Decoding the Great Demonetisation Puzzle

Analysis using Milton Friedman's theory shows India's GDP growth is likely to crawl back to its long-run level. However, we cannot deny the loss in interim GDP because of demonetisation.

People wait in queues in a bank to exchange their 500 and 1000 currency notes in Allahabad. Credit: PTI

This week marks the one-year anniversary of the great Indian demonetisation move. India's move should not be looked at in isolation. One can find instances of demonetisation elsewhere too. In October 2014, Singapore got rid of 1000 dollar notes, in 2011, Canada stopped issuing 1000 dollar notes, and in 2013 Sweden did the same with 1000 krona notes – all as a way to stop financial crime. Economists Larry Summers and Kenneth Rogoff also suggested doing away with high denomination 100 dollar notes to prevent money laundering and tax evasion.

However, in India, economists were widely divided over the efficiency and the impact of the move on black money, which is variously estimated at 23% to 75% of India's GDP. Unlike most developed economies, which mostly rely on cashless transaction, for India, a majority of the population was dependent on cash for day-to-day transactions, and hence the hardship from the demonetisation move was much more.

Why demonetisation in India?

Demonetisation was intended to flush out black money, encourage a move to a cashless state and bring the parallel sector into the mainstream economy. Data from the Ministry of Finance, government of India reveals that during 2014-2015, only a meager 4% of Indians paid tax, with the government losing between Rs 6 to 9 lakh crore on account of people evading tax. The demonetisation move was also seen as a way to tackle counterfeit currency. A study undertaken by the Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, estimates counterfeit value at Rs 4 billion, with the old Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes accounting for three quarters of counterfeit notes.

Finally, the move was seen as a nudge strategy for greater financial inclusion. Financial exclusion imposes a high cost on people. In India, 98% of people use non-banking channels such as hawala, and pay exorbitant costs to remit or receive money from their family members living in other regions. A survey of Indian migrant workers shows an average commission of 4.6% when transferring money through informal routes, whereas transfer through formal banking system comes at no cost. Importantly, the demonetisation move has operationalised Jan Dhan accounts which were seldom operational.

The critiques

However, critics point out demonetisation is unlikely to bring out much black money, since the bulk of it is held in illiquid assets such as land or gold and jewellery. Without taking supplementary policy measures to track the stock of undeclared wealth, the fight against black economy deserves little merit. In fact, 98.96% of the scrapped Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 notes returned to the Reserve Bank of India by the end-June, 2017. Also, only 3.4% of all the notes that came back to the system post-demonetisation were fake. And most of the financial inclusion that has happened thanks to demonetisation was because poor people started depositing unaccounted money of the rich and corrupt, into their own bank accounts for a commission (with a promise to pay back at a later date). Meanwhile, the common man has had to bear the economic hardship as 90% of all transactions are paid for in cash. The brunt of the impact fell on those associated with the informal sector, which accounts for 80% of all jobs, where 85% of the workers are paid in cash.

Also read: The Vast Difference Between What Demonetisation Achieved and How it was Perceived

Examining demonetisation

Although each one of the above arguments deserve merit, we need to understand the path through which the demonetisation move has affected the economy. A way to examine the effect of demonetisation is to use the famous Milton Friedman's Quantity Theory of Money equation. The 1976 Nobel laureate argued that inflation is a monetary phenomenon and he depicted the money market (that is, demand and supply of money) through the following equation:

MV=PY (1)

where, M is the money stock in the economy, V is the velocity of money (the number of times currency changes hands, so that MV becomes the amount of nominal GDP that the money supply can generate), P is price level, and Y is the real value of output.

Going by equation (1), when demonetisation was announced, the first thing that happened is a reduction in money supply. Indeed, as Table 1 shows, there has been a fall in currency in circulation, and commercial banks lending to businesses. Concomitantly, there was an increase in bank deposits. People were busy depositing money, mostly in their Jan Dhan accounts.

