India's Job Market: A Statistical Conundrum with Underlying Concerns

This is the fourth part in a special series by the Centre for New Economics Studies’s InfoSphere team which aims to closely study and understand the macro-state of the Indian economy in a lead up to the next Union Budget. Read part one here, part two here and part three here.

India's job market landscape presents a complex narrative, characterised by both positive indicators and underlying anxieties. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently published 'Measuring Productivity at the Industry Level-The India KLEMS [Capital (K), Labour (L), Energy (E), Material (M) and Services (S)] Database' providing data on employment trends across 27 key industries in India. The database, spanning 1980-81 to 2022-23 aims to provide critical data points on economic output (GVA and GVO), worker skill levels (Labour Quality), capital investment (Capital Stock), and productivity measures (Labour Productivity and Total Factor Productivity).

On a preliminary analysis, data from the KLEMS database suggests a job creation surge in India. The picture presented seems rosier than ever for the government’s underwhelming performance on employment creation so far. According to the database, the economy witnessed the addition of nearly 4.67 crore jobs in FY 2023-24, reflecting a robust 6% growth rate. Consequently, the total number of employed individuals in India climbed to a substantial 64.33 crore. This positive trend appears to be supported and objectively created to suit the government’s rhetorical narrative on employment, indicating the creation of over eight crore jobs between 2017-18 and 2021-22, averaging two crore jobs annually.

However, a more meticulous examination reveals potential discrepancies within this seemingly optimistic picture.

Concerns regarding the quality and long-term sustainability of these newly created jobs persist. A report by Citibank warns that a 7% GDP growth rate might only create a modest eight-nine million jobs annually over the next decade. This falls short of what's needed to absorb India's ever-growing workforce. This discrepancy between government data and Citibank's projections raises concerns about the job market's ability to keep pace with the growing number of job seekers.

Further concerns arise when we consider the quality of these jobs. The seemingly low 3.2% unemployment rate might be misleading. A much higher youth unemployment rate (16%) suggests a mismatch between job quantity and quality. Many new jobs could be low-paying or lack opportunities for growth, contributing to underemployment, where people are technically employed but their jobs don't fully utilise their skills or offer financial security.

India's job market: A cause for concern?

Adding to the concerns is the recent rise in unemployment. Unlike the 7.5-7.7% rate in the previous two years, 2023-24 saw unemployment climb to a concerning 8%. This translates to nearly 37 million people actively seeking jobs, a number not seen since the pandemic's peak. While the March 2024 quarter saw a slight dip to 7.5%, the overall year-end figure remains high.

The situation is further highlighted when compared to pre-pandemic years. The average unemployment rate for 2016-23 (excluding the pandemic year) was around 6.8%. While the pandemic caused a temporary spike (8.8% in 2020-21), the current rate of 8% remains worrying. The number of unemployed individuals looking for work has also increased from 33 million in 2016-17 to 36.9 million in 2023-24.

Figure: Unemployment Rate (Source : CMIE)

While the absolute number of employed individuals has increased (from 412.7 million in 2016-17 to 423.3 million in 2023-24), this translates to a meagre 2.6% growth over seven years. This is because the working-age population has grown at a much faster pace. In simpler terms, job creation hasn't kept up with the growing number of people seeking employment.

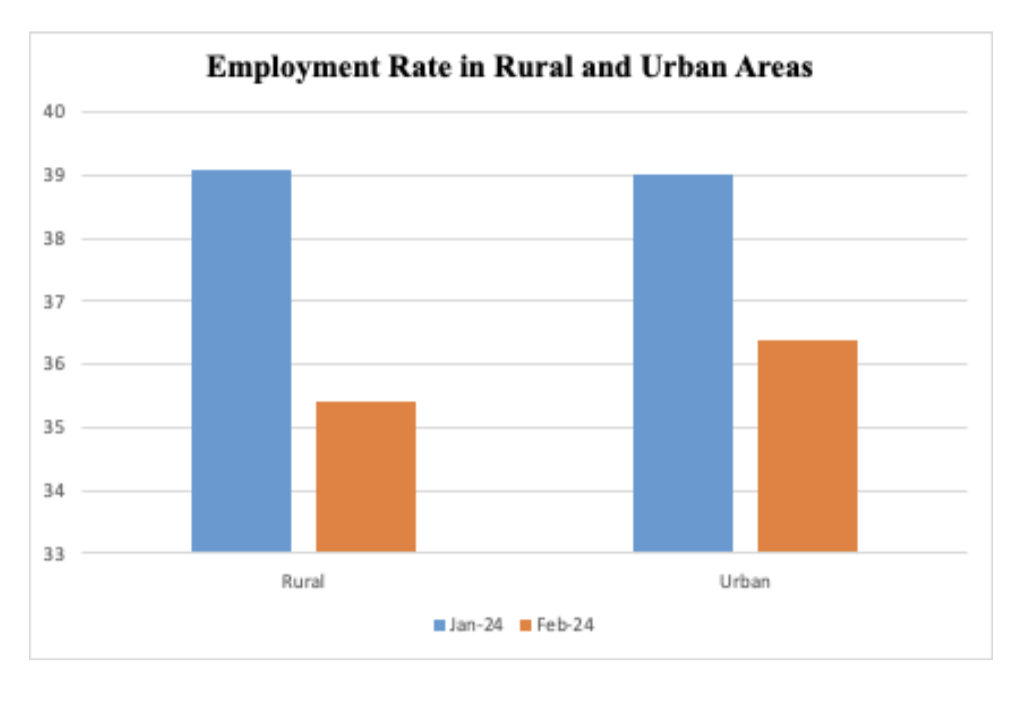

The rural-urban divide: A concerning trend

The positive national employment figures mask a concerning disparity between rural and urban areas. While the overall unemployment rate has dipped to a 20-month low of 7%, data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) reveals a surprising trend. Rural areas are experiencing a decrease in unemployment, leading the national average down. However, this decrease might not be entirely positive.

Figure : Employment Rate in Rural and Urban Areas (Source: CMIE)

A closer look at rural employment reveals a disquieting trend. Despite rising overall employment rates, agriculture remains the dominant employer, with nearly half the rural workforce (46%) relying on a sector contributing less than 20% to GDP. The agriculture and allied industry saw a nominal year-on-year growth of 1.9% and employed 25.3 crore individuals in 2022-23.

Figure: Number of persons employed in Agriculture, Hunting, Forestry and Fishing (Source: RBI KLEMS)

This dependence on agriculture is particularly concerning for women, who make up a significant portion (76.2%) of agricultural workers. Experts attribute this shift back to agriculