A Decisive Decade for India: Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s Last Essay

The following is excerpted from the book India's Tryst With the World: A Foreign Policy Manifesto, edited by Salman Khurshid and Salil Shetty, published by Vintage, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

India was confronting a severe economic and financial crisis in 1990 and there was a pervasive sense of pessimism about India’s prospects. The external environment was in a state of unprecedented flux as the Cold War neared its end. India had to adjust to a vastly transformed international landscape. And yet, within just a few years, India emerged as one of the most promising emerging economies, a vibrant plural democracy and a key international actor. It had harnessed an idea whose time had come, that of the economic transformation of the nation.

Today, we are confronted by multiple crises no less challenging than those in the early 1990s and need to embark on a more ambitious journey towards our tryst with destiny. We are at a rare inflection point when the flow of history changes course in unexpected directions. The world is reeling from the impact of twin crises—a public health crisis brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic and an economic crisis triggered by the multiple disruptions in economic activities across the world. In many developing countries, the choice before decision-makers is stark: to save lives by suspending economic activity or suffer the wiping out of livelihoods, especially of those located at the very margins of survival. India, too, has had to contend with these choices. In its initial phase, there were assessments that once the pandemic receded, there would be a return to equilibrium, altered as that may be in some respects.

We must be clear that the world we left behind in March 2020 is gone forever. Our energies must be harnessed to adjust to a new and still-changing situation around us. This will compel the search for new ways of living, working and exploring new opportunities even as familiar anchors in our lives disappear in this unfamiliar and rapid spate of change.

This was not the first time that India had to deal with an existential crisis. In 1990, the Indian economy was on the brink of bankruptcy and on a downward economic spiral. As the Cold War came to a close, equations among major powers changed dramatically, forcing countries like India to navigate an unfamiliar global geopolitical landscape. There was widespread pessimism about India’s prospects as a front-ranking nation.

And yet, this moment of darkness was also the moment when seminal decisions were taken both in economic policy and in foreign policy, which, in just a few years’ time, transformed India into one of the fastest growing emerging economies of the world and an influential actor on the international stage. What are the lessons to be drawn from that recent history?

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty.

One, India flourished as it became a more outward-oriented economy, embracing the steady and measured globalization of its economy. The winds of competition that began to flow through the Indian economy helped create globally competitive Indian enterprises. The fears about Indian industry being hollowed out or the Indian market being inundated by foreign goods were quickly and comprehensively belied. As the Indian economy continued to grow at unprecedented high rates, spurred by a series of reform and liberalization measures, living standards improved and employment expanded. Through its participation in a number of regional and bilateral free trade agreements, India became more and more integrated into the global economy. Its share of global trade steadily improved from about 1 per cent to about 3 per cent at its peak. India also became a more attractive destination for foreign capital flows both in the portfolio and fixed assets category. And this also brought advanced technologies and modern management into our corporate sector.

In judging the value of free trade or economic partnership, these other significant benefits are sometimes lost sight of. One should not look at these agreements only from the standpoint of exports and imports. It is in this context that there are valid concerns about recent trends in India’s external economic policies. The long-term trend towards the progressive lowering of tariffs has been reversed over the past several years, and there is a growing negative sentiment on bilateral and regional free trade arrangements. India’s decision to stay out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was, in my view, against the spirit of the economic reforms and liberalization, which successive governments not only sustained but deepened further, irrespective of their political persuasion. By not participating in the RCEP, India may have pushed itself to the margins of the most dynamic component of the global economy, which is now centred in Asia.

Two, during the initial phase of economic reforms and liberalization, India did not pay as much attention as it should have to promoting economic integration within its own proximate region of South Asia. It soon became clear that the ‘Look East’ policy of strengthening our economic and trade links with Southeast Asia and East Asia could not bypass our neighbours even if Pakistan was reluctant to be part of region-wide economic cooperation. A politically unstable and economically deprived periphery will always keep India preoccupied and constrain its regional and global role. This is the reason that, at the turn of the millennium, India adopted a ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and became one of the champions of regional economic integration, embracing the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) as a platform for such cooperation.

