'It is Not a City, but a Dream': The Legacy of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

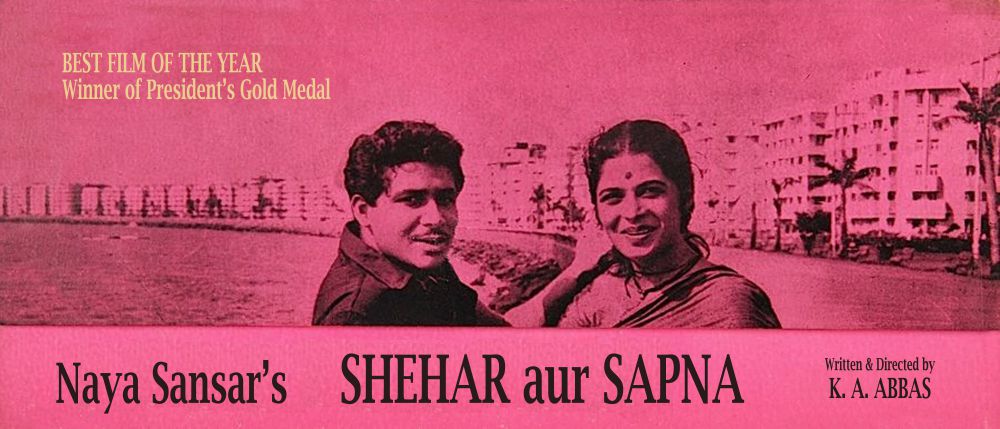

The 1964 National Film Award winner Shehar Aur Sapna, like many of Abbas's films, deals with contemporary realities in its exploration of Bombay and its dwellers.

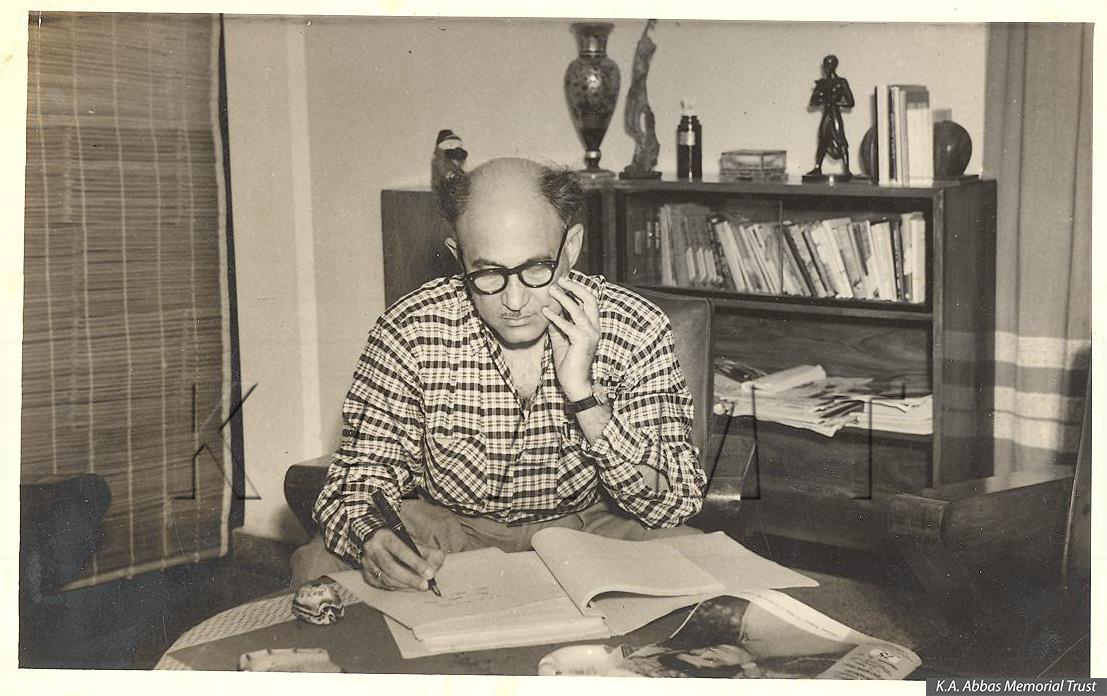

One of the special features of the 12th Habitat Film Festival held in Delhi (from May 19 to 28) was a specially curated package of five films written and directed by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas. Abbas, the David who faced the Goliaths of Bollywood and emerged the winner, was mostly forgotten by students and scholars of film studies until his birth centenary ushered in a renaissance of sorts.

During his life, of course, everyone wanted Abbas. The media wanted him because he wrote a column titled 'Last Page' nonstop for 43 years for Blitz and his documentary film Char Shaher Ek Kahani was instrumental in a landmark Bombay high court judgment on censorship. The world of Urdu wanted him for his 300 short stories including 'Ababeel', which was selected as one of the world’s hundred best. Progressive writers wanted him, the Indian People's Theatre Association wanted him; the list was long.

