Budget 2025: The What, Why and How of Boosting Consumption for Stimulating Growth

The Budget deals with allocating money towards areas where the government thinks it is essential to spend, and finding out ways such as taxes, to finance it. The government primarily requires money to spend on social infrastructure (such as schools, hospitals, water, sanitation, etc.), physical infrastructure (such as railways, roads, airports, etc.) and transferring funds to the poor and the deprived, so that distribution of income becomes more equal. But, how does one say whether a budget is good or bad? The general assumptions underlying a good budget are: it contains the fiscal deficit, carries on with the necessary reforms, and give incentives to consumers and business.

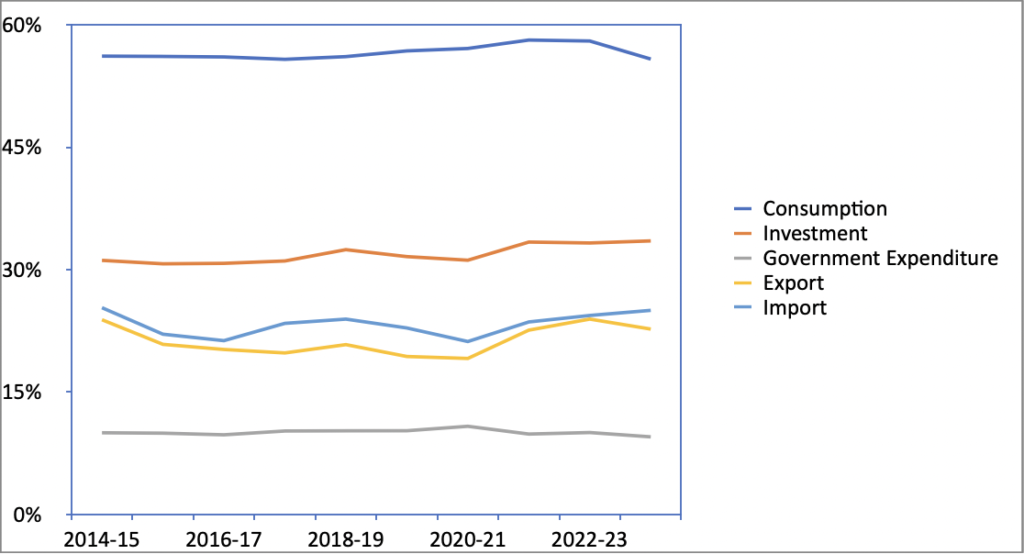

For the benefit of the reader, there are five components of demand, namely, consumption expenditure, investment expenditure, government expenditure, exports, and imports. The most important component of demand is consumption expenditure, explaining around 57% of the national income. Generating and sustaining income would therefore call for strategies that would generate income and thereby sustain consumption.

Source: Indian Economic Survey, 2024.

Until the middle of 2024, the Indian economic outlook looks quite optimistic, with predictions of continued growth at a rate of over 7%. However, when India posted a lower growth rate of GDP – 5.4% in the second quarter of 2024, the economic outlook quickly turned pessimistic. According to the government's own estimate, GDP growth is expected to hit a four-year low at 6.4%. Other metrics of economic growth are also disappointing, with declining urban and rural consumption, single-digit growth in GST collections (7.3% year-over-year in December 2024), and core infrastructure growth (4.3% year-over-year increase during November 2024).

There has been a fall in car, two-wheeler, and cement production. In fact, the PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index), which tracks sales, employment, inventories, and price data of manufacturing sector companies, has shown a sharp decline to 56.4 – the lowest in 12 months.

Therefore, the Union finance minister is expected to introduce policy measures aimed at boosting consumption, such as increasing tax exemptions. Additionally, efforts should be made to create a more favourable business environment by reducing the cost of doing business, for instance, through increased fund allocation for physical infrastructure and implementing necessary reforms to eliminate the long-standing inverted duty structure (IDS).

This will help to alleviate the consumption distress among the middle class (with an annual income between Rs 5 lakhs and 30 lakhs) and lower income households (with an annual income between Rs 2 lakhs and 5 lakhs) which form the backbone of India’s growth story. The majority of these groups are employed in the agricultural sector, self-owned businesses, and the MSME sector. Together, they make up 70% of India’s working population with 400 million stuck in low productive agriculture sector and around 250 million in the MSME sector.

The agriculture sector has struggled to flourish, with 82% of farmers classified as smallholders, owning less than 1.15 hectares of land. Moreover, these land parcels are often not contiguous, making the mechanisation of agriculture difficult and contributing to low agricultural income. India’s labor productivity – economic output per hour of work – is just 12% of the US levels. In purchasing parity terms, GDP per hour worked is $81,800 for the US, in comparison to India’s $10,400. This also explains lower per-capita income in India, which can only grow with more incentive for agriculture and MSME sectors.

The MSME sector which for long has suffered from the inverted duty structure (IDS). A recent study by CUTS International of 1,464 tariff lines across textiles, electronics, chemicals, and metals reveals how the IDS is hurting competitiveness, with 136 items from textiles, 179 from electronics, 64 from chemicals, and 191 from metals most affected. IDS implied the MSMEs are not competitive as their input cost is higher and therefore has difficulties in scaling up.

Also read: Balancing Reform and Reality: The GST Dilemma for MSMEs

MSMEs produce goods typically consumed by low and middle-income households, which have a higher marginal propensity to consume. These businesses are integral to daily life, offering products and services ranging from baby food and biscuits to medicines, education, healthcare, hotels, and travel.

Over the last few years, tax reforms have only benefitted the big corporate sectors. India's success story in manufacturing has traditionally been driven by a capital-intensive mode of production, with major corporates like Reliance, TATA, Birla, and others dominating the sector. However, these corporate houses are not able to create enough employment opportunities which is needed for sustaining consumption.

Between 2016 and 2023, people in the bottom 20 quintiles has seen their income growth decline by 20% whereas those in the top 20 quintiles has seen their income grow by 20%. The growth in income for this top 20 quintiles is because of highly skilled new-age workforce (often foreign returned) like doctors, legal experts, engineers and MBAs working for the global consultancy firms and global capability centres of multinational based in India. On the other hand, a growing economy is also witnessing creation of low-paid and low-productive jobs such as housekeeping, security services, and other gig type jobs such as Zomato delivery boys, which in a way is contributing to widening income inequality.

Due to lack of adequate skills and inability to absorb labourers in capital intensive manufacturing, migration is happening from agriculture to low-skilled services sectors. Even for the middle-class population they are facing problem with higher cost of healthcare and education. At a time when public spending (Central and State governments taken together) is only 4.5% of GDP, it is not surprising that for a majority of the population, education is delivered by the private sector.

A higher allocation of funds towards education and healthcare is essential, alongside a focussed intervention in agriculture and MSME sectors. As long-term data suggests, countries like China, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand were able to grow their per-capita income by investing in quality primary education and healthcare systems – an approach that can be replicated through sustained, increased budgetary allocation.

Nilanjan Banik is professor, Mahindra University, Hyderabad.

This article went live on January thirty-first, two thousand twenty five, at forty-one minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.