Vincent Van Gogh: The Colourist of the Future

In Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, there is a whole gallery dedicated to the many letters that the artist had written to his family and friends, also some that he, in turn, had received from them. Many of these you can hear read to you – in Dutch, English or some other major European languages – if you plug in the device sitting next to the exhibit, click on the number shown, and switch on the recording. Of the many that I listened in to, the one that has stayed with me most vividly is Emile Bernard’s letter of August 2, 1890, to the young art critic Albert Aurier, giving the latter an account of Van Gogh’s death and burial.

“On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung, making a sort of halo for him.......The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, young dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favourite colour, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of as being in people’s hearts as well as in works of art.”

Bernard goes on to describe the last journey in the hearse, the cemetery, “... a small new cemetery strewn with new tombstones. It is on the little hill above the fields that were ripe for harvest under the wide blue sky that he would still have loved ... perhaps.” After that, as Van Gogh was lowered into the grave, “anyone would have started crying at that moment.... the day was made too much for him for one not to imagine that he was still alive and enjoying it...”

No mean painter himself, Bernard brought the artist’s insight into his tribute to his dear departed friend, capturing the essence of Vincent Van Gogh’s art, also of his life, in no more than one hundred words. The two primary colours that so dominated Van Gogh’s palette in the later years – yellow and blue – find a mention here, as does the theme of rolling cornfields canopied over by an endless sky, a motif that Van Gogh kept coming back to over and over again in his career, but more particularly in the last few weeks.

Finally, Bernard spoke of the light that Van Gogh reached out to right through his tragically short life, persistently, unyieldingly – to be thwarted often, but when indeed it embraced him, in love, compassion and artistic fruition, some of the most memorable creative moments in human history were the result. Thus, when in January 1890, brother Theo wrote to announce the birth of his son, named after Vincent, Van Gogh celebrated the event in the only way he knew, by putting brush to canvas. The unforgettable Almond Blossoms – a study of white almond blossom floating against a turquoise-blue sky, nearly filling it up – came to life. “How glad I was when the news came”, he wrote to his mother,”...(and) I started right away to make a picture for him, to hang in their bedroom, big branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky”. Few works of art have been more brilliantly irradiated by hope and the joy of life than this canvas. And yet, only six months later, Van Gogh was to feel that the light was going out of his life, that the skies were closing in on him. The revolver with which he shot himself on July 27, 1890, lay on a low stool not far from Bernard’s letter inside the gallery.

Almond Blossoms by Vincent Van Gogh is among the few works of art that have been so brilliantly irradiated by hope and joy of life. Credit: Anjan Basu

Like most Van Gogh admirers, I had read his letters to Theo and others (in English translation, of course), as well as some he received from them, but it had never struck me that his correspondence could be such a valuable guide to the museum itself. So I reached this gallery at nearly the end of my tour, intending it to be my last stop in the museum. I had to soon change my plan, however, going back to some of the canvases I had already seen, after Van Gogh’s letters opened for me the door to a treasure house of associations and memories.

"In the little over two months (May-July, 1890) he lived in Auvers-sur-Oise, a picturesque little town on the Oise, not far from Paris, Van Gogh produced more than 80 paintings and 60 drawings. This furious burst of creativity was his refuge from the “desperate loneliness” that haunted him, as he tells Theo. “They (three recently-done canvases, presumably Wheatfield under Thunderclouds, Wheatfield with Crows, Wheat Stack under Clouded Sky) are vast stretches of wheat under troubled skies”, he wrote to Theo on July 10, “and I didn’t have to put myself out very much in order to try and express sadness and extreme loneliness”. He was aware of the deceptive quiescence of his illness, and told his brother that he didn’t know “how things might turn out with me”. Little Vincent’s illness, Theo’s failing health, his problems at work at the art dealers’ that employed him, coupled with Theo’s (and his wife’s) worries about money took their own toll on Van Gogh who was completely dependent on his brother’s support.

