Sangh Parivar's Clash With Urdu: Don’t Want It But Can’t Speak Without It

On September 18, 2025, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB) issued a notice to Hindi media channels, instructing them not to use Urdu words in their shows.

The MIB issued this notice following a complaint filed on September 9, 2025, by a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) worker, S.K. Shrivastava, a resident of Thane (Maharashtra), on the Centralised Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS) portal. In his complaint, Shrivastava alleged that Hindi news channels like TV9 Bharatvarsh, Aaj Tak, ABP News, Zee News and TV18 were using nearly 30% Urdu vocabulary in their broadcasts.

The complainant further stated that although these channels claim to be Hindi news channels, they routinely use words from other languages in their daily coverage, which he described as ‘fraud’ against the public and a criminal act. He demanded that these channels be instructed to appoint certified Hindi language experts and to publish the expert’s certification on their respective websites.

Ironically, the five-line notice issued by MIB in response to the complaint itself used at least five Urdu-origin words: terms rooted in Arabic and Persian but now integrated into Hindi through Urdu. These included words like ‘Gaur’, ‘Galat’, ‘Istemaal’, ‘Khilaaf’, ‘Shikaayat’ and ‘Tahat’— all of which, in their current usage, are considered part of the shared Urdu-Hindi lexicon.

The first word, ‘Gaur’, is of Persian origin and in Hindi, corresponds to ‘Dhyan’ (attention) or ‘Soch-Vichar’ (contemplation).

The second word, ‘Galat’, comes from Arabic and has Hindi equivalents such as ‘Ashudh’ (impure), ‘Anuchit’ (inappropriate), ‘Asatya’ (falsehood), ‘Dosh’ (fault), ‘Truti’ (error), and ‘Pramad’ (mistake).

The third word, ‘Istemaal’, is also of Arabic origin, having entered Hindi through Urdu. It has now become firmly rooted in everyday usage. Hindi does have its own native word for it – ‘Prayog’ (use) – but ‘Istemaal’ is far more common in spoken language, while ‘Prayog’ tends to appear more in writing.

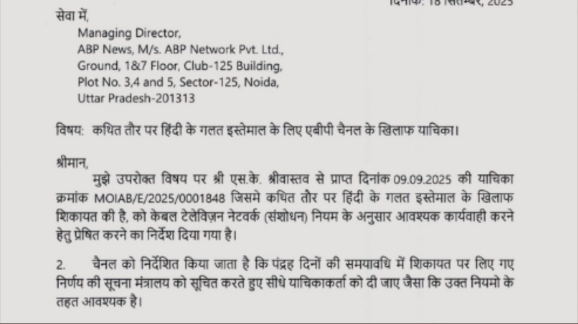

Screenshot of the letter by Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to one of the news channels. Photo: The Wire Hindi

The fourth word, ‘Khilaaf’, is of Persian origin and translates into Hindi as ‘Viruddh’, ‘Pratikool’, or ‘Ulta’ – words that convey opposition or being contrary. Sometimes, ‘Vipreet’ is also used in Hindi to express contrariness or adverseness. However, despite being available in the lexicon, these Hindi words are rarely used in common speech.

The fifth word, ‘Shikaayat’, is originally Persian and has been absorbed into both Hindi and Urdu under the influence of Arabic and Persian. In Hindi, it can be used to express ‘Asantosh’ (dissatisfaction), ‘Dukh’ (grief), or ‘Ulaahnaa’ (reproach). Its close synonyms include ‘Shikvaa’, ‘Gilaa’ and ‘Fariyaad’— all of which also trace their roots back to Arabic-Persian usage.

The sixth word, ‘Tahat’, is of Arabic origin. In Hindi, it means ‘Ke Niche’ (beneath) or ‘Ke Antargat’ (under the purview of). Grammatically, it is an Arabic preposition that denotes being below something or under someone's authority.

Also read: In 'Fact-Check', Govt Confirms Report of Notice to Hindi News Channels Over Use of Urdu Words

It is worth noting that the debate around the use of Urdu words in Hindi, or even the very existence of the Urdu language, is far from new. It dates back to the period when Scottish linguist John Gilchrist established Fort William College in Calcutta and formally separated the Nagari and Urdu scripts into distinct linguistic categories.

Later, with the transfer of power in 1947, Urdu came to be seen exclusively as the language of Muslims in India. As a result, Urdu gradually receded from the academic and institutional mainstream in post-British India. However, in everyday speech, Urdu vocabulary has continued to be widely used, much like it was in British India and earlier.

