As the East India Company Expanded, its Relationship With Britannia Kept Changing

From 1648 to 1861, the East India Company’s headquarters were on Leadenhall Street, just down the road from the Bank of England, in the City of London. East India House was rebuilt twice, with new areas being constructed on both occasions for the display of artworks.

Unsurprisingly, these paintings and sculptures showed the men who served the Company as soldiers, ambassadors, administrators, and kings. The only female representations inside East India House were personifications of territories or virtues. Britannia, the symbol of the British state, appeared most frequently, and was often accompanied by a woman representing India or Asia.

Two sculptures of Britannia were specially commissioned by the East India Company as part of East India House’s reconstructions in 1730 and the late 1790s. The first of these, a marble relief titled “Britannia presented with riches from the East”, is one of the oldest known representations of Britannia in British art. The other was part of East India House’s monumental entrance portico. Both sculptures show Britannia surrounded by women who represent either territories or virtues.

The white marble relief of Britannia, made by John Michael Rysbrack, was placed inside East India House in 1730 as part of the building’s reconstruction by Theodor Jacobsen. It shows her seated on the left, being approached by three women who represent India, Africa and the Middle East. India is shown at the front, proffering a casket of treasure to Britannia. In the sculpture’s lower right side, Father Thames is shown lounging in front of an athletic man who is busy securing a crate of goods. The sculpture was installed above the fireplace, inside East India House’s perfectly cubical Directors’ Court Room. This was where the Company’s decisions were made by 14 of its highest-ranking shareholders. In 1730, when the sculpture was installed, the Company’s prime objective was to earn profit through trade. Fifteen years later, the East India Company founded a private army in South Asia and began its transformation into an imperial power.

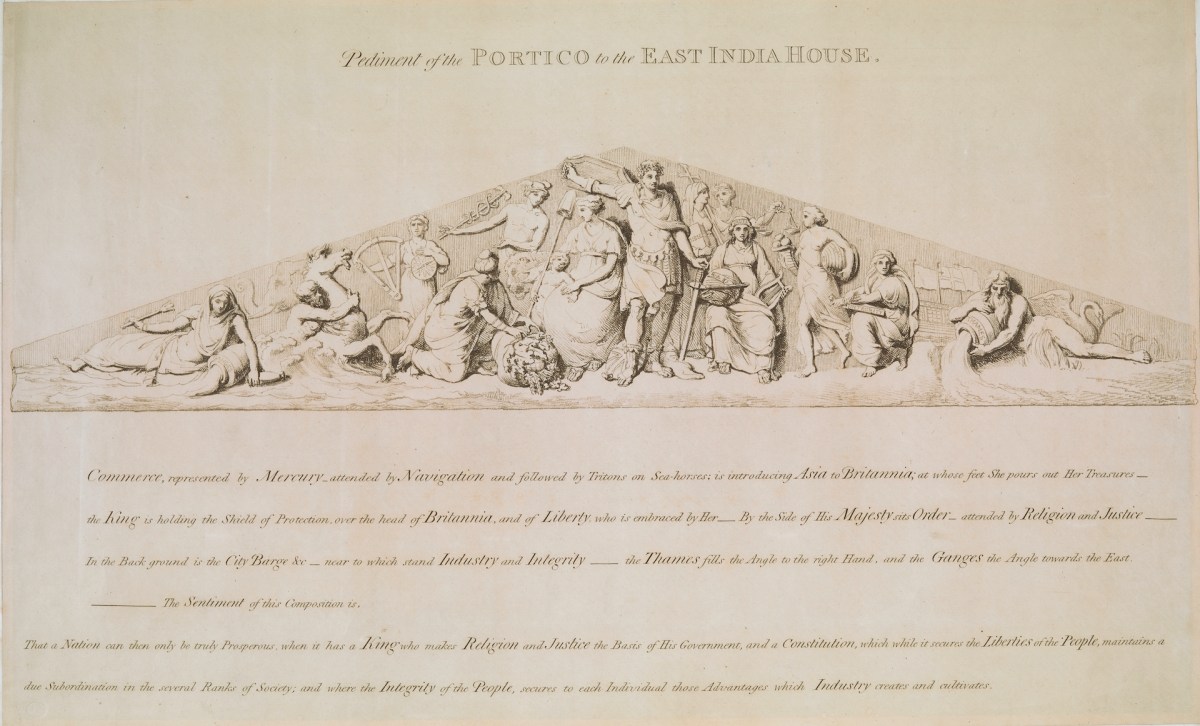

The other sculpture of Britannia, completed in 1798, was by John Bacon and was part of East India House’s second reconstruction by Richard Jupp in the 1790s. It was positioned on the outside of the building, on the portico above its main entrance on Leadenhall Street. The figures surrounding Britannia are completely different from those in the previous sculpture. Asia kneels before Britannia, presenting her with treasure. Africa and the Middle East are gone and have been replaced by female figures representing concepts and virtues such as Navigation, Integrity, Justice and Liberty. King George III, dressed in Roman military uniform, stands beside Britannia, holding the “shield of protection” over her head. At the far-left corner of the composition, The Ganges reclines supinely in a sari, while Father Thames takes his place at the far-right.

John Bacon’s sculpted pediment on the façade of East India House, unveiled in 1798. It was destroyed when East India House was demolished in 1862.(British Library, P2203)

Detail of above showing Britannia with Asia at her feet and King George III at her side. (British Library, P2203)

The busy sculptural programme on the new entrance portico publicly expressed how the East India Company wanted to be publicly perceived. Anyone who walked down London’s Leadenhall Street in 1798 would have recognised Britannia seated at its centre. This is because a year earlier, in 1797, the new cartwheel penny had been minted. It was the first coin showing Britannia to be mass produced with steam-driven machinery.

Britannia on the cartwheel penny, 1797. (Screenshot from the Royal Mint’s website)

Between the 1730s and the 1790s, the East India Company transformed from a trading body to an imperial power. These changes can be traced by looking at the two Britannia sculptures. The marble relief completed in 1730, sequestered within the most private room of East India House, symbolised Britain’s commercial wealth, which relied on trade with India, Africa, and the Middle East. In the following decades, the Company emerged as an imperial power by establishing an army and waging brutal wars in India. By the late 1790s the East India Company was a political entity that sought a benevolent public image. The sculpture of Britannia above the entrance to East India House was recognisable to anyone with a penny in their pocket.

Jennifer Howes is an art historian and archeologist, and is the author of The Art of a Corporation: The East India Company as Patron and Collector. She tweets at @jhowesuk.

This article went live on October seventh, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.