Omer Aijazi’s ‘Atmospheric Violence’: A Sincere Take on Life in the Fragile Borderlands of Kashmir

Last month, India and Pakistan came to the brink of a war in the aftermath of a terrorist attack in Pahalgam that led to the killing of 26 civilians.

As expected, the events have brought the Kashmir issue back to the centre stage, with both countries pressing their rival claims over the parts of territories beyond their contested borders with renewed gusto.

On May 29, Union defence minister Rajnath Singh reiterated these claims when he called the people of Jammu and Kashmir across the Lin of Control as one of “our own”, adding that he expected them to return to India one day “voluntarily.”

Given the charged nature of discourse in India, edged always with hyper-patriotism when it comes to Kashmir, few Indians would be willing to go beyond the cliches about the region repeated ad nauseam by politicians and the media.

It is also least expected of them to engage seriously, and perhaps with a dash of academic interest, into the lives of people 'on the other side' without letting their biases cloud their perspectives.

The LoC sits astride the long sweep of mountain ridges fenced with lines of concertina wires that zip like a suture through meadows, forests, ravines and alpine lakes.

Such an unnatural division of shared geography was bound to create challenges that have survived generations and continue to rumble violently in the lives across both sides of the de facto border.

Long time ago, when I was working as an intern with a local weekly in Srinagar, I took up an assignment about the LoC’s impact on local wildlife, and realised how enormous was the magnitude of pain inflicted by this man-made division on, let’s say, leopards as they scoured for food, sniffing their way towards their prey only to find themselves walled off by the LoC, its high-tensile steel mesh glistening against the sun. I could only imagine what it did to humans inhabiting this land and who considered it sacred.

Later, my understanding of the LoC, and its trouble-stricken history, was supplemented by serious readings such as Shahla Hussain’s Kashmir in The Aftermath of Partition.

Citing rich archival material, such as the fictional short story, 'The Neutral Zone', written in the 1960s in which Kashmiri villagers defy the demarcations one night and secretly cross over the other side, Hussain’s writing unsettles the nationalistic framings through which India and Pakistan have viewed the people living in the territories under their respective control.

Poignantly written, her work was vital in the sense that it sought to restore political agency to Kashmiris.

Of course, the more I read, the more curious I got. It left me grappling with a lot of questions that remained unanswered, especially regarding how people across the other side of this dividing line see and experience the world around them.

