison can be made by calling the following numbers: 1800110810 (toll-free), +91-11-28526971 and +91-11-28520202. It may be worth noting that this does’t always work, and the most reliable method of ‘booking’ a slot for a visit remains the act of actually going to Tihar, queuing up at the PRO window, and physically obtaining a handwritten ‘chit’ with a date, number, and then turning up again, on the given date, before 11 am, for the actual meeting.

Each prisoner has a quota of visits per month, video calls, and phone calls (from the prison communication system), which must be divided up between the people on the prisoners approved list of visitors. It is best to have one person (from amongst the prisoners friends or family) who takes charge, and allots time to the different friends. In Umar’s case, the person who rations out and administers our visiting dates with cheer and humour, is his partner. She keeps a watch on who gets to visit how often, and make sure that Umar gets to see each of us by turn. She is like a curator, distributing encounters with a friendly efficiency that lets us all, and Umar, get our share of time with each other.

I strongly recommend that you set up a ‘network of friends’ if you have a prisoner friend, and that you give someone within this network such a responsibility. That way, everyone in the network gets a stake in maintaining contact with their prisoner friend. It brings a breath of fresh air into the prisoner’s life, prevents the atrophying of time that inevitably accompanies the monotony of prison life, and helps everyone concerned feel that they have a stake in the life of their incarcerated friend and comrade.