In fact, one could argue that in present times, the usage of Arabic-Persian-origin Urdu words in Hindi has only grown more pronounced.

In post-British India, the continued use of Urdu words in Hindi has sparked multiple controversies. These disputes even reached the courts, and in every instance, the verdict upheld Urdu’s rightful place, affirming that it is not the language of Muslims alone, but a language of Hindustan itself.

This very position was reiterated in the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment delivered on April 15, 2025. As with past instances, this case too was filed by individuals affiliated with the BJP, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and their associated organisations which form the Sangh Parivar (Family of Hindutva organisations).

It is indeed striking that the very Sangh Parivar, which so vehemently opposes the Urdu language and its vocabulary, relies heavily on Urdu words in nearly every statement, sentence and speech they deliver. In fact, it is impossible to escape this because many of these Urdu-derived words have no direct equivalents in modern spoken Hindi.

To illustrate this contradiction, let us look at a few slogans coined by the BJP and its leaders, as well as some of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s key speeches. Without the use of Urdu words, many of these slogans and speeches might never have taken shape, let alone achieved such widespread popularity in society.

Recall the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. During that campaign, the BJP and its prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi popularised the slogan: “Abki Baar, Modi Sarkaar.”

The word ‘Sarkaar’ in this slogan is originally Persian, which entered Hindi via Urdu. In Hindi, it can be loosely translated as ‘Shaasan’ (governance), ‘Prashaasan’ (administration), ‘Maalik’ (ruler), ‘Shaasak’ (governor) or ‘Mukhiya’ (leader). Due to the widespread use of Persian during the Mughal era, this term, along with many others, became embedded in Indian languages like Hindi and Urdu.

Now imagine removing ‘Sarkaar’ from the slogan “Ab ki Baar, Modi Sarkaar” on the grounds that it is a Persian-origin Urdu word. Could the BJP or its leaders and cadres who rail against Urdu, have even coined such a slogan? And if they had not, would they have achieved the historic feat of forming their first full-majority government at the Union? What about the second time, when their slogan was, “Fir Ek Baar, Modi Sarkaar”?

In the same 2014 campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi also began projecting himself as a “Chowkidar” – a watchman of the nation, guarding against corruption. He frequently said things like: “Main desh ka chowkidar hoon, main bhrashtachar nahi hone dunga. (I am the nation’s watchman; I will not allow corruption.)”

The word ‘Chowkidar’ in this slogan is itself a hybrid. The root ‘Chowki’ comes from Sanskrit, meaning “one who holds or guards a post.” But the suffix ‘-daar’ is of Persian origin, commonly used to denote someone who holds a position or responsibility.

Thus, ‘Chowkidar’ is a blended word, combining elements from both Sanskrit and Persian, and literally translates to “one who guards the chowki.” This illustrates how deeply interwoven Persian, and by extension Urdu, has become in the very vocabulary used by those who now seek to reject it.

Similarly, after winning the 2014 Lok Sabha elections and coming to power, Modi’s government undertook demonetisation. When assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh were held in 2017, Modi, while addressing a rally in Moradabad in 2016, delivered what would become one of the most popular lines of his political career.

Defending his government’s decision on demonetisation, he said: “Ham to faqir aadmi hain, jholaa uthaa kar chal padenge.” (We are just humble itinerants; we’ll pick up our bag and walk away.)

In this sentence:

- The word ‘Faqir’ is of Arabic origin, translating as “one who begs,” “a poor person” or “one who lives by alms.”

- The word ‘Aadmi’ is of Persian origin, derived from the Arabic ‘Aadam’, and means “human being” or “manushya/manav” in Hindi.

- The word ‘Jholaa’ is a vernacular word commonly used in Urdu, meaning “a cloth bag used to carry belongings.”

Beyond this, Modi – and other leaders of the Sangh Parivar – frequently use words like ‘Garib’ (poor), ‘Neend’ (sleep), ‘Elaan’ (announcement), ‘Khabar’ (news), ‘Haftaa’ (week), ‘Wajah’ (reason), ‘Be-wajah’ (without reason), ‘Mausam’ (weather), ‘Qimat’ (price), ‘Mulaaqaat’ (meeting) and ‘Umar’ (age) – all of which are of Arabic or Persian origin, and have entered Hindi primarily through Urdu.

Originally written in Hindi by Shahadat. Translated to English by Akshat.

Shahadat is a writer and translator. He has published two collections of short stories, 'Aadha Safar Ka Humsafar' and 'Curfew Ki Raat.' He is currently working on his first novel: 'The Last Hindu House in the Neighborhood.'

This article went live on October twentieth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.