Dollar's Hegemonic Might is Waning Amidst Rising Volatility in Geo-Economic Churns

Long before “dollar dependency” became a concern in policy circles, the global financial system had already been shaped around it. In 19th century, trade was built on the classical gold standard while the British pound was traded backed by Britain’s colonial might and economic power.

Since the Great Depression, as the world order gave greater significance to the US-led economic management system, that role of a monetary-policy anchor shifted from Britain’s gold standard system to the Bretton woods arrangement created to financialise and popularise the U.S. dollar. US’ post 1945 global foreign policy project was built on a gradual dollarisation of the world-to be adopted by both, the developed and developing system.

But the US dollar didn’t just become an important medium of exchange, it became the backbone of a new financial order, supported by international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank, reinforced by US Treasury markets and its government backed securities.

Oil, from West Asia to Latin America, which is the world’s most strategic and necessitating commodity-based trading good, has long been priced in dollar, created by the US anchored petro-dollar market, which has sought to link all energy trade directly to American influence.

Amidst the changing geo-political and geo-economic system under Trump, that system may still hold, but the American grip on this is loosening and waning in significance.

Countries around the world are building workarounds, through gold, bilateral trade in other currencies and digital payment alternatives. For India, this shift is about reducing exposure to global turbulences. The lesson is clear, a global finance is not just about efficiency, it’s about power and when that power becomes too concentrated, countries look for ways to rebalance the system.

From the Indian perspective, it entered that system through the back-door context of crisis-managed desperation.

In 1991, as our foreign exchange reserves were getting depleted fast we were forced to pledge gold to survive. What followed was the textbook definition of economic liberalisation but also with that – financial submission. The Reserve Bank’s independence may have grown, but so too did its dependence on managing capital flows, defending the rupee and building dollar reserves not as an asset of strength but as insurance against exposure.

Over the past three decades, India has amassed a formidable war-chest in forex accumulation, more than $700 billion in foreign exchange reserves. But that reserve pile is less a reflection of autonomy and more a built-up hedge against volatility.

When oil prices rise, when the Fed hikes rates, when U.S. sanctions ripple through global markets, India doesn’t escape the shock. It absorbs it. The rupee slides, capital exits and the RBI steps in to stabilise. It’s a dance we willingly do which is even very well-choreographed elsewhere.

Yet beneath this decades-long dependence, the contours of change have emerged. Central banks from China to Poland are adding gold at record rates. BRICS members are trying to settle trade in local currencies. Even close US partners are debating whether their gold should remain in New York vaults. Something is shifting through gradual and structural recalibration which might have not predicted.

India now finds itself between two worlds: one it knows too well and one it does not fully trust. The question is not whether the dollar will collapse, it won’t (anytime soon at least) but whether it will remain unchallenged. And in a world searching for alternatives, India must decide what role it wants to play and whether any other currency has yet earned the right to lead.

India’s place in the new reserve shuffle

As global trust in the neutrality of financial systems wears thin, central banks have started redrawing their reserve maps by building around it. Between 2022 and 2024, these very central banks and their respective governments purchased over 3,100 tonnes of gold, nearly double the average annual pace of the previous decade.

For India, this translated into 19 tonnes added in just the first quarter of 2024, bringing the RBI’s total to over 817 tonnes. The number is modest by global standards, China added 225 metric tonnes over the same 16-month period, but symbolically, it aligns India with a global strategy of hedging rather than defecting.

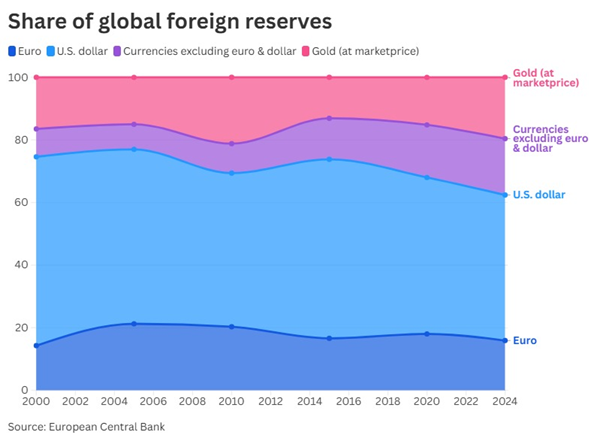

By mid-2025, global official gold reserves approached 36,000 tonnes. Gold now accounts for nearly 20% of global foreign exchange holdings, quietly overtaking the euro’s share of 16%. The dollar still dominates at around 46%, but its grip is loosening. From 71% in 1999 to under 60% today, the dollar’s decline is gradual yet persistent and it’s not just markets responding, it’s states.