An exemplary anthropological study

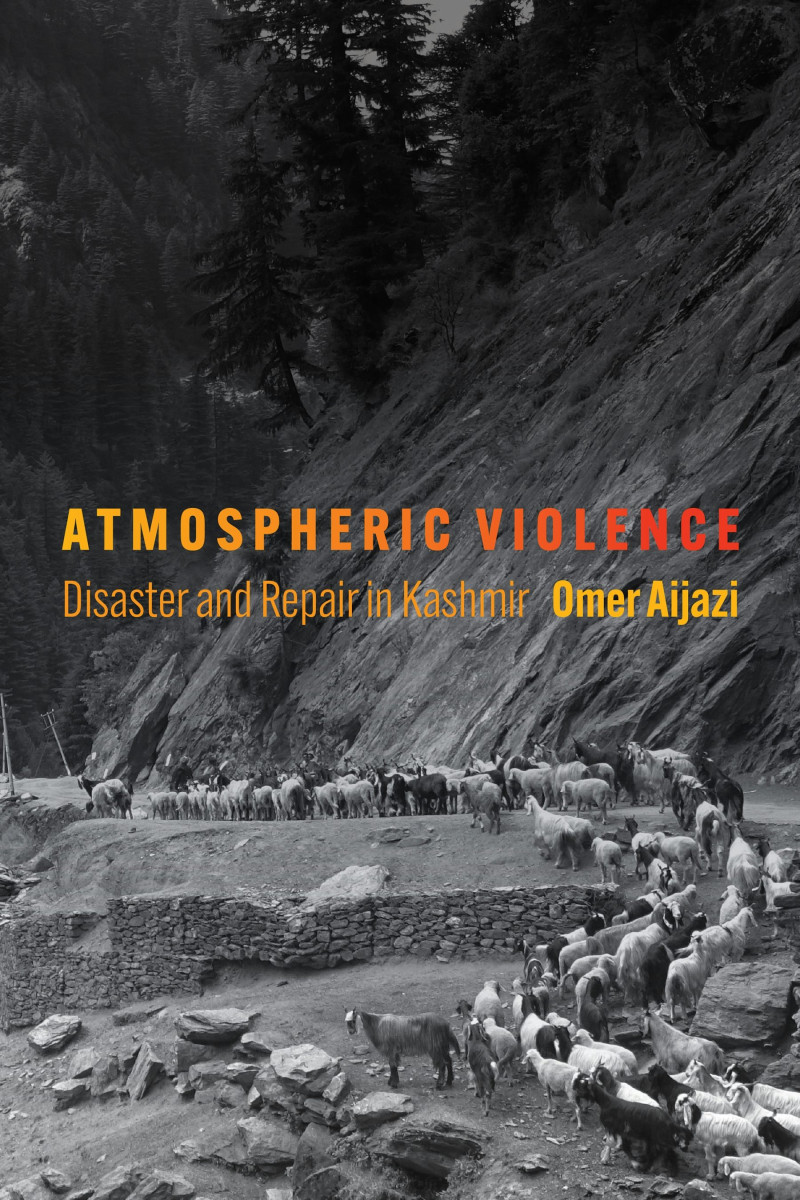

It is on this count that Omer Aijazi’s new book Atmospheric Violence: Disaster and Repair in Kashmir fares exceptionally well. The book builds on the author's extensive travels across the mountainous region and his conversations with the people living in the pahars (mountainscapes), as the topography is colloquially called.

Omer Aijazi, Atmospheric Violence: Disaster and Repair in Kashmir. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2025.

The result is stunning ethnographic work that illuminates the fundamentals of life in the pahars of Kashmir under Pakistani control in a fresh light.

Omer’s stories unspool through elaborate encounters with his subjects, called ‘scenes’, with each scene constituting a broader canvas onto which the lives of its protagonist is projected.

It is through scenes that we discover that the survival of the inhabitants of this region — called 'Azad Jammu Kashmir' by the Pakistanis and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, or PoK, in India – is so deeply enmeshed with the pahars that they render the modern logics of the nation-states as irrelevant. As one Lateef, a villager on the border with Northern Pakistan and PoK tells him, “What is the difference between us [in northern Pakistan] and those in Kashmir? Nothing! My forefathers migrated to these pahars to escape the zalim (cruel) Dogra rulers. But this doesn’t mean I am not Kashmiri.”

As Omer profoundly observes, “The pahars provide openings to circumvent the normative truths of the nation-state as the only valid complement to life and politics. They bring into view the pahari people’s daily struggles for political self-designation,” by which the author means – among many things – their dissatisfaction towards the Pakistani establishment.

As Omer’s conversations with the locals reveal, Kashmiris in the areas under Pakistani control deeply resent the checkpoints dotting the vast swathes of the pahars; swear at mainland Pakistanis for urinating openly in the mountains, or for bringing prostitution in their midst.

When he asks Shehzad, his local research assistant, of what locals believe is the origin of Kashmir, he replies with a story of Prophet Solomon mounted on a winged horse who descends from the skies, and encourages his djinn Kashf to marry a local fairy, Mir. This is how the region got its name. The anecdote reflects how, even on the other side of the LoC, Kashmiris locate their provenance in the foundational myths that only reaffirm their status as a standalone people, resisting their “current geopolitical emplotment.”

Living amidst myriad threats

But such a posturing can also come at a cost. As Omer writes, “Kashmiris in Pakistan are under constant surveillance…and...for the reasons of self-preservation they must actively demonstrate allegiance to Pakistan,” failing which they, “risk interrogation, extrajudicial imprisonment, or worse – disappearance.”

On the Pakistani side, all forms of life unfold under the suspecting shadow of the army. “It regulates most institutions and services, from hospitals to the only mobile phone service in the pahars,” Omer writes.

Elsewhere in the narration, we are introduced to Abrar, a local tourist guide, who is harassed by the Pakistani police in Lahore because of his Kashmiri identity. Kashmiris are called by the expletive ‘pancho’ and suspected to be disloyal.

Omer’s narration is pervaded by general observations about the region that offer us fascinating insights into the daily travails that residents in areas under Pak control must navigate. They include bad quality roads; the mudslides along the border that push landmines from the Indian side into their midst, blasting away their livestock; the restrictions on the mobility, on fishing in the rivers, as well as on collecting high-value medicinal plants. All this reminds us of what living in a highly-militarised terrain at the confluence of two perpetually feuding nuclear armed rivals means.

Quoting Sara Shneiderman, Omer wonders if the nations of India and Pakistan would be capable of fostering alternative citizenship categories for “border residents in response to demands and practices from below in non-post colonial trajectories of state formation.”

Scenes tell profound stories

A ‘scene’ in his narration opens about a person named Niyaz, who suffers from a disability. His case simply illustrates the difficulty of studying – where students submit work and access study material through postal systems. Since his case – like much of the book – is also foregrounded against the 2005 earthquake, it also serves to illustrate how the inbound stream of foreign aid in the aftermath of disaster reconfigured the economic and social milieu in the 'AJK' region.

By creating new avenues of exploitation, the aid flow disrupted the older modes of living, creating new pressures and challenges for people like Niyaz. For example, we learn how unequal distribution of aid money engendered social schisms that did not previously exist. Niyaz finds himself on the receiving end of these new forms of inequalities.

The new housing schemes announced after the earthquake, too, went to radically transform the family structures in the region, with large families atomising into single units, fraying the bonds on which the region’s social values were underpinned.

The disruptions caused by the quake have rippled across time and space and continue to warp the people’s lives and undermine their symbiotic relationship with the natural surroundings.

The ‘scene’ with Parveen, a midwife, highlights the toil of a woman as she struggles to get employed intothe local government. She donates her own private land for the construction of a local health unit where she later seeks contractual employment which is regularised only after 15 years of service.

The case of Sattar Shah struck me for a particular reason. Here is an old unmarried man, living all alone as a tenant farmer at the mercy of a local landlord. His austere lifestyle and his self-abnegation reminded me of the Reshi saints of yore of Kashmir. Shah subsists only on bread made from maize flour. As to any other necessity? He leaves that to Allah to arrange for him. The pattern in which he affirms his faith in the divine is so uncannily analogous to that of people in J&K.

The Kashmir that ‘progressives’ couldn’t see

While India’s liberal elite generally interprets the role of religious devotion in Kashmir through deeply reductionist terms, Omer, by contrast, offers a highly perceptive exegesis, anchoring it neatly into its complex backdrop. “Sattar Shah’s friendship with Allah is freedom from disappointments and letdowns of others. This entails freedom from the push and pull of others, as well as from the neoliberal ordering of humanitarian agencies, such as their mandatory housing designs and “resilient” homes.”

India’s intellectuals have long debated why religion permeates so obstinately through the lives of people in Kashmir. And worse still, why it remains the idiom of political expression for them. Omer’s sharp analysis of Sattar Shah’s relationship with God may answer why.

He writes, “taking sacred seriously” means to “shake the archives of secularism by understanding the spiritual as epistemological and not as a lapses outside of the bounds of rationality.” It is the work, he continues, “of repair, restoring what colonialism has fragmented and dismembered.”

Conscious of being a Pakistani citizen, Omer’s approach to Kashmir is prefaced with a caveat: “It would be a mistake to initiate any conversation on Kashmir without acknowledging the elephant in the room: colonial occupation,” he writes.

He is indebted to locals for always reminding him that he is not one of them. “Any solidarity I may offer is insufficient until I am prepared to engage in a radical repositioning and redistribution of the benefits and protections that I embody as a Pakistani citizen – readjustments perhaps I am not yet prepared to undertake,” he adds.

At times, his candour and scrupulous concern for ethics feels like a damning indictment of the ways many Indian journalists and academicians have approached Kashmir because it is quite rare that someone would write about this side of Kashmir with the same sincerity that Omer has written about thr Pakistani side.

He reminds the readers that the struggle to deliver Kashmir from these challenges lies not in the war bluster that two countries hurled at each other recently, but by marshalling the kind of imagination that recognises the Kashmiris as people entitled to live in a kind of Kashmir where they “can freely choose living, laughter and learning.”

Shakir Mir is an independent journalist based in Srinagar. His work is located at the intersection of conflict, politics, history and memory.

This article went live on June ninth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-one minutes past nine at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.