Indian Economy Is Rigged Under Plutocratic Influence. What About Elections?

A few years ago, Nobel Laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz wrote that the American economy is rigged. He argued that the US has the highest income inequality, with the top 1% accumulating disproportionate wealth compared to the rest of the 99%, whose income levels have remained stagnant. India is staging its own version of inequality theatre, with a cast of billionaires hogging the limelight while the rest of the population plays understudy.

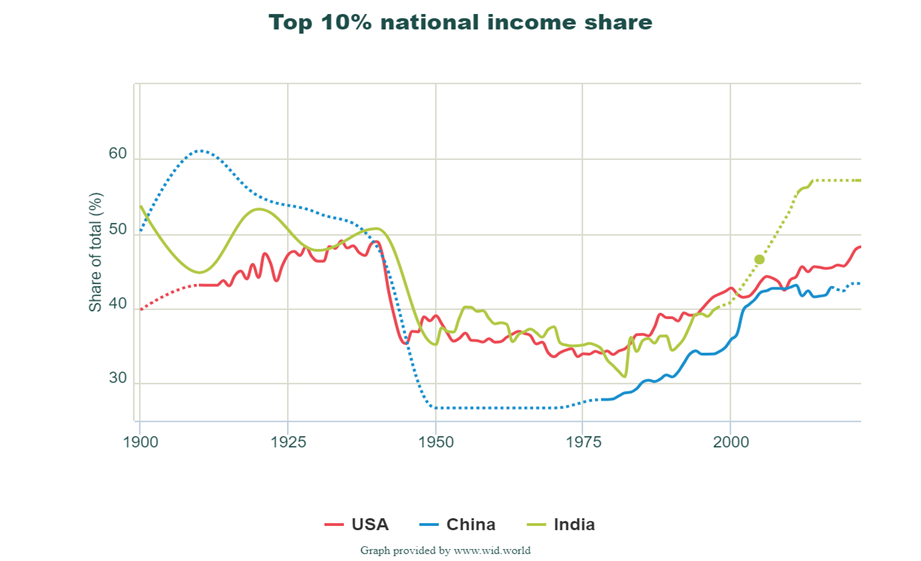

India's economy is rigged too. Yes, really. And more so than America's economy, with the top 10% having a national income share greater than that of the top 10% of either the US or China, according to data from the World Inequality Database.

However, unlike the prevalent sentiment in America where a substantial portion of the populace believes the economy is rigged against them, the discourse on this matter is conspicuously absent from the narrative in India. One could infer that its deliberate omission from discourse is a testament to the iron grip of plutocratic forces, which exercise unyielding control over the nation's political landscape, sparing no corner from their influence.

