In India’s kaleidoscopic cultural history, popular forms of performative arts for entertainment have continued to provide a reflection of our diverse social landscape.

Countless art and traditional craft forms pushed boundaries of creative expression across generations; while some forms stood the tide of time, others were washed away.

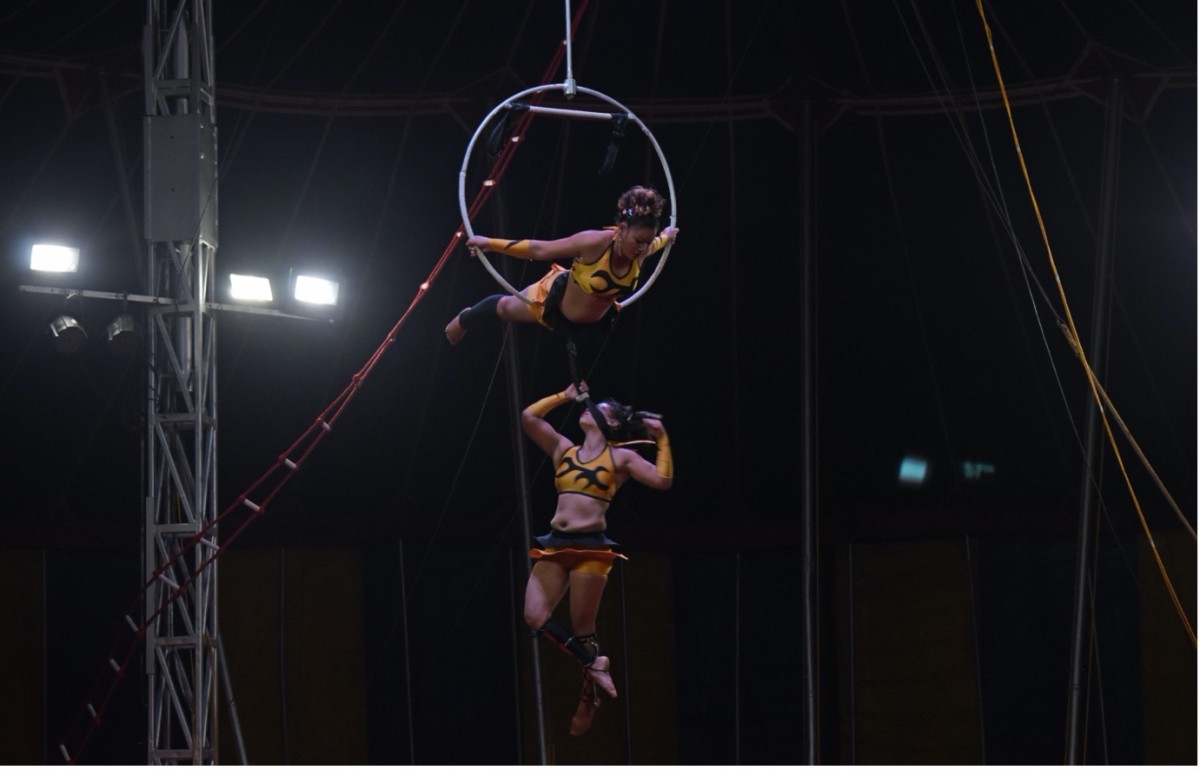

The circus, as one of the expressive forms that stood out, long before digital media and smartphones engulfed our children’s attention, was nothing less than a carnival of amusement.

In a recent field study undertaken by the Centre for New Economics Studies’ Visual Storyboard team, we spoke to and interacted with numerous artists of the circus near Maharashtra’s Pune.

The circus industry has a long history in India, dating back to the late 18th century. On March 20, 1880, the first Indian circus, named “The Great Indian Circus,” was held. Its creator, Vishnupant Chatre, travelled across India with his circus, establishing a number of circus schools that became training grounds for gymnasts and martial artists. This sparked the emergence of circus-led performance platforms that we know today as the Great Rayman Circus, the Whiteway Circus, the Eastern Circus, the Oriental Circus, the Rambo Circus and the Great Bombay Circus.

Up until a few years ago, each of these were regarded as some of the most popular and cherished forms of popular entertainment for the masses. The cheaper entry tickets also made the circus a more universalising, accessible platform for people from all communities to participate – both as performers and audience.