In this special segment showcased at the Habitat Centre, Abbas explores the city in myriad ways – physical, mental and figurative. Hindi cinema has always featured urban backdrops city but Abbas's engagement with the city – as a progressive writer and as a filmmaker – reflects his preoccupation with social and political issues. Whether it is the juxtaposition of harsh poverty with an increasingly consumerist ideology, the corrupting nature of the city, the claustrophobia and fear in the urban landscape, Abbas's films deal with hard contemporary realities.

In this regard, Shehar Aur Sapna is his most important film.

Eminent film critic Kobita Sarkar said about Abbas that he had a "love-hate relationship with the city of Bombay". This feeling resonates with us because he exposed the city at its worst and its best. Ironically, among the fascinating features of Bombay (in the pre-Mumbai era) that he loved was the Chor Bazar where old and secondhand goods are sold, some of which are stolen. That was always the first place Abbas would visit while preparing to produce a new film.

Abbas wrote of how the idea of Shehar Aur Sapna came to him. He was walking through Bombay’s Crawford Market one early monsoon morning hoping to catch a tram lumbering past, when he was stopped by sudden rain. Looking for shelter, he saw a couple taking refuge in drainpipes which were about one meter in diameter. "For years I had wondered where did the nearly one and a half million footpath-dwellers disappear in the monsoon season?," he wrote. Abbas crawled into the next drainpipe, which became his home for the next few hours. Brooding over the problem of homelessness while sitting in the mouth of a drainpipe he had a brainwave. He wrote, “In a flash, or rather a flash of lightning, the idea of a film story was revealed to me, the story of Shehar Aur Sapna.”

The story he conceived was of a boy from Haryana who arrives in Bombay to seek his living, and a Marathi girl who leaves home after she finds her father mortgaging his house to pay for her dowry. The boy and girl meet in a rainstorm, in a drainpipe like the one Abbas sat in. Other details and other characters began to take shape in his mind. He called it shikwah at first. It was man’s shikwah (protest) to God, inspired by Allama Iqbal’s epic poem of the same name.

He narrated his plot to his wife Mujji who was critically ill. It was on her suggestion that he created four old men of the basti; the mad poet (Manmohan Krishna), the wrestler (David Abraham), the stage actor (Anwar Husain) and the veteran violinist (Nana Palsikar). But before the screenplay was ready she was no more. Abbas wrote, “She was no more in the city of the living. But the dream persisted”. This, Abbas writes, was her legacy.

As often happened with his films, Abbas first tried the plot as a short story or novella. One Thousand Nights on a Bed of Stones was first serialised in Blitz. Then with or without his permission, it was translated and published in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi and Malayalam. The book found its way to the Soviet Union; there it was called Tysacha Nahaj na Kamennem. When he went to Moscow, his friend Vera Bikova, the translator of the story, gave him a copy.

The Soviet film director, Mikhail Kalatozov (director of The Cranes Are Flying) asked him if the story would be the basis of his next screenplay, without thinking twice, Abbas said, “Yes” but on second thought he wrote, “In the realm of commercial filmmaking in India, what is the opinion of two directors worth against such established facts as the producer’s past record as a flop filmmaker!”

He wrote the screenplay in Moscow. On his return, he read it out to the members of his Naya Sansar unit and they all said 'yes'. There was only one slight hitch – he had no money. So he approached the Film Finance Corporation for the princely sum of one and a half lakh rupees.

Meanwhile, he was on the lookout for two young actors – the boy must look like a Jat from Haryana, he felt, rough and unsophisticated, and the girl must look a Maharashtrian whom the cruel and heartless city turns into a desperate knife-wielding wench. He chose his friend Jairaj's son Dilip Raj and Surekha Parkar for the lead couple.

Interestingly, Dharmendra who was seeking work knocked on his door for a role in his new film. He told Dharmendra that he could not disappoint Dilip. Dharmendra said, “Remember, Mr Abbas, one day I will work in your picture.” Later Abbas wrote a story of a ragpicker in a city, which was a tailor-made role for Dharmendra – but it was not box office material. He turned down the offer. The story later appeared as 'Teen Pahiye, Ek Purana Tub Aur Duniya Bhar Ka Kachra.'

Meanwhile, the hero and heroine, breaking the tradition of usual heroes and heroines, did not mind coming from their homes by bus to Juhu, just like students going to college, with their notebooks under their arms. To acclimatise them to living and working under the restricted space of a drainpipe, he told them to rehearse their scenes under his office table.

From the royalty received from the Gramophone Company and some publishers Abbas raised Rs 20,000. With that sum, they were able to complete four edited reels and they showed it to the Film Finance Corporation (FCC).

Abbas waited and waited for the FFC's decision, doing whatever shooting he could till his resources were completely exhausted. No further shooting was possible. In March 1961, the FFC informed him that his application had been rejected.

In February 1963, when Satyajit Ray was in Bombay, Abbas showed him the few reels that he had shot. Ray said, “The story is the story of Pather Panchali all over again. All that you need is a little bit of money which I am sure you could easily raise.” That encouragement changed the destiny of the film. The very next day, Abbas secured a loan of Rs 50,000 for raw stock. Then he wrote 22 letters to as many friends, explaining his difficulties about his film and asking for loans of anything between Rs 500 and Rs 25,000. In a week, cheques and money orders started coming in from friends like Ramesh Sanghvi, Rajni Patel, Mulk Raj Anand, R. K. Karanjia, A.S.R. Chari etc. The total came close to Rs 5,000. But the greatest contribution was from 15 members of the unit – nine technicians and six artistes – who all said that they would not expect any money till the firm was completed and sold. So Abbas proposed to make them all equal partners in the profits, if any.

There was no song in the film but a poem of Sardar Jafri sung by Manmohan Krishna, who played the mad poet, the Greek chorus of the film. The whole rendering took exactly one hour.

Abbas had kept the climax of the basti of hutments being demolished by the developer’s bulldozer. At the site of a real basti they built additional huts, which would be demolished by the bulldozer. The bulldozer began to systematically demolish the huts. Thinking they were the police, the residents stood with sullen and angry faces showering curses, until the sequence was explained to them. The last scene was at Bhola’s hut, all that remained of the basti. Here Radha was delivering her firstborn. The four self-appointed guardians of Bhola and Radha stood before the bulldozer.

“Get out of the way,” said the bulldozer driver.

“We shall not budge. Don’t you know what is happening inside?”

“What?” asked the driver contemptuously.

Husain, the old actor, shouted, “A human being is being born”

And just then from inside the hut, the first cry of the newborn baby was heard. "The forces of life had triumphed over the forces of evil, the legions of the tycoons had been vanquished by the people who were no longer afraid of them. And spontaneously the basti people broke into cheers."

When Abbas edited the film he began the process of demolition with the words of the mad poet, Diwana: “Woh aa rahe hain, Woh aa rahe hain." – They are coming, they are coming. Throwing realism overboard he took advantage of the mad poet’s vision who saw in the single bulldozer a whole Nazi Panzer division. Abbas intercut the shot of the bulldozer demolishing the huts with shots of Nazi tanks crushing masses of people. The sound of the bulldozer crushing the bamboo of the huts was eerily like the sound of human bones being crushed.

In one week, they were back for a day in a studio where they built a drum-shaped house, very artistically furnished, with a picturesque Kathiawari paalna, also a double bed with two embroidered pillows. The simple Radha, looks around in awe, puts her baby in the paalna and asks, “What city can this be?” And Bhola replies, “This is no city – only the dream! Yeh shehar naheen – sapna hai!”

The frame froze and over it appeared the last title which conventionally should have been “The End” but which was changed to the more optimistic “The Beginning” which Abbas did in every one of his pictures.

In an effort to persuade some distributors to buy the film, they arranged a record number of 47 screenings over a period of six months. Meanwhile, they entered the film in the the national film awards. Six films were selected and Shehar Aur Sapna was the sixth. It was a late April evening when Abbas got a telephone from Delhi and learnt that his film had won the president's gold medal. “And so, that night," he wrote later, "there was no sleep for the fifteen!"

Around this time Abbas heard that Nehru was not well so he sought his permission to bring the unit to him before the award function. Abbas had already done his homework about the equal division of Rs 25,000 between the 15 of them, which he requested Nehru to give away. While giving the purse to Surekha, he looked at the cheque and said, "I hope Abbas has not committed any arithmetical mistake in dividing the indivisible amount into 15 shares.” Then he asked, “Isn’t there a song in the film?” Abbas said, “There is a poem,” and introduced the poet Jafri, and Krishna, the singer. Panditji asked Krishna, who chose a piece tragically appropriate for the occasion, especially its last lines:

Woh jo kho jaen to kho jaayegi duniya saari

Woh jo mil jaen to saath apne zamana hoga(If they get lost, it will be as if the world itself is lost

If they are found, then the times are ours)

There were tears in the singer’s eyes as he recited and everyone present was deeply moved for they knew that it would be their last glimpse of Nehru.

In the making of his films, whether the subject is on pavement dwellers, ragpickers, the downtrodden, the homeless, Abbas first exposed himself to that condition and tried to think like them, live like them, thereby understanding their desperation, their psyche. Why was this so important to Abbas? What was he trying to communicate to people by exposing their condition? What did Abbas hope for?

His own words on Shehar Aur Sapna are the best explication of what he wanted to communicate through his films: "Some people say I am mulish in trying out themes of social realism, without compromise. 'Give the people what they want,' they advise. But I believe in doing what satisfies not only my personal ego but my social conscience. I have no martyr complex. I have enjoyed making each one of my films."

This article went live on May twenty-seventh, two thousand seventeen, at zero minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.