Statement on Money Supply

| Year-on-year | ||||

| Components of M3 | March 4, 2016 | March 3, 2017 | ||

| Amount (Rs, Billion) | % | Amount (Rs, Billion) | % | |

| Currency with the Public | 1839.7 | 13.3 | -4384.8 | -27.9 |

| Demand deposits with Banks | 758.3 | 8.6 | 2373.6 | 24.8 |

| Time deposits with Banks | 8474.1 | 10.3 | 10136.9 | 11.2 |

| Bank Credit to Commercial Sector | 7719.8 | 11 | 3012.2 | 3.9 |

Source: Database on Indian Economy.

Two other things have also happened. Compared to other emerging economies such as Brazil, China, Russia and South Africa, in India we have a higher currency-to-GDP ratio. With a reduction in currency in circulation, there is therefore a likelihood of V also falling. What then follows from the quantity theory of money equation is that with a fall in M, there will also be a fall in P and Y.

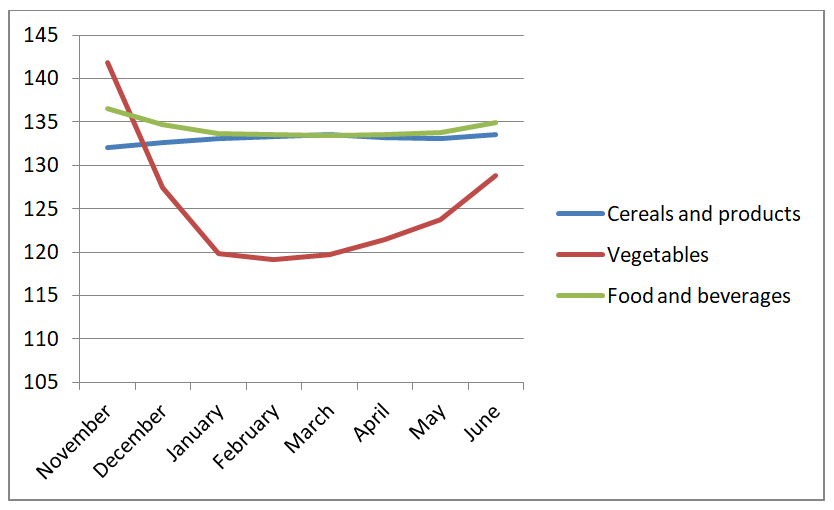

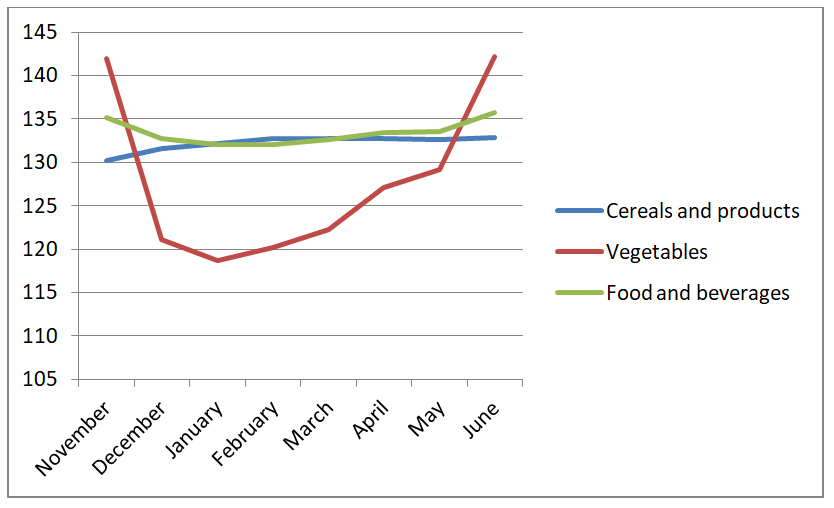

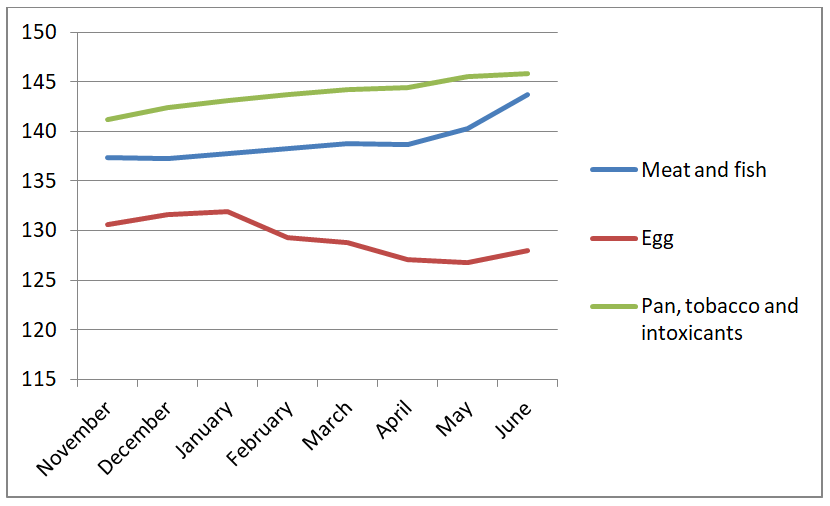

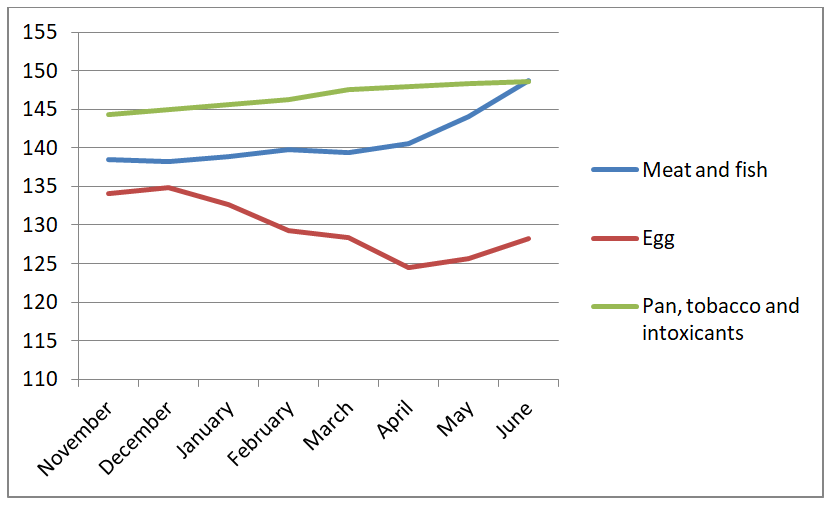

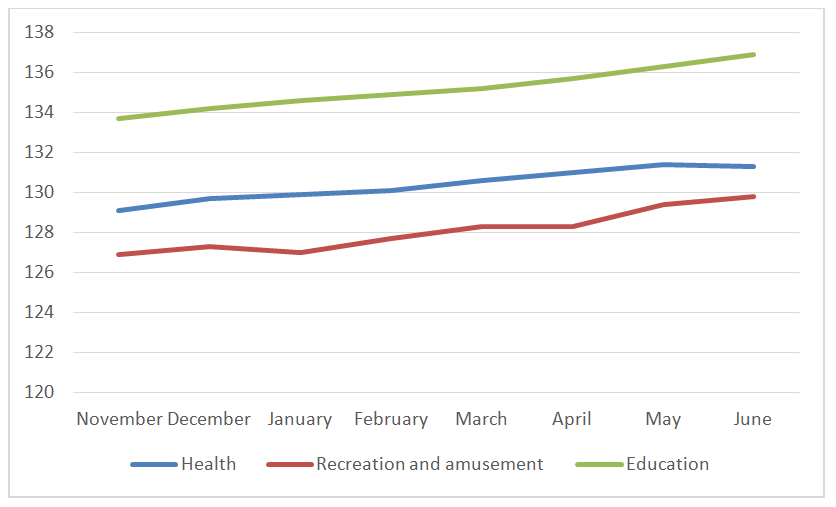

In fact, that is something that is clear from the following figures. It is interesting to note that the price of vegetables, eggs, foods and beverages, all fell during the period following demonetisation. The price of less income inelastic items such as education, healthcare, pan, tobacco and intoxicants, did not fall.