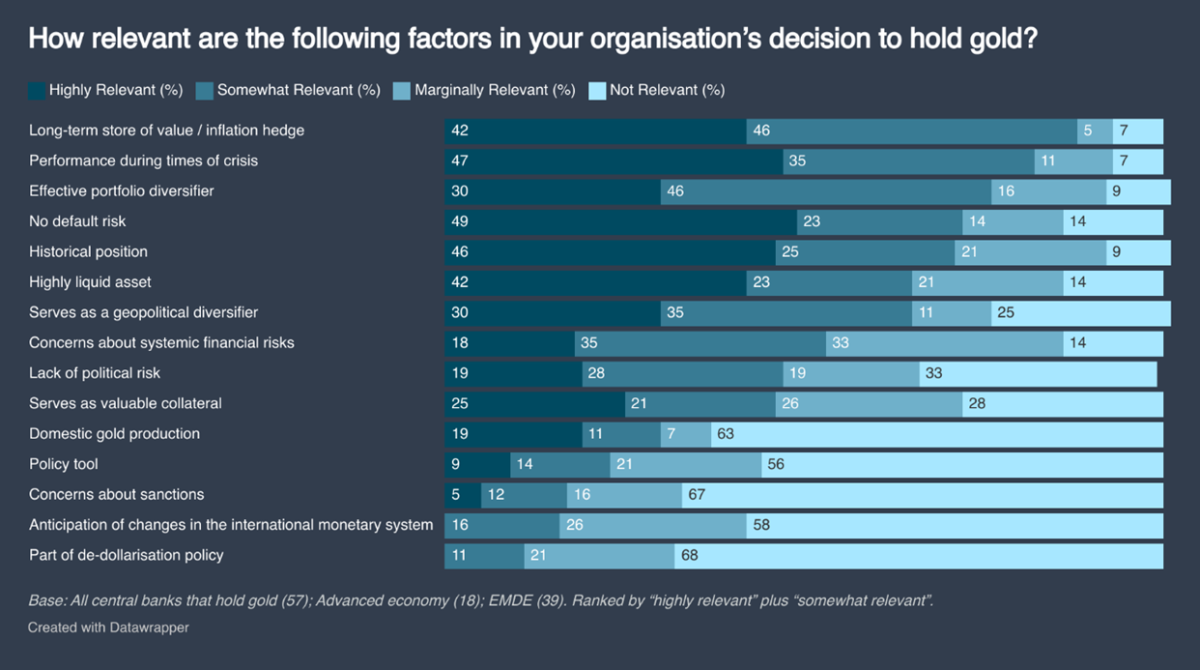

A 2025 World Gold Council report shows 82% of central banks value gold for its crisis resilience, 88% for long-term stability and 72% for its insulation from “no default risk”, an implicit response to Western sanctions, especially the freezing of Russia’s $300 billion in dollar reserves.

India isn’t leading this shift, but it’s watching closely and moving deliberately. Initiatives like the rupee–dirham settlements with the UAE, modest but consistent gold purchases and participation in BRICS discussions on alternative payment mechanisms all point to a layered strategy. This is more than a pivot away from the dollar, it’s a diversification of exposure in anticipation of systemic uncertainty.

But for all the shifting sentiment, no single challenger has earned the right to replace the dollar. The euro has continued to remain an institutionally fragmented and politically risk-averse. The Chinese yuan, despite bilateral trade traction, still operates within a framework of capital controls, state opacity and limited convertibility. Even India’s own rupee, despite ambitions of internationalization, lacks the depth, liquidity and credibility needed for global uptake.

What’s taking shape isn’t a changing of the guard, but a rearranging of the room. As Barry Eichengreen notes, the end of dollar dominance, if it comes, will be gradual, fragmented, and nonlinear. The world isn’t switching away from the dollar. It’s slowly routing around it and in that emerging design, India is wiring itself with caution and quiet intent.

The question now isn’t whether this transition is real but what should India must do to navigate the complexities of this new terrain. Because in a world where no one currency can command trust alone the cost of being unprepared is rising fast.

What India Must Prepare for in a Fragmented Financial Order

Few shifts in global finance announce themselves loudly. They unfold in the margins, in trade invoices quietly settled in local currencies, in bullion reserves added gram by gram, in policy briefs that read less like strategies and more like contingency plans.

India doesn’t need to pick a side between fading hegemons or rising challengers. What it needs is to build economic institutions that don’t react to the moment, but shape the next one. That means asking harder questions: not just how to increase reserves, but how to reduce vulnerability; not just how to trade in rupees, but how to make others trust it; not just how to join new arrangements, but how to lead them with credibility.

The reality is, no global financial order lasts forever, but its end rarely looks like collapse. It looks like decisions taken at the margins: a shift in reserve allocation here, a bilateral settlement there, a quiet gold purchase, a vote in a multilateral forum. These changes seem technical, even forgettable, until they aren’t. The task for India is to be ahead of that curve, not by making headlines, but by building ballast.

Credibility in this new world will not come from GDP numbers or diplomatic speeches. It will come from whether the Indian state can be trusted to hold steady when others waver, whether it can anchor value not just through promises, but through consistency. This is not just a matter of monetary policy. It is a question of institutional maturity, political stability, and the kind of long-term thinking that outlasts electoral cycles.

The world is not desperately searching for the next dollar. It is nevertheless searching for new, alternative forms of reserve-based money systems it can rely on with credibility. The more India sees that challenge as its own, the more prepared it will be, not just for the end of something old, but for the quiet beginnings of something new-and vital.

Deepanshu Mohan is a Professor of Economics, Dean, IDEAS, and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies. He is a Visiting Professor at London School of Economics and an Academic Visiting Fellow to AMES, University of Oxford.

Ankur Singh is a Research Analyst with Centre for New Economics Studies.

This article went live on June thirtieth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-seven minutes past five in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.