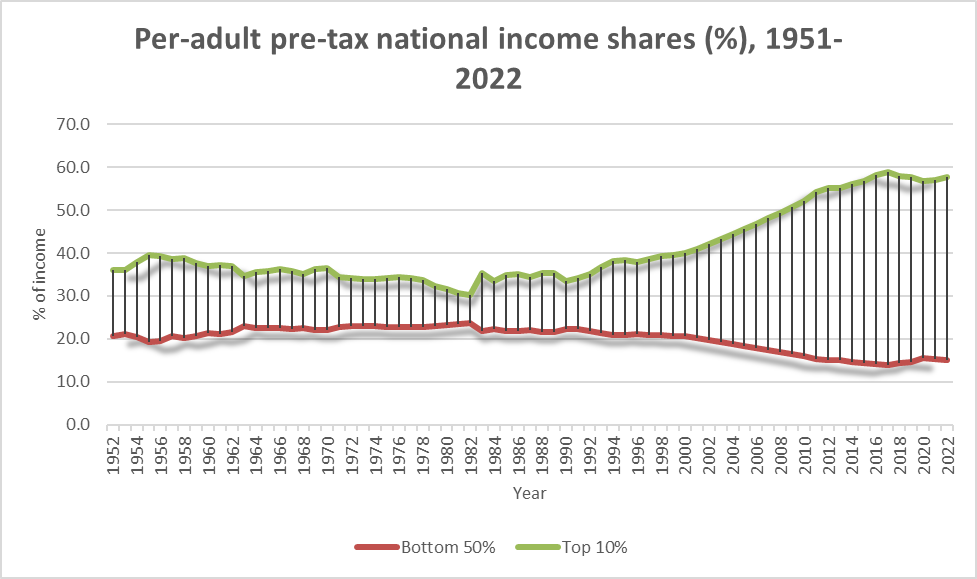

The recently released report from the World Inequality Lab provides further evidence of the accumulation of income among the top 10%, achieved by squeezing the incomes of both the bottom 50% and the middle 40%. If one analyses the pre-tax per adult income data in the report's Data Appendix series, it reveals a troubling trend of income redistribution in recent years, primarily from the middle 40% to the top 10%. For instance, in 2007, the middle 40% earned 34.5% of the total income, which decreased to 27.3% by 2022. During the same period, the top 10% saw their share of total income rise from 48.1% to 57.7%, while the share of the bottom 50% decreased from 17.5% to 15%. This data clearly shows that the top 10% gained 7.2 percentage points of income share from the middle 40% and 2.5 percentage points from the bottom 50%.

Figure 1 below illustrates how the gap between the income of the top 10% and bottom 50% has been particularly increasing in the last 12 years.

Figure 1. Source: World Inequality Lab, Data Appendix Series

The per adult national wealth shares data series, spanning from 1961 to 2022, reveals intriguing trends. In 2005, the bottom 50% owned the same proportion of wealth as they did in 2022, holding steady at 6.5%. However, during this period, the top 10% saw a significant increase from 59.7% to 64.6%, representing a 4.9 percentage point rise, largely at the expense of the middle 40% bracket.

In 1961, the bottom 50% owned 11.4% of national wealth, while the top 1% and top 0.1% held 12.9% and 3.2%, respectively. Fast forward to 2022, and the top 0.1% has seen a disproportionate increase of wealth by nine times.

Furthermore, while the top 1% and bottom 50% began from relatively similar bases in 1961, their wealth ownership has diverged significantly over time, leading to the emergence of a Y-shaped forked curve, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Source: World Inequality Lab, Data Appendix Series

Beware of the undercover wolves!

“Poverty is India’s biggest caste,” we are told. Yet, when economists and government officials hastily assert that poverty has fallen to just 5%, they inadvertently poke holes in the very doctrine championed by their leaders, who proclaim poverty as the "biggest caste" in the nation.

'Wealth redistribution is no cure to economic inequality;' 'Inequality is a natural outcome of market forces;' 'Income inequality isn’t a major problem” – All these myths are regularly floated in the media usually propagated by some boisterous news anchors and some usual proponents of the establishment.

In their zeal to discredit the idea of redistributing wealth in favour of the impoverished, they conveniently turn a blind eye to the blatant reverse wealth redistribution favouring the affluent.

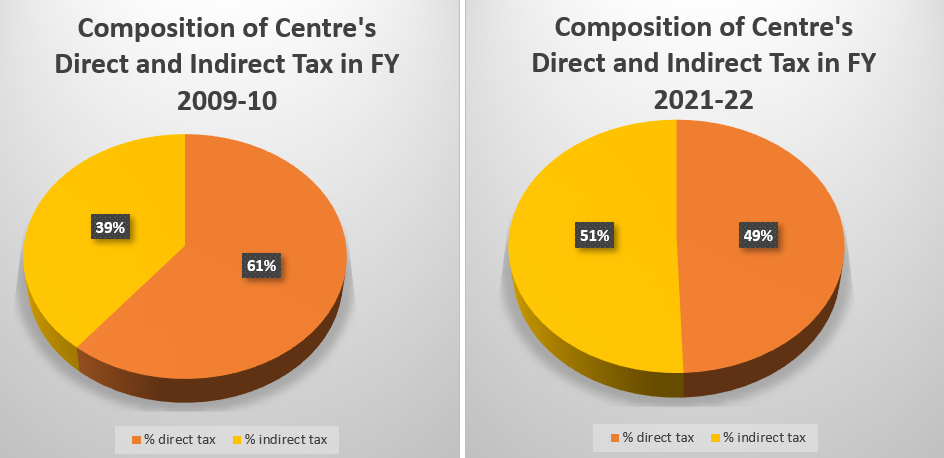

Ask this: What does a government do? It collects taxes and spends them. If we consider the taxation policy and expenditure pattern, there have been broad paradigm shifts on both fronts, often to the detriment of the poor in this country. Let’s consider taxation: In 2009-10, 61% of the total tax collected was direct tax, and 39% was indirect tax. In 2021-22, direct tax contributed approximately 49%, while indirect taxes contributed 51% to the total tax collection.

This is inherently wrong and downright regressive. A more just policy should imply that the weight of taxation should fall upon the broad shoulders of the wealthy, not the strained backs of the working class. In fact, the government has been practising the reverse, penalising the poor and middle class to subsidise the rich.

According to an Oxfam report, nearly two-thirds of indirect tax comes from the bottom 50%. That means it is the poor person who is being forced to pay, so that the government can give corporate tax cuts, like the way it did in September 2019.

Figure 3. Source: RBI Handbook of Indian Statistics on Indian Economy

Let’s consider the expenditure pattern of the Union government.

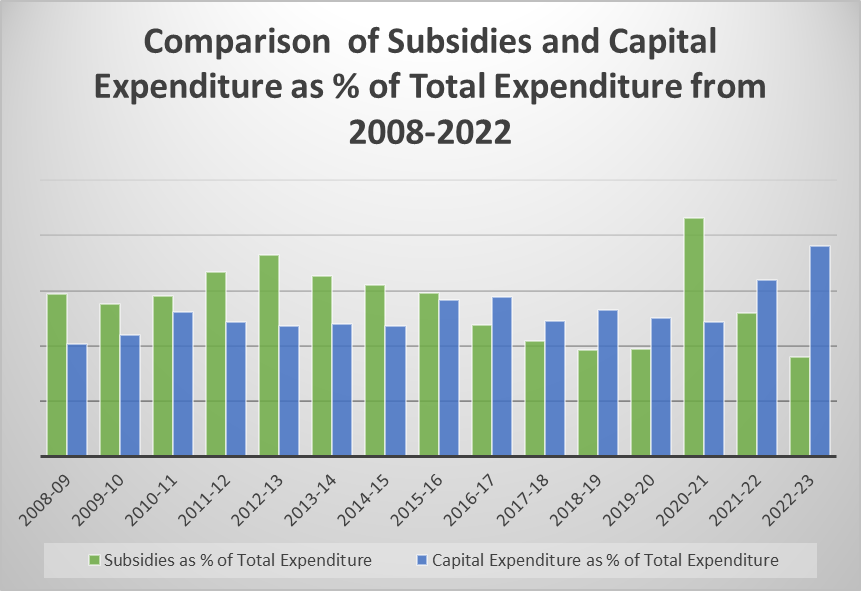

The Government of India spends on three major heads: capital expenditure, subsidies (part of revenue expenditure), and defence and national security. A just approach would prioritise subsidies over capital expenditure for wealth to trickle up and not trickle down. But the Union government did exactly the reverse.

Since 2016-17, except for the COVID-19 year, there has been a remarkable increase in capital expenditure, often occurring at the detriment of subsidies, thereby defying the principles of equitable resource distribution. Capital expenditure predominantly serves corporate interests as it involves investments in infrastructure projects that often yield profits for corporations. These projects, such as constructing roads, railways, ports, and airports, not only enhance transportation and logistics but also open up opportunities for private sector involvement. Corporations frequently undertake these projects to facilitate their operations, expand their markets, and increase their profitability.