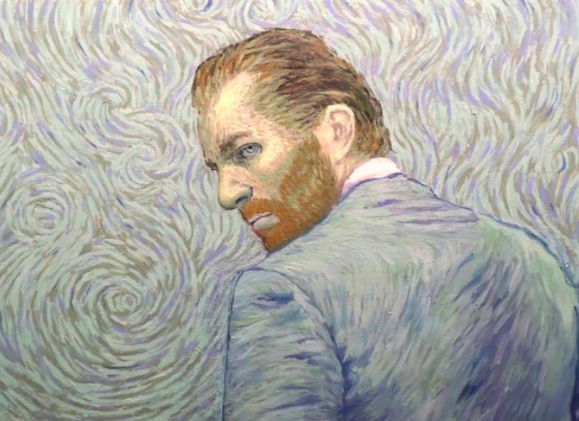

In Wheatfield with Crows, it looks as though everything is about to be crushed, wiped out, in a cataclysm which will sweep earth and sky into one torrent shot with gold. That must be why it is widely, though wrongly, believed to have been Van Gogh’s last work. But the same restlessness, the same presentiment of doom seemed to me to permeate some other paintings from these months as well, in varying degrees: The Church at Auvers Cottages at Cordeville or Street at Auvers, for example. Despite the feverish energy Van Gogh brought to his work here, his powers seemed to him to be slipping away, his palette was less rich, less brilliant now than during the Arles period (February 1888-April 1889), and the dominant colours now were milky white, subdued green, faded yellow and mauve. Often, the lines he drew were somewhat wobbly, the branches of trees writhed in convulsions like the cypresses he painted while at the asylum at Saint-Remy, the sky was stormy and even the ground looked as though it were shaken by an earthquake. "Surprisingly though, in a letter to his mother written around this time, Van Gogh speaks of “a mood of almost too much calmness”, though he also writes wistfully about his own childhood, which he sees “as through a glass, darkly—so it has remained; life, the why or wherefore of parting, passing away, the permanence of turmoil – one grasps no more of it than that”. This mood of wistfulness seems to colour Wheatfield under Thunderclouds, one of his last efforts, too. Here Van Gogh, on his own admission, is “completely absorbed in that immense plain covered with fields of wheat against the hills boundless as the sea in delicate colours of yellow and green...”

"In one of the most perceptive critiques of Van Gogh’s work to have appeared in his lifetime, Albert Aurier (whose own life was cruelly cut short by typhoid, at 27 years) wrote in the Mercure de France in January, 1890: “What we see is an all-embracing, wild, blinding glow; matter, the whole of nature in crazy convolutions, in a raging frenzy, intensified to the point of utmost agitation; it is form become a nightmare, colour become flame and lava and precious stone; it is light become conflagration; it is life burning fever”.

Aurier’s point of departure was Van Gogh’s Sunflowers series, as well as the many extraordinary portraits of the Arles period, together with canvases like The Terrace Cafe. He went on to say that “he is, so far as I know, the only painter who perceives the range of colour of things with this intensity, with this metallic, gem-like quality”. Only Van Gogh could have responded to Aurier the way he did: “...things seem to have mistakenly attached to my name that you would do better to link to Monticelli, to whom I owe so much”, he wrote to Aurier on February 11. “I also owe a great deal to Paul Gauguin, with whom I worked for several months in Arles...Your article would have been fairer, if when dealing with ... the question of colour, you had – before speaking of me – done justice to Gauguin and Monticelli. For the role attaching to me, or that will be attached to me, will remain, I assure you, of very secondary importance”. For good measure, he underlined the last sentence with a pen that had a very thick nib.

The Yellow House by Vincent Van Gogh, where he had taken up lodgings, hoping that “there I can live and breathe, think and paint”. Credit: Anjan Basu

As you hear the name of Gauguin, you inevitably look back on The Yellow House, the 2.5 ft-by-3 ft canvas in which a buttery yellow house “with raw green shutters .... stands in the full sunlight on a square which has a green garden with plane trees, oleanders and acacias....And over it the intensely blue sky”, as Van Gogh was to write to his sister Wilhelmina. This was the house in Arles where he had taken up lodgings, hoping that “there I can live and breathe, think and paint”. This was also where he had planned to set up a painters’ cooperative and, with high hope, had invited Gauguin to join him in the community. The disaster that this project ended in and the awful burden that Van Gogh carried for the rest of his years on that account come back to you with great force. As for Monticelli, you are not even sure that you had heard that name before!

It is a deeply-entrenched tradition to associate Van Gogh with the tragic, with death foretold, as it were. After all, he died when he was only 37, and he had thought of suicide even earlier, as he confided to Theo more than once. Of his contemporaries, Monet lived to be 86, Renoir 78, Degas 83, Emile Bernard 73. Only the bohemian Gauguin’s productive life could be said to have been cut short at the age of 55. And yet, to let your eyes and your mind savour the prodigious profusion of form and colour in Van Gogh’s oeuvre is to completely belie a sense of tragedy. Even his letters, perhaps more than any other artist’s, are a celebration of life.

"Writing to Theo on April 13, 1888, Van Gogh spoke about a triptych he was planning around orchards that were bursting into life around him in his first few weeks in Arles. He included in his letter ink sketches of the planned paintings also, and once I had looked at that letter, I had to go back to the gallery where some of the completed canvases were displayed. The Pink Orchard, The Pink Peach Tree, The White Orchard are some of the most luminous works with paint and brush ever done by any man. Here, if anywhere, was beauty and light that defied death. “The painter of the future is a colourist such as has not existed before”, he wrote to Theo at around the same time that he worked on his orchards. Vincent Van Gogh little knew that he himself was that colourist of the future.

Anjan Basu freelances as a literary critic, translator and commentator. ‘As Day is Breaking’ is his book of translations from the work of the noted Bengali poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay.

This article went live on March thirtieth, two thousand eighteen, at thirty minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.