Delhi’s Khirki Masjid – Once a Shared Space of Everyday Life, Now a Contested Site

We never went inside. Girls would never enter the place. You go, we will stay at home, said my 50-year-old aunt.

Show the tourists something more interesting. These are just ruins, said an uncle.

Yes, what will we do there anyway? I’m going to the mall, said my 16-year-old cousin and neighbour.

Do you know we used to play under the domes! I wish the monument were cleaned so I could take my grandchildren there, said the white-haired grandfather of four.

Growing up in the vicinity of a historical monument is a special experience. Those who embrace it as part of the spaces that mould their everyday lives, see that connect as a fluid pact between past and present, holding out a promise for the future.

But there are junctures, like our times, when monuments become ammunition for narratives seeking to polarise society. A monument becomes important not for the way it reflects the lived experience of the local community, echoing with the laugh of a child or the warmth of her grandfather’s memories, but the manner in which it can be used to further a divisive narrative. The grand, 600-year-old Khirki Masjid (mosque) in Delhi, after which the village of Khirki gets its name, is no exception.

Bird’s eye view of the fortress-like Khirki Masjid, surrounded by the urban village of Khirki. Photo: Ekta Chauhan

I grew up looking at the Masjid’s majestic domes from the roof of my house in the village. We had what would now be called a “heritage view”, as did most of the houses in Khirki, an urban village in the heart of Delhi. This was during the 1990s when buildings were yet to go vertical in our sleepy neighbourhood of around 90 families of Chauhans, who trace their origins to a single ancestor, Khoobi Singh, said to have migrated to Delhi in the 12th century, as mentioned in Khirki’s genealogical records. The community of Khirki comprises this clan of Chauhans and several smaller groups of families.

I assumed, rather naively, that the localities in which my school friends lived also had a “qila”(fortress), as the Khirki Masjid was referred to in our neighbourhood. Long before I decided to pursue History as a subject in college, I frequently found myself in the midst of uncles, aunts and cousins having passionate discussions about the qila in the village. They would narrate stories about it that bordered somewhere between the mythical and the historical, which always seemed to have some connection with their community’s past or present. The discussions would end with a reiteration of the need for the community to protect what remained of its identity as “Khirkiwallahs”.

A masjid with unique features and fusion with local style

The Masjid was built between 1351-54 by Khan-i-Jahan Junan Shah, the prime minister of Feroz Shah Tughlaq, the third ruler of the Tughlaq dynasty in Delhi. Feroz Shah is known for his keen interest in architecture, especially mosques, and his patronage of several building and conservation projects. In his autobiography Futuhat-i-Firozshahi, he writes, “Among the many gifts which God bestowed upon me, his humble servant, was a desire to erect public buildings. So, I built many mosques and colleges and monasteries”.

The Khirki Masjid, which happens to be one of seven mosques built by Junan Shah, exhibits some unique features and architectural achievements of its time. Most prominent among them is its covered square plan as opposed to the typical open courtyard congregational mosque, and the fusion of local elements such as “jali” style windows with mosque architecture.

Moreover, because of the constant threat of Mongol invasion, almost all structures of that period, including mosques, had a military character such as tapering walls and turrets surmounted by crenellated parapets. The result is a unique mosque that looks like a fortress, or qila.

Also read: The Strange Tales of the Khirki Mosque

As a 15-year-old I spent all my pocket money googling Khirki Qila at a dingy internet café that had opened around that time in our area. Since my history books barely mentioned anything about the history of my village and its monument, I started looking for answers on the internet. I could not have imagined then that my interest in separating fact from fiction in the stories I heard from the elders of my community would lead me to an oral history archiving project

a decade later -- focusing on the very Masjid that had been a constant backdrop to my childhood and an object of google search but was now a subject of my research about its significance and what it meant to the people living around it.

It is through the interaction of the local community with monuments like Khirki Masjid that memories of a heritage site emerge. Photo: Ekta Chauhan.

Now I have the words to articulate why the very mention of the Khirki Masjid would always elicit different ideas, emotions and memories in different people. Making meaning of a heritage site is a long, gradual and contested process, and heritage monuments are much more than just their structures. Meanings and memories of a heritage site emerge through the local community’s interaction with it. It forms part of the everyday life and identity of the community that surrounds it, and, in this case, an entire village is named after the structure – Khirki Village. For that reason, the official and academic definition of a heritage site may very well differ from its local definition.

The Khirki Masjid has stood in its place for over six centuries and witnessed a long history, but arguably never as complicated as the juncture it faces now. At a time when the past has become a contested terrain, heritage monuments have become fodder for identity-based issues. This is reflected not only in political and administrative conflicts around the status of the structure but in the everyday lives of the people of Khirki as well.

Memories of the Masjid as a shared, safe place

The monument’s living memory is that of an abandoned site, surrounded by mystery. No one from the vicinity has seen or heard of the structure being used for its original purpose, that is, prayers. The earliest stories of the Masjid I heard came from some of the oldest inhabitants of Khirki village. Ajit Chauhan, 77, remembers the monument as a safe space for children to play during Delhi’s sweltering summer afternoons, which later became a sanctuary for people caught in the frenzied crossfire of Partition violence in 1947.

