Birju Maharaj and Munna Shukla Had Different Approaches but Shared Singular Love for Kathak

Barely into its third week, 2022 has delivered another devastating blow to the arts community, and in particular to the Lucknow gharana of Kathak.

In the wee hours on January 17, the doyen of Lucknow gharana Kathak, Pandit Birju Maharaj passed away, leaving behind his family, disciples, associates along with his legion of admirers. But barely five days prior to Maharaj’s death, his disciple, another stalwart of the Lucknow gharana, Guru Munna Shukla too had passed away at age 78.

The news of Birju Maharaj’s passing, barely a month before his 84th birthday, spread instantly across news and social media platforms, whereas Munna Shukla’s was shared more privately among his family, his grieving disciples and other admirers. In death, as in life, the two unparalleled artistes exemplified their striking similarities and differences.

Brilliantly talented, groomed from childhood into a world where Kathak came first and last, where upholding tradition was an unquestioned purpose in life, their vision was at once focused and expansive, because with every breath of Kathak that they drew – and it was every breath till the very last – they were aware that Kathak includes a vast universe of arts and thought and philosophy. Thus there was no hint of blind repetition in their choreographic works or in their individual dance, but always a freshness and a vitality that sprang from their own thought processes and personalities. And since their personalities were quite different, the work they produced was necessarily of strikingly individual quality.

Also read: Legendary Kathak Dancer Birju Maharaj Passes Away

While Birju Maharaj was the son of the legendary maestro Achhan Maharaj, Munna Shukla was the son of Achhan Maharaj’s daughter Vidyavati. Thus Birju Maharaj was his ‘mama’, although he always referred to him as Maharaj ji and not many outside the Kathak fraternity may have known that they were related, uncle and nephew.

Munnaji began his training under his father Sunderlal Shukla. Granted the Government of India’s National Scholarship in 1964, he became a disciple of Birju Maharaj. Achhan Maharaj’s younger brothers, Shambhu Maharaj and Lachhu Maharaj, were uncles from whom he also imbibed a great deal.

Kathak exponents Birju Maharaj (L) and Guru Munna Shukla (R). Photos: Facebook.

Gifted performers and accomplished teachers

In an interview during the summer of 2010 when I asked Munnaji how his approach to dance and choreography had changed over the years, the guru, by then retired from the post of Sahachari Pradhyapak at Kathak Kendra, said he had started to think more about the metaphysical questions which influenced his themes. Guru Munna could come across as austere and at times reticent to those only formally acquainted with him. His longtime disciple Nisha Mahajan, commenting on the influences on his work, mentioned the impact of Shambhu Maharaj’s ability to interpret a text to bring out the nirguna (a formless or intangible aspect of the Supreme) philosophy.

Birju Maharaj, contrastingly, remained like his idol, Krishna of Vrindavan. Perhaps more than the philosophy behind the lyrics, he danced to and choreographed for other dancers, what became apparent were the colours and the imagery, the intuitively felt myriad emotions exchanged between devotee and godhead. Even when he danced to the recordings of the somber and profound Pandit Amarnath, whose Sufi bandish-es induced a meditative state in many a listener, Birju Maharaj highlighted the rhythmic underlayering and danced with a sense of fun, like the child Andal played with the garland that her father had hidden, hygienically safe, before offering it to the Goddess. He always imagined Krishna as a 10- or a 11-year-old boy, Maharaj told me once in an interview.

"How can Krishna grow old and sober?" he said.

He also spoke on the same occasion about the jwala (flame) that dance ignited within him. After practising for several hours, he said, when he was a young boy, he would pick up an instrument to play it, and later he retained this inclination, for “sitting in a mehfil and singing”. Or, he said, he would walk alongside flowing water, to calm that “jwala”.

Munna Shukla likened the art itself to the water element, describing it once in an informal conversation as an ocean of bliss in which he was “joyfully and continuously drowning (doobte jaa rahe hain aur anand lete ja rahe hain)”.

Whatever the varied nuances of their dance motivations and inspirations, the two were equally known for the virtuosic technique that dazzled and bewitched audiences as they performed solo in their heyday, and which their carefully groomed disciples displayed in their choreographic productions.

Both the gurus played with tala in their unique ways. Rhythmic complexity was embedded in Guru Munna’s works without any overt attempt at drawing attention to the skill, as if it merely ran in his blood – which indeed it did.

Maharaj explained the phenomenon of living with an acute awareness of rhythm thus: “All of life is time (Poora jeevan hi samay hai). In every event, I see its underlying rhythm.” Time, when framed, is rhythm in art. So the throwing of a ball, the tiger creeping up on its prey, even mundane situations, like traffic or dialing a telephone, transformed themselves into rhythmic patterns before his senses, and he, in turn, performed those rhythmic patterns with all the vibrancy of a story with beginning, middle and end.

