Nayagram: Come winter, Nayagram, a small village in the Paschim Medinipur district of West Bengal, transforms into an open-air gallery. Every house becomes an artwork that narrates Bengal’s rich history, mythology, and culture. In this village, every resident is an artist, carrying the honorary title of chitrakar/patua (painter).

Patachitra is a traditional form of Indian scroll painting, often depicting Hindu mythological stories. The artists of Nayagram have been creating these scrolls for centuries, narrating tales of gods and goddesses narrated with songs and music written by them.

Over 130 families of artists here live a unique dual identity – they paint vivid tales of Hindu deities, recite their stories in song, and at the same time, follow Islamic faith. Many of them consider themselves to be descendants of Vishwakarma, the divine architect of Hindu mythology.

A woman painting Patachitra art in Nayagram, West Bengal. Photo: Joydeep Sarkar

Shamsuddin Khan goes by the name of Khadu Patua. His family migrated from erstwhile East Pakistan to this village during the Bengal famine. The family has been involved in Patachitra art for generations, earning a living by showcasing their paintings and songs.

He says, “Back then, showing scrolls and singing their stories at people’s homes was our livelihood. Despite religious differences, we were treated with respect. From a life of begging, we now live with dignity, practicing both religions.”

Patachitra is distinguished by its fabric-lined back, giving the scrolls a rolled shape for easy transport and preservation, a legacy of its roots with traveling artists. These scrolls feature vertically arranged images, typically 10-to-20-feet-long, depending on the story. Yet, over centuries, the art form has retained its core artistic and narrative traditions.

A man painting Patachitra art in Nayagram, West Bengal. Photo: Amit Kumar Maity

“This is a tradition passed down through our generations. Our ancestors started this, and we are continuing it. Our forefathers told us stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Devi Mansa’s legends. We remember these tales and illustrate them as sequential events in our scrolls,” says local artist Ajay Chitrakar.

Patachitra artists use traditional methods, utilising locally sourced materials such as leaves, vegetables, stones and flowers to create a vibrant palette of natural colours. This knowledge of colour making is meticulously passed down through generations.

“To make the colours, we gather raw materials like bael fruit for glue. Green comes from leaf extracts, yellow from raw turmeric, blue from blue pea flowers, white from ground rice paste, and red from Malabar spinach berries. These natural colours are used not just in scrolls but also in fabrics like sarees and shawls. We avoid chemical dyes entirely,” explains Saleha Bibi, whose family is involved in the craft.

Traditionally, ‘pater gaan’ (story songs) in Patachitra were primarily performed by men. While women are now taking on more prominent roles in this art form, in contrast, there has been a decline in interest among young men in learning the craft. Despite these shifts, the core of Patachitra – the meticulous crafting of scrolls using traditional techniques and natural dyes – is central to the identity of the artists.

Sole occupation

Recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) in West Bengal and subsequently awarded the Geographical Indication (GI) tag, Nayagram’s Patachitra has achieved global acclaim in recent times. Artists from this village are now invited to showcase their work in countries such as Japan, Australia, and Germany.

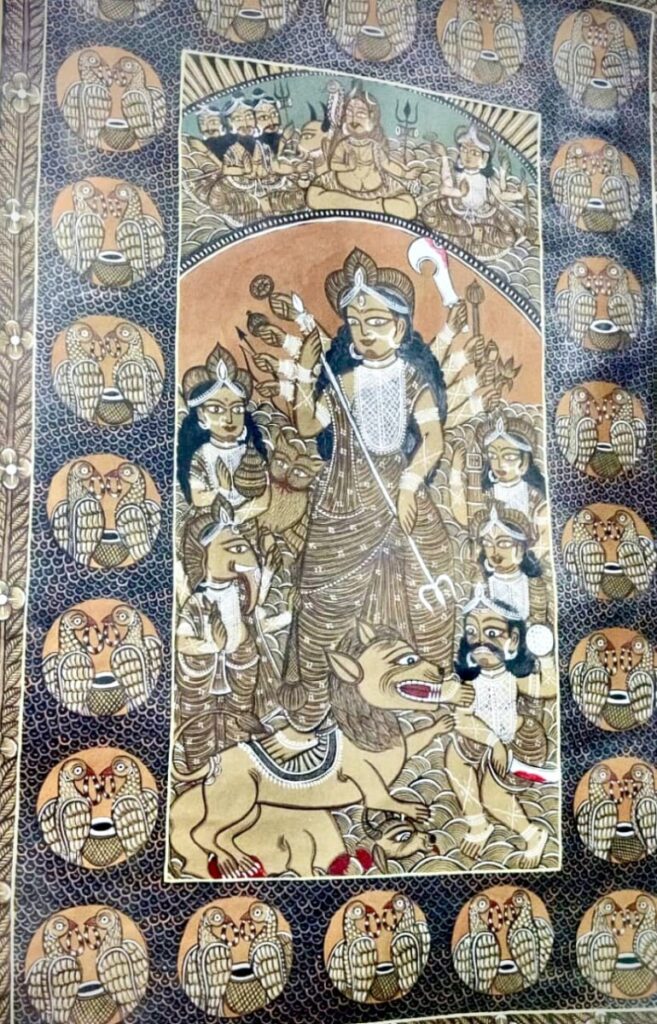

Hindu goddess Durga in Patachitra painting. Photo: Amit Kumar Maity

“People in foreign countries truly value art and pay accordingly. Last year, I earned Rs 1.5 lakh during an exhibition, which I used to build a house. My son funded the upper floor from his earnings in another country’s exhibition. This is how we sustain ourselves,” says Reifun Bibi, popularly known as Radha Chitrakar.

Nayagram, despite its growing popularity, remains a daytime destination with limited tourism infrastructure. The village still does not have a senior school. Most artisans have only received primary education. The nearest health centre is 5 kilometres away.

“Eighty houses in this village are home to 136 artisan families. Farming isn’t an option, so Patachitra is our sole livelihood. Men leave early each morning to perform and sell their art in nearby towns, while women work on new pieces at home. The government provides a monthly artist pension of Rs 1,000 but that is insufficient,” says Mantu Chitrakar, a spokesperson from the community.

A Durga-themed Patachitra scroll sells for Rs 6,000, while a painted kurti (Indian tunic) costs Rs 700. Lanterns, teacups, t-shirts and shawls adorned with Patachitra art have also grown in popularity.

After years of hiatus, Nayagram recently hosted a local Patachitra festival. The area transformed into a magical realm called ‘Pat Maya’ for three days when the chitrakars set up stalls and opened their homes.

“Art lovers from around the world appreciate and support us. It’s their love and the message of harmony that keep our craft alive,” says Ajay Chitrakar.

Translated from Bangla by Aparna Bhattacharya