This is quite natural: whether people have income or less income, if they fall sick they will have to visit the doctor. Similarly, for sin-items such as pan, tobacco, and intoxicants, the addicted do not care whether they have income or less income. What is however surprising is that the price of meat items shows an increase post-demonetisation. The causal relation of the Uttar Pradesh meat-ban (leading to less supply of meat in the market and hence a higher price) is yet to be scientifically validated, but that can be a possibility. In these graphs, to capture the effect of demonetisation on prices we consider the Consumer Price Index. The data is sourced from data.govin.

Impact on prices in rural India (cereals, vegetables)

Impact on prices in urban India (cereals, vegetables)

Impact on prices in rural India (meat)

Impact on prices in urban India (meat)

Price impact on healthcare, recreation and amusement, and education

With prices falling, as predicted by equation (1), income will also fall. In fact, during the following quarters, India's GDP growth rate fell from 7.3% to 7% (February 28, 2017); 6.1% (May 31, 2017); and 5.7% (August 31, 2017).

Economists, not favouring the demonetisation move are using these numbers, and saying India could have realised 8% plus growth rate, had the government not undertaked demonetisation. According to the International Monetary Fund, the size of the Indian economy is $2.54 trillion (nominal, 2017) and $ 9.48 trillion (Purchasing Power Parity, 2017). Hence, this 2.5% to 3% difference (what GDP could have grown without demonetisation and what it has grown with demonetisation) is indeed a big number.

In fact, the reduction in GDP growth rate takes away from the government's claimed success in tracking down black money and shell companies. Finance minister Arun Jaitley in a press interview announced that between November 2016 and the end of May 2017, the income tax authorities detected a total of Rs 17,526 crore in undisclosed income and seized Rs 1,003 crore. As a result of the demonetisation drive, there had been a substantial increase in the number of Income Tax Returns filed. The number of returns filed as on August 5 registered an increase of 24.7% compared to a growth rate of 9.9% in the previous year. The government has identified more than 37,000 shell companies that were engaged in hiding black money and hawala transactions. The income tax department has identified more than 400 benami transactions up to May 23, 2017 and the market value of properties under attachment is more than Rs 600 crore.

Also read: One Year Later, There Can Be No Monetary Value Attached to the Destructive Costs of Demonetisation

Friedman: The saviour

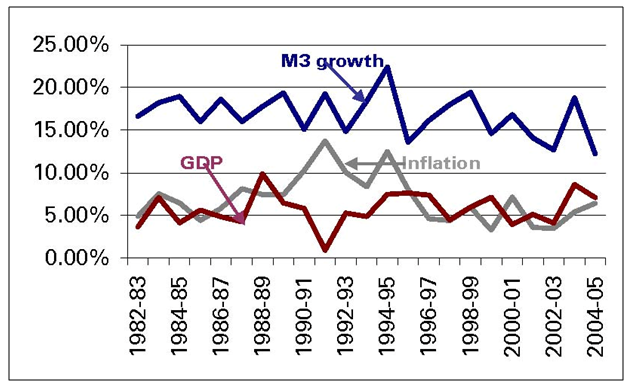

Economists supporting the demonetisation move can always argue that Friedman also said that inflation, or for that matter deflation because of demonetisation is a temporary phenomenon, and is not likely to affect real output in the long run. Students of economics know this phenomenon as a long-run vertical Phillips curve. While it is difficult to arrive at any concrete conclusion, plotting historical data, it does appear that peaks in money supply growth correspond with peaks in inflation.

Validity of the Friedman relation

Ex-RBI governor and the former chairman of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory council, C. Rangarajan also argues for a strong link between money supply growth and inflation. He finds the long-run elasticity of money supply with regard to money supply is close to unity. This is the likely basis for the RBI’s consistent belief in the role of money supply in affecting inflation.

So, it seems that Friedman's concept is valid for India, and India's GDP growth will crawl back to its long-run structural level. Having said that, one cannot still deny the loss in interim GDP that India experienced because of demonetisation. In all fairness, one has to give credit to the government when it says that more people are now filing tax returns, (though some have disputed this).Whether this nudging strategy will eventually help the government collect more taxes in the future in comparison to GDP lost at present, only time will tell.

Nilanjan Banik is a professor at Bennett University. He is author of the book The Indian Economy: A Macroeconomic Perspective.

This article went live on November eighth, two thousand seventeen, at fifteen minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.