On an average, from 2008-09 to 2013-14, the government spent 15.7% of total expenditure on subsidies for the poor, and 11.7% for capital expenditure. Contrast that with the period spanning from 2014-15 to 2022-23 where the average spending on subsidies is 12.8% and the average spending for capital expenditure is 13.9%. Evidently, the reduction in subsidies went to augment capital expenditure and other heads of government spending like defence and interest repayment.

Figure 4. Source: RBI Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy

Every day, the rules of the economic game are sneakily rewritten, consistently favouring the wealthy while leaving the poor at a distinct disadvantage.

Is India's staggering inequality a direct consequence of the globalisation policies initiated in 1991? If so, then why does India's inequality surpass that of nations that embraced economic liberalization much earlier?

The grim truth is that government intervention plays a pivotal role in combating inequality in any nation. However, in India, governmental actions are exacerbating the already severe inequality dilemma through regressive taxation policies and egregiously skewed expenditure patterns that overwhelmingly benefit the affluent.

It almost seems like there is preordained agenda to rob Peter and pay Paul, perpetuating the cycle of economic rigging with a sly wink to those indirectly pulling the strings.

Also read: Who Were the Top Buyers of Electoral Bonds Paying?

The mouse and the mountain

The corporate hijack of our polity has begun. In a capitalist society like ours, power invariably flows to where money resides. Elections, theoretically a platform for democratic expression, have regrettably devolved into auctions where victory is purchased by the highest bidder. We've surrendered our voting autonomy to the dictates of corporate titans. Yet, can we be held entirely responsible?

Information, as Arundhati Roy astutely observed, has transmuted into a "poisoned chalice." Our voting pattern has been systematically manipulated, rendering us complicit in our own disempowerment.

Consider the insidious weaponisation of money through electoral bonds – an unprecedented un-equalizer of democracy. This has birthed a towering behemoth of cash, an unmatched juggernaut, crushing the voices of the marginalised beneath its weight. We've allowed a tsunami of capital to drown out the cries of the disenfranchised, perpetuating an abyss of inequality and injustice. Suppression is at times wielded with dictatorial intent to ruthlessly mold the collective voting consciousness. The usurpation of institutional autonomy, and its subsequent weaponisation to arrest a sitting chief minster, to conduct raids in the houses of MPs, to starve the largest opposition party of financial resources are all part of this larger project which is to mold the collective voting consciousness.

In a democracy like ours, money inevitably becomes the biggest tool of both political expression and suppression. Rigging an election isn’t only about tampering with the voting process; it includes stifling these essential elements of democracy. The unassailable importance of democracy extends beyond mere voting, and the credibility of elections relies on factors beyond the simple act of casting ballots.

Without reservation, it can be argued that the essence of democracy encompasses aspects beyond the ballot box, and the integrity of electoral processes encompasses more than just the act of voting. Given the rigged nature of our economy, plutocratic forces have effectively seized control of the mainstream media and political sphere, consolidating their influence by monopolising information channels (including social media) and frequently weaponising them to oppress the impoverished through the dissemination of vicious narratives, consequently lacerating our people to think critically.

Let's call it what it is: The mandate of the 2024 General Election is unlikely to truly represent the democratic expression of the poor in this country. It has been insidiously rigged even before the electoral process has begun. And what can they do about it?

But let us not talk about the poor. Let us not say that the economy is rigged against them. Let us not say that the election is already rigged. Let us say, “God’s in his Heaven – All’s right with the world!” Let us close our eyes on the poor and Move On!

Snehasis Mukhopadhyay is a data science enthusiast with a penchant for drawing insights from political economy.

This article went live on March twenty-eighth, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.