Ranking Rich, Living Poor: The Fiscal Health Mirage in India’s Development Story

The recently released Fiscal Health Index 2025 has brought out some quite surprising results. The states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, often considered among India's most backward in social development, rank among the best in fiscal health. Meanwhile, states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala, known for their high social and human development indicators, are ranked lower.

This paradox raises a crucial question: Does fiscal prudence come at the cost of public welfare? Or is this data to do with the underlying political economy of possible unequal distribution as to how revenues, grants, and financial support from the central government are distributed?

At the heart of this issue is India's fiscal federalism, how revenues, taxes, and financial transfers between the centre and states shape economic and social outcomes. The rankings basically suggest that states prioritising social welfare seem to struggle with fiscal sustainability, while those with limited social investment maintain a stronger fiscal position. This raises concerns about structural imbalances in India’s fiscal framework, the role of the central government in revenue distribution, and whether states with opposition governments face fiscal discrimination.

The curious case of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh vis-a-vis Kerala and Tamil Nadu

The recently launched Fiscal Health Index 2025 highlights the unexpectedly high fiscal strength of the states of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, despite their relatively poor social indicators, weak infrastructure, and lower per capita income. On the other hand, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, which consistently rank among the top states in literacy, life expectancy, and overall human development, rank lower in fiscal health. A key factor that can explain this apparent paradox lies in examining the revenue receipts per GSDP into these respective states, their expenditures and social indicators.

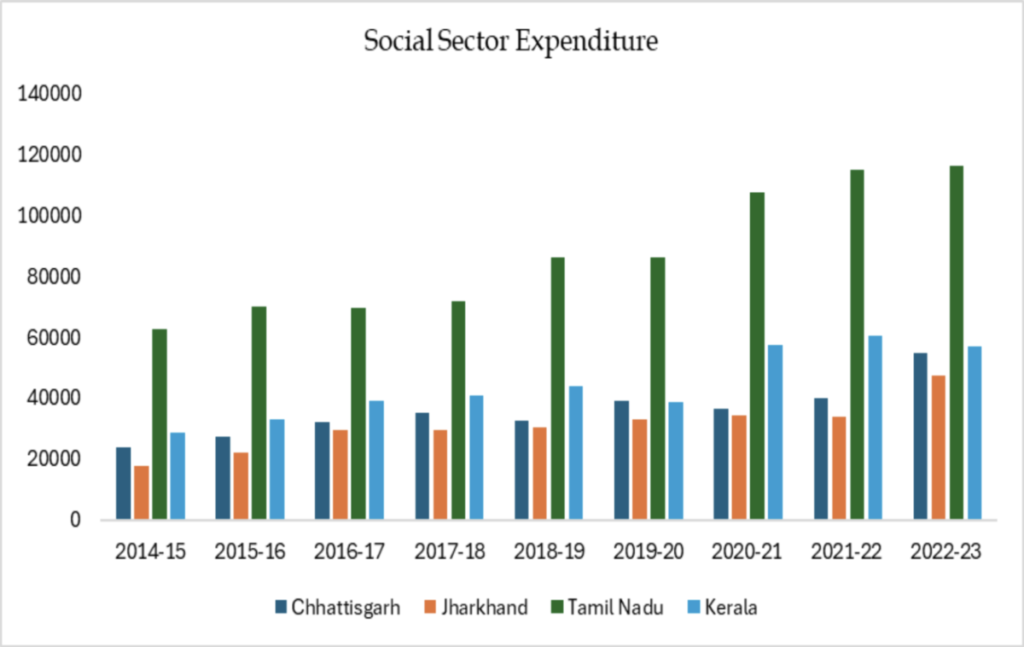

Social sector expenditure across years

Source: Handbook of Statistics on Indian States 2023-24, RBI.

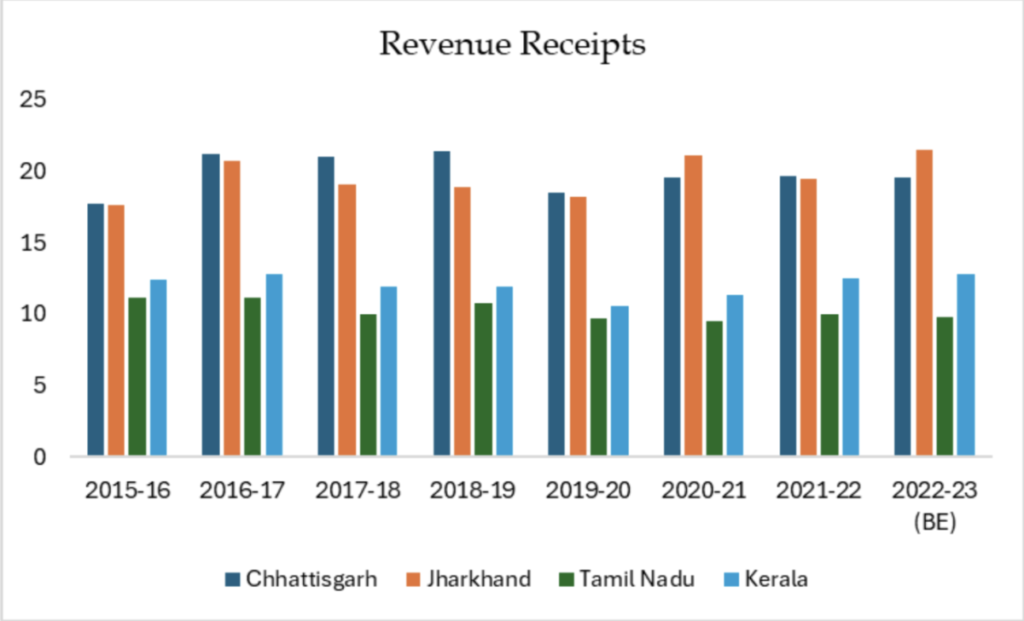

Revenue receipts per GSDP for states across years

Source: RBI’s State Finances.

Various social indicators across states

| State-wise poverty rate (2011-12 Based on MRP Consumption) in % | Maternal Mortality Rate (2018-20) | Infant Mortality Rate (2020) | Literacy Rate (2011) | Human Development Index (2017-18) (*no states in low HDI) | Social Progress Index (SPI) | Rank in SPI | |

| Chhattisgarh | 39.9 | 137 | 38 | 70.28 | Medium HDI (0.550 to 0.699 | 51.36 (Lower-middle social progress) | 28 |

| Jharkhand | 37.0 | 56 | 25 | 66.41 | Medium HDI (0.550 to 0.699 | 43.95 (Very Low Social Progress) | 36 |

| Kerala | 7.1 | 19 | 6 | 94.00 | High HDI (0.700 to 0.799) | 62.05 (Very High Social Progress) | 9 |

| Tamil Nadu | 11.3 | 53 | 13 | 80.09 | High HDI (0.700 to 0.799) | 63.33 (Very High Social Progress) | 6 |

Source: National Statistical Office and Handbook of Statistics on Indian States (RBI) and Centre for Inclusive Growth (for SPI).

To begin with, the proportion of the total tax revenue allocated to the states by the Union government is approximately 32%, which is notably lower than the 41% recommended by the 15th Finance Commission. Moreover, there is clear evidence that Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh receive higher receipts and devolution of grants from the Union government. This external financial support enables them to maintain fiscal discipline without necessitating a significant increase in their own revenues or welfare spending.

Furthermore, it is important to recognise that both states are considered mineral-rich due to high deposits of coal, iron ore, bauxite and other minerals. However, despite these advantages, both states allocate significantly lower expenditures toward critical sectors such as education, healthcare, and social security programs.

Although the social sector expenditure as a percentage of Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) was comparatively higher in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh in 2015 (6.86% and 6.96%) and 2016 (7.93% and 8.20%) than in Tamil Nadu and Kerala (2015: 5.20% and 5.13%; 2016: 4.72% and 5.70%), this increased allocation has not translated into corresponding improvements in human development outcomes. Although Jharkhand’s gross expenditure on the social sector is significantly lower than Kerala's, yet it ranks higher in fiscal stability. This suggests that this fiscal "success" does not necessarily translate into better human development outcomes. Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh rank below Kerala and Tamil Nadu on the Human Development Index, and continue to grapple with challenges like poor education, high malnutrition, weak healthcare infrastructure, and low employment opportunities.

On the contrary, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, which consistently rank among the top in literacy, life expectancy, and overall human development, are observed to fare relatively lower in fiscal health. However, this weaker fiscal standing should be examined from the lens of prevailing political dynamics and structural constraints, rather than being attributed to mismanagement. Both states have a long-standing history of substantial investments in public welfare, including universal healthcare, subsidised education, and welfare schemes. These states have consistently allocated significant resources to the social sector over years, which have been indeed translated to better outcomes in human development. Such expenditures, while contributing to fiscal deficits and debt burdens in the short term, are ultimately beneficial in the long run. While this might be considered as detrimental to fiscal stability, it is essential to note that this might be a result of inequitable and disproportionate allocation of tax receipts, transfers and grants from the centre, as well. As demonstrated in the graph above, both Kerala and Tamil Nadu receive significantly lesser transfers from the central government than the other two states, and the tax revenue is distributed far less equitably to these states than to the others.

It is also important to recognise that India’s fiscal framework is increasingly influenced by political favouritism, where the central government appears to prioritise the funding of the states aligned with its political agenda, while neglecting those that oppose it. This is particularly evident in instances of funding cuts, delays and a lack of support during unforeseen events such as natural disasters. A notable example is the Kerala floods, when the central government withheld aid and relief. Concerns regarding fiscal inequity have been frequently raised by states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala, particularly in relation to inadequate revenue devolution. This issue exacerbates the ongoing debate surrounding the North-South divide, as states that contribute significantly to India’s GDP receive comparatively lower per-capita central funding than economically weaker states.

The problem with India’s fiscal health narrative

While the Fiscal Health Index implicitly rewards states that prioritize budget surpluses, low fiscal deficits, and controlled debt levels, it overlooks a fundamental issue: What good is fiscal strength if it does not translate into better living standards? A state with a low fiscal deficit but high unemployment, poor education, and weak health services cannot be considered well-governed. Conversely, a state that invests in human capital and social security may run a higher fiscal deficit but ensures long-term economic resilience and social stability. If a state’s fiscal health is assessed solely on budgetary discipline while ignoring welfare outcomes, the rankings fail to capture the real economic reality on the ground.

Instead, it is imperative to ensure progressive redistribution of finances from the Union government to the states. India's fiscal policies should continue to prioritise long-term social development, particularly in states such as Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Though substantial financial transfers may be aimed at these states, they still lag behind in terms of social development indicators that show the need for efficient and equitable allocation of financial resources in a manner that has positive development implications in the long run. Further, what good does it bring to the state to be financially disciplined and remain fiscally "healthy" on paper while suffering from deep-rooted developmental deficits.

Additionally, the government should also take keen interest in states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, who despite leading in social indicators, may struggle with increasing fiscal constraints, which might eventually exacerbate regional inequalities. An inclusive fiscal policy framework is necessary to ensure that India’s economic success is not just about balanced budgets but about balanced development as well, where fiscal health and social well-being go hand in hand.

Aurolipsa Das and Boddu Srujana are Assistant Professors in Economics at SRM University, Andhra Pradesh.

This article went live on February fourteenth, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-two minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.