Several of his generation recall how women and children stayed inside the Masjid for days while the men kept guard against attacks. According to some villagers like Nathu Singh Kaushik, 84, there were apprehensions about an attack on the Hindus of Khirki village by a Muslim mob from nearby villages, due to which people hid inside the Khirki Masjid. For days,the Muslims of Khirki Village stood guard outside, declaring that anyone who attacked their “Hindu brothers” would have to face them first.

The octogenarian also remembers the happenings connected with the Masjid in the immediate aftermath of Partition. As the local Muslims fled their homes – in Khirki they comprised almost a fourth of the population -and Delhi struggled to keep up with wave upon wave of refugees from Pakistan, the government decided to accommodate some of them inside the Masjid on a temporary basis.

This, however, was unacceptable to the locals (all Hindus), who saw the monument as a mark of their identity and feared encroachment by ‘outsiders’. By taking this stance, some among them were also acting as guardians on behalf of their Muslim neighbours and friends who had left them in charge of their belongings and property. They still live in the hope that their friends might return and claim what is rightfully theirs, including the Masjid.

An air of mystery: inside the Khirki Masjid. Photo: Ekta Chauhan

The matter was finally brought to the attention of Prime Minister Nehru who swiftly resolved the issue – the refugees were settled around the Masjid and not inside it. It is hard to imagine that time now – how an abandoned monument served multi-cultural functions. A playground for children, an identity symbol for the members of a local community drawn from more than one religion, a shelter for victims of Partition violence, and finally as a place of prayer awaiting the return of the congregation.

At a time when the emphasis of the overarching political narrative in the country is on polarising society, the monument stands tall, bearing witness to a more diverse and inclusive past in living memory, when its identity was not described in binary terms of being either a secular or a religious structure.

Protected as a heritage site, fenced off from real life

But following the partition of the country, the rupture in Khirki’s community proved to be permanent. As the monument was taken over by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and brought under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR) of 1958, it was “sanitised”. Khirki Masjid was fenced off and an iron gate was installed at the entry. The accent was on conservation efforts and regulation of the monument, but in the process, the monument lost its living heritage component. The separation of the private space of an individual’s home from her/his community heritage was complete.

In the following decades, Delhi was sought to be developed as a modern city and urban villages like Khirki also saw sweeping changes. Their agricultural land was acquired by the state, electricity and water connections were laid out, a new bus stand came up on the main road, hospitals and schools were constructed. The fast-paced life of the city took over Khirki’s rather lethargic and relaxed way of life, and its once-beloved Masjid, fenced off from real life, receded into the background.

As the Masjid became more remote, cut off from the community’s life, a different set of stories emerged around it. It now became the setting for nightly ghost stories told by grandparents to scare off their little ones from venturing around the structure. Actually, the place was taken over by those who preferred to be in high spirits all the time, or itinerants.

In addition, the haphazard march of urbanisation combined with the administrative jargon that grew around heritage structures, also made the people of Khirki view the Masjid as an albatross around their necks. For every minor addition to one’s house or new construction, locals had to satisfy the rules of multiple agencies, and this naturally led to bureaucratic corruption and a nexus with the land mafia. The mental distance between the monument and its people continued to grow, and those who had lived around the Masjid for generations before these laws took effect, found it hard to comprehend what was happening.

Bureaucratic corruption and nexus with the land mafia made it difficult for Khirki’s inhabitants to go in for construction or renovation. It lead to a growing mental distance between the monument and the community. Photo: Ekta Chauhan

A theory of origin: ‘palace or durbar of Hindu king!’

In the past few years, the controversy around the “true nature” of the structure has gathered momentum. What started as harmless theories owing to the unique architecture of the structure have now turned into arguments to prove that it was a palace or a durbar of a Hindu king rather than a Masjid. It is variously attributed to Maharana Pratap, Prithiviraj Chauhan or even a certain fictional king, Kharak Singh but never to the Tughlaqs. An increasing number of locals have their own reasoning to buttress their point of view: “Have you ever seen a mosque without a courtyard to pray,” or “Clearly, the turrets are there to protect the king inside!”. Ironically, Junan Shah created a mosque with unique features such as a domed roof, a three-storey plan and turrets to show his skills.

Also read: The Changing Face of Delhi: Redesigned and Redefined Through the Ages

There have been multiple incidents of vandalism of the ASI board where the word “Masjid” was scratched over. The signage on the Trilok Chand Sharma Road outside the village and opposite Select City Walk mall now reads Khirki Qila and not Khirki Masjid. The simmering tensions between the Hindus of Khirki village and Muslims from nearby areas came to the surface in 2015. Following a video which went viral, asking Muslims to “reclaim” the mosque, there was an attempt by a group of individuals to forcefully enter the premises and offer prayers. As per ASI rules, no prayers can be offered inside a protected (‘dead’) monument.

Tensions ran high for a week, with men of the village planning to take matters into their own hands and guard the “prestige” of their village. The police soon arrived on the scene and a confrontation was averted. Since then, a rather precarious peace exists between the two communities in neighbouring urban villages.

In the war over the “original” nature of the monument, the biggest loss has been that of a shared ethos and community life. What was once a lively space has now been reduced to a site of contestation. While the older generation embraced the monument as an extension of their private space, regardless of its nature, the present generation is more interested in trying to establish the “original” builder and purpose of the structure than in forging a connect with it.

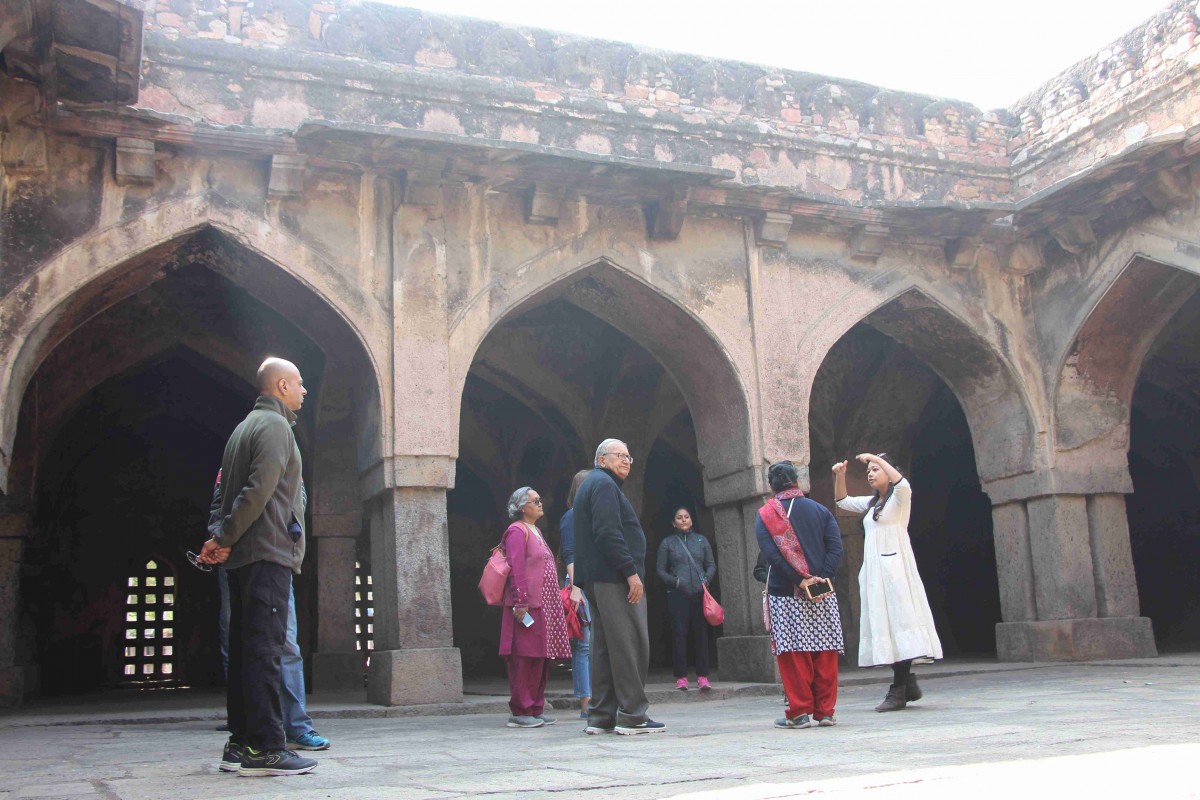

The author conducting a guided heritage walk to explore Khirki Village and its monuments. Photo: Ekta Chauhan

The monument hardly sees any tourists and it would be safe to say that the majority of youngsters in the village have not even set foot inside the monument. When I started taking guided heritage tours in and around the Khirki Masjid in 2018, while I got an overwhelming response in the form of bookings through social media, I am yet to get a single booking from the locals. Why locals, I have not been able to convince my cousins to visit the monument with me – not even when I threw in the lure of some interesting Instagram pictures!

Khirki Masjid’s magnificent arches and windows (khirki) now present a melancholy story of neglect and apathy towards our rich heritage of syncretic culture and co-existence. As per the latest reports, there are attempts by the ASI to restore the monument, but it would perhaps take longer to bring back to life the echoing halls of the Khirki Masjid, reinstate it in our lives as a living and harmonious space.

Ekta Chauhan is pursuing her PhD in heritage studies and researches at the intersection of heritage and communities. She runs an oral history archival project titled Dilli ki Khirki along with The Citizens' Archive of India, to record the personal histories of residents of Khirki Village, New Delhi.

This article went live on September nineteenth, two thousand twenty, at forty-four minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.