It was in this context that I had declared that while I did not, as the prime minister of India, have the mandate to alter India’s borders, I did have the mandate to make borders in South Asia progressively irrelevant, so that there could be a free flow of goods and peoples across the region and a celebration of our shared cultural affinities. India’s relations with Pakistan have always been complex and adversarial, but I do believe that India must remain committed to the goal of an economically integrated South Asia, including Pakistan. The promotion of trade and economic cooperation between India and Pakistan has huge potential, as study after study has confirmed. This must remain on our agenda even if it looks unachievable at this time. Regional economic integration must be anchored in physical connectivity through highways, railroads, waterways, air links and, in our increasingly digital world, digital connectivity.

It is encouraging that we have seen considerable progress in this regard with India investing in greater connectivity with its neighbours. Several integrated checkpoints (ICP) have been established on our borders with Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, providing immigration, customs and testing facilities at a single location. Such improved border infrastructure must be accompanied by more efficient bureaucratic procedures. Over the past few years, a sub-regional power grid and market has emerged under the BBIN (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal) framework, and river transport between India and Bangladesh is now taking place, reviving what used to be the main transportation network in the eastern part of the subcontinent. Much more remains to be done with the aim of making India a veritable engine of growth for the entire South Asian region. Progress in this regard, I am convinced, will have a positive impact on relations among the states of South Asia.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

I am also deeply concerned about the impact of climate change and ecological degradation in our region. There is evidence that the Himalayan glaciers are melting at a rapid rate, which will affect the flow of the snow-fed perennial rivers of the Indo–Gangetic plains. There may be a rise in sea levels, which will not only affect people living on islands but also the coastal plains across our region. Weather patterns are changing, with the monsoons becoming more and more unpredictable.

The heavy use of toxic pesticides and chemical fertilizers are contaminating our rivers, and these effluents flowing into the seas around us are creating ‘dead zones’ in the Bay of Bengal and other maritime zones. The rich biodiversity for which our region is well known is being depleted at a faster pace than before as forests are encroached upon and the habitat of our wild species shrink even further. The Covid-19 pandemic was a reminder of what may happen as wild species are driven from their natural habitat into closer contact with human populations, creating opportunities for rare viruses to jump from animals to humans. These are ecological challenges that countries of South Asia must face together and collaborate in mitigating their impact. As the largest country in the region, it is only India that can take the lead in this respect.

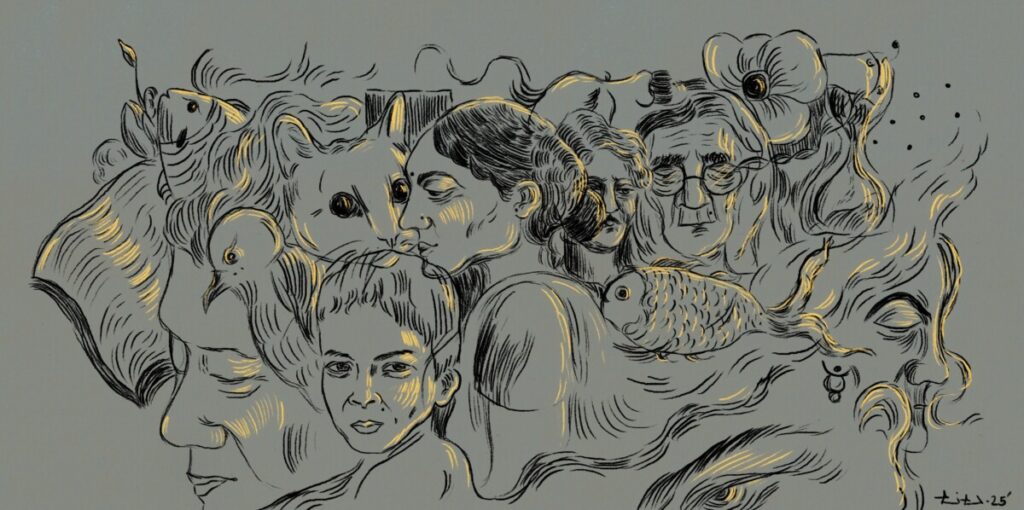

India is at the heart of Asia, located at the crossroads of ancient maritime and caravan routes. As a result, it also became a melting pot of peoples from across the vast expanse of Asia, creating over the centuries an extraordinarily diverse country with a deeply cosmopolitan and accommodating temperament.

Every religious faith known to the world is represented here. There is no stream of creative ideas that has not, at some point in time, been explored by the sages and great thinkers of this land. The poets and writers of the subcontinent’s numerous languages have delved deep into the spiritual yearnings of humanity. It is this intricate civilizational fabric woven with strands of every colour and shade that gives Indian culture its universal appeal.