The sprawling grounds used to be jam-packed every time a circus would be set up. As part of their day’s performances, brightly dressed artists, clowns, gymnasts and shooters would take turns performing.

Notwithstanding the craze for the circus seen in the past, in recent decades, the circus industry in India (and for much of the world) is on the verge of extinction. The endangering of the expressive craft has resulted from a mixed of effect of digitally-enabled entertainment forms and some legislative reforms (adversely affecting the participation of animals and children in circuses). The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown made things worse for the circus community, rendering many artists jobless.

As Sujit Dilip, the owner of Rambo Circus, told our team:

“The circus display use to look like a replica of Animal Kingdom, but its industry was badly harmed when the government outlawed the ‘usage of wild animals’ in circuses. Another aspect that inhibited our performance and growth was the restriction imposed on working employees’ ages. The government did not allow any employees under the age of 18 to perform. You must have watched films where ‘child artists’ perform often in lead roles, why can’t they be allowed to perform a part in circus performances too?

Circus-acts need extensive training, and those interested in learning the skill were taught from an early age. However, when the government issued these new regulations, many trained youngsters-kids were no longer permitted to perform. For worse, most of these kids working with had to eventually go back to their native villages and could not contribute to their household incomes. Some work today as rickshaw-pullers or street vendors.”

Rajeev Chatterjee, a performer who plays the act of a joker in Rambo Circus, said:

“When children, as young as infants, are adored in films, why are they banned from working in a circus? This is an art form that take performative skills to another level, much like gymnastics. In a three-hour, pre-shot featured film, artists depend on the acts and stunts they perform, that too with multiple trials and camera tricks. In circuses, on the other hand, the two-hour show put up by artists includes live acts perfected by years of practice.

Artists take pride in the fact that everything presented on the stage is part of a live-living performance. The risks are our own. We fall, bleed, and stand back up again in front of their audience and we all do it for the overwhelming response that audiences give us. The government should support us and not make it more difficult for us to perform.”

The state of being for most artists our team spoke to was abysmal. Many performers live in temporary tents with no modern amenities and practice in poor infrastructural settings, while being away from home and separated from their families and children. There is no compensation provided to those who might injure themselves while performing riskier acts.

Apart from the ban on ‘animals and minors’, the government hasn’t extended any help to support and sustain the circus-ecosystem. Large, empty locations are becoming increasingly common. Owing to the weakening demand, private landlords – who give circus artists accommodation – impose exorbitant rents.

“Earlier we had a staff of 300-400 people, then slowly audience stop showing much interest, and that resulted in a decrease in the number of people working for circus. We had almost 150 people working for us (before the pandemic) till we stopped,” said Dilip.

The red tape around the process of getting a circus permit does not make it any easier. Circuses enjoy no subsidy or policy support, and above all this GST is levied on the minimum ticket price. During the pandemic, a number of circuses closed due to lack of financial support. Community-enabled support to Dilip and his team at Rambo Circus allowed them to perform through fundraising and donations. They even did some virtual performances, but none of this helped in reviving the business.

Moreover, as Dilip said, “It is difficult to find artists now. Most of those working with Rambo circus have been there with us for a long time. But, because of the restrictions and a weakening demand for circuses, most young people do not find any interest in joining us. This is sad.”

This study was undertaken as part of a CNES Visual Storyboard Initiative. Please check the original Photo Essay here and Video Essays here.

Deepanshu Mohan is associate professor of Economics and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), Jindal School of Liberal Arts, OP Jindal Global University. Jignesh Mistry is a senior research analyst and the Visual Storyboard team lead with CNES. Tavleen Kaur is research assistant, and Mohd. Rameez Raza is research analyst, with CNES.

We would also like to thank Ruhi Nadkarni, Ada Nagar, and Rajan Mishra for their assistance on editing-archiving the Photo & Video Essays from this Visual Storyboard.

The authors would like to sincerely acknowledge and thank Sujit Dilip, the owner of Rambo Cricus, Rajeev Chatterjee and other amazing artists from the circus community, for their invaluable help, support and guidance in making this field study possible.

All photos by Jignesh Mistry.