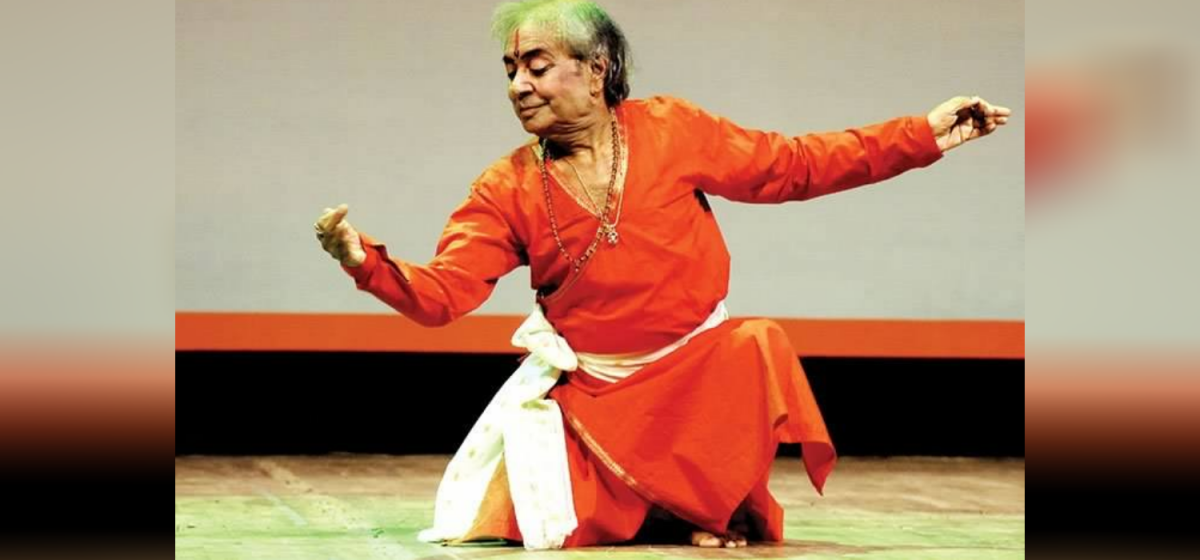

Pandit Birju Maharaj. Photo: Twitter/@sureshpprabhu.

Perhaps it was the very organic source from where these creations sprang that ensured that audiences, including those who knew nothing about the technicalities of Kathak, eagerly devoured his rhythmic stories, while other dancers, brilliant performers themselves, failed to engender the same appeal in replicating the very same tihai-s.

The most striking difference visible to the outsider, though, stemmed from the fact that one was the guru of the other. Munna Shukla was one of the few ganda-baddh disciples of Birju Maharaj (referring to the thread tying ritual that symbolises a deep and lifelong acknowledgment between disciple and teacher, laying a responsibility on both that is considered greater even than the usual guru-shishya bond). He mentioned once that as a guru, he would not consider tying the ganda for any of his own disciples, “especially while my guru is alive”.

At an event organised at New Delhi’s Saraswati Music College in 2016, he stated, “The shagird (disciple) is best off in the shade. The limelight is for the guru.” This was the motto, it seems, for the way he lived his life vis-à-vis Pandit Birju Maharaj. Whatever his accomplishments or erudition, gained through his reading, deep pondering and creative explorations, and his mastery of theory and technique, Munna Shukla never seemed to claim attention to himself – although awards and loyal disciples did come in the natural course, like the proverbial bees to honey.

At the same SMC event – which was organised to introduce youngsters to the now nearly obsolete concept of ganda-baddh discipleship – Guru Munna advised students on what to seek from the ubiquitous phenomenon of workshops. The main purpose, he said, when attending a workshop led by a great guru was not to pick up a composition, but to understand how the guru “sits, stands, thinks [perceives dance].”

It is such subtleties of the approach of both these titans of the Lucknow gharana that will be greatly missed, along with their vibrant personalities. As for gems of wisdom, they were both gurus who embraced their responsibilities as their destiny. Gifted performers, after all, fade with the physical prowess of the body. But their ability to teach, when guided by an inner conviction, became more valuable. Their greatest service to the field of Kathak will be the flow of knowledge that they allowed to pass through their individual selves to countless meticulously trained disciples.

Leave alone the innumerable students inspired and touched by attending workshops, especially the worldwide ones conducted by Maharaj, it is the work of the serious disciples that each produced which will ensure the continuity of the tradition. This cannot be doubted, even when the Lucknow gharana is reeling from losing two of its greatest pillars within one week and the world enters its third year of a Coronavirus pandemic that has halted so much of art activity. To mould one serious and accomplished dancer is a major feat. These gurus produced not merely accomplished disciples but gurus in their own right.

The guru and the disciple, the uncle and the nephew, have left their ailing physical bodies, and those of us who believe in an afterlife would like to think of them dancing and creating with renewed blissful vigour in an immortal form. As teachers, as performers and as lifelong students, both Birju Maharaj and Munna Shukla laid their reverential devotion at the feet of goddess Saraswati. So the mind’s eye takes comfort in imagining the two darlings of Saraswati back at last after a lifetime of creative adventures, dancing before her in unalloyed joy. And the disciple is perhaps more joyful still, because in his very last act on earth, that of leaving it, he made sure to leave before his guru. True to the artiste’s creed that all juniors complete their performance before the turn of the ustad. Gurus teach even in their death.

Anjana Rajan has been writing on the arts, literature and society for nearly 20 years. She is a former deputy editor of The Hindu, a dance exponent and theatre practitioner.

This article went live on January eighteenth, two thousand twenty two, at thirty-eight minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.