One of the great strengths of India, as it adapts to a rapidly changing world, is its ability to manage immense diversity. The embrace of plural democracy by independent India enshrined in its Constitution was in many ways a natural continuum. In an increasingly globalized and congested world, India’s cosmopolitan spirit is an asset few countries enjoy. We must continue to leverage this spirit to our advantage rather than seek to impose a monochromatic frame over it.

Globalization is the outcome of the forces of technological change that has knit the world together in a dense web, crisscrossing national and regional frontiers. This is unlikely to be reversed even if it is temporarily stalled. This networking effect has generated unprecedented wealth, but the distribution of benefits has been uneven both among states and within states. The backlash against globalization, the surge in narrow nationalist and even parochial sentiments is rooted in this pervasive and rising inequality across the world. But inequality is not the inevitable result of globalization or of rapid technological advance. Inequality must be blamed on the failure of public policy. States have not delivered on their responsibility to ensure equitable distribution.

India is hardly an exception in this regard. What this points to is the continuance of the trend towards greater globalization and, therefore, winners of the future will be those countries that stay ahead of the globalization curve. This must be accompanied by policies that ensure even distribution of the rising wealth and incomes that are generated by globalization thorough progressive taxation, the continual skilling and training of manpower to cater to a whole new spectrum of demand and giving full play to education from the primary to the tertiary and advanced levels.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

During the pandemic, there was a perception that globalization is stalling, even reversing in some manner. That is certainly not the case with the digital economy, which has now become a significant component of all economic activity. The pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital technologies and this is reinforcing globalization. India has unique strengths in this regard because of its well-developed IT sector, the early adoption of the Aadhaar unique identification system, and the rapid progress in Internet penetration and spread of mobile telephony. All the ingredients for a quantum leap into the digital future are now present. What we need are policies that enable us to fully leverage them.

One of the defining trends of our contemporary world is the rising salience of challenges that are cross-national and global in character. They are not amenable to national solutions even for a rich and powerful country. The pandemic that swept across the world was one such challenge. Climate change is another.

But these are only the most serious and urgent. There are several others, such as the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the growing menace of drug trafficking and international terrorism. There are newer domains, such as cyber security and the security of space-based assets, on which much of our economic activity is dependent.

These challenges demand collaborative approaches on a global scale. And yet, precisely at a time when the need for such global collaboration is both pressing and urgent, we are witnessing a retreat into narrow nationalism and parochial responses. We saw this in the phenomenon of ‘vaccine nationalism’, despite it being obvious that ‘no one is safe unless everyone is safe’. This is the great paradox of our times. We do have the United Nations (UN) and several specialized agencies such as the World Health Organization, but they lack empowerment and resources. Instead of serving as platforms for multilateral processes and international cooperation, they have instead become the arena for national contestations. This ensures that even if some agreement is reached, it is usually a lowest common denominator option.

It is legitimate for countries to attach greater priority to interests of their own people. But no definition of national interests can be in absolute terms when we are functioning in a multi-state landscape. A spirit of internationalism, a sense of serving a larger humanity are important if there is to be a real chance for peace and fraternity. Right since Independence, India has been a champion of the United Nations. It mobilized international opinion for completing the goal of decolonization. India’s was an early voice seeking the end of the inhuman practice of apartheid in South Africa. And in the conclusion of important agreements on disarmament and international security, such as the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the Biological Weapons Convention and the Outer Space Treaty, India played a leadership role. I sincerely believe that India’s best interests would be served by assuming leadership in promoting global collaboration on critical issues of the day through the reinvigoration of multilateral approaches.

This not only requires working together with the major powers but in mobilizing the large community of developing and emerging nations that have a major stake in addressing such issues and, more importantly, in ensuring that in doing so, the principle of equity is upheld. We have established strong partnerships with several major powers, and this has enabled India to enhance both its economic and security interests. It is equally important that in this rapidly transforming geopolitical terrain, we strengthen our relations with the developing countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America, with whom we have a shared interest in promoting a multilateral, rule-based order and in upholding the principle of equitable burden sharing.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty.

During the coming decade and perhaps beyond, China will remain an enduring challenge. What lies at the heart of this challenge is the growing gap in the economic, military and technological capabilities of the two Asian giants. I have witnessed how this has had a major influence on the state of relations between the two countries. During UPA-1, China was ahead of India in terms of the size of GDP, and there was a significant gap in the two countries’ respective economic and military capabilities. However, while India was growing at the rate of 8–9 per cent per annum in those years, China’s GDP growth had started to slow down. India began to narrow the gap with China, and the world began to see India as the next big commercial opportunity after China. India was also more attractive as a partner because of its status as a vibrant and plural democracy.

This is an intangible asset but is significant nevertheless. Shared democratic values do not always ensure an alignment of interests, but when interests are aligned, shared values reinforce the convergence of interests. This is what explains the success India had in forging strong and enduring partnerships with sister democracies of the US, Europe and Japan. India’s diplomatic options expanded and the successful conclusion of the India–US civil nuclear agreement in 2008 must be seen in that context. China recognized India as an important emerging country; this was the period when the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) group came into existence and the Brazil, South Africa, India and China (BASIC) group worked together to uphold the interests of developing countries in multilateral negotiations on climate change. During my meeting with Chinese leaders, a consensus was reached on the following points:

• That China is not a threat to India, and India is not a threat to China.

• That there is enough space in Asia and the world for both India and China to grow.

• That India is an opportunity for China, and China is likewise an opportunity for India as these are the two largest and expanding economies in the world.

• That India–China relations have now acquired a strategic dimension because India and China working together can adjust the existing global regimes and shape the emerging ones in newer domains such as climate change. There should therefore be an early political settlement of the border issue in that larger strategic context.

This consensus is no longer valid, and the recent and unprecedented clashes in eastern Ladakh that started in 2020 between the forces of the two countries demonstrated this starkly. China believes it is no longer an emerging economy such as its partners in BRICS and BASIC but a power in the same league as the United States. This change has come about over a period of time, but one could sense the change in summit meetings that took place after the global financial and economic crisis of 2007–08. The asymmetry of power between China and the US began to shrink. The gap between India and China in both economic and military terms began to expand, and China keeps repeating that its GDP is five times that of India. The lesson I draw from this experience is that it is essential for India to get back on a high-growth trajectory and begin to narrow the gap in power with China. I believe that this is eminently possible, given the several positive factors that continue to favour India. This includes the demographic dividend of a relatively young population, the potential for rapid growth in digital technologies and the drawing power of India’s vast and expanding market despite recent setbacks.

Partnerships with countries that share our concerns about the unilateral assertion of power by China at the cost of other countries will be important, and the Quad is a good example of this. We should be conscious of the fact that as these partnerships gain in importance, India may have to accept greater constraint on the exercise of its strategic autonomy. I would therefore hope that our focus remains on building up our own capabilities for which accelerated growth is indispensable. India and China must find a new and sustainable basis for managing their relations, and this is not going to be an easy task.

China displays the arrogance of power and expects deference, which India will reject. A positive trend in India-China relations is unlikely in the foreseeable future, and our policies will need to be based on that premise. Enhanced preoccupation with defence both in respect of China and Pakistan will inevitably deflect resources from economic and social development. There will be greater need to deploy our limited resources more efficiently and with frugality.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

China is a material challenge. It has also become an ideological challenge. China is no longer insisting on its right to pursue its own model of social and economic development. Its undoubted economic success and, lately, its swift control over the Covid-19 pandemic has encouraged its leadership to promote the China model of what some scholars have called ‘authoritarian state capitalism’. China has been denigrating liberal democracy as a failed political dispensation and socio-economic model, pointing to the setbacks that the US and Western European countries have suffered in recent years. There is a certain appeal that the Chinese developmental model has for developing countries. Even in India we find advocates of the Chinese model.

I believe this is a misplaced and even dangerous line of thinking. India is not China and we have demonstrated in the very recent past that democracy is fully compatible with the achievement of accelerated economic growth. Many of the ills that India suffers from require more, not less, democracy, and India performs best when its most creative minds engage freely in the exchange of ideas. The success of India as a vibrant plural democracy may well determine the future of democracy itself as a political ideal. The destination and the path leading to it are spelt out with sharp clarity in the Constitution of India. Reaffirming our faith in its wisdom was never more necessary than it is today.

Dr. Manmohan Singh was an Indian economist who served as the prime minister of India from 2004 to 2014. He passed away last year.

This article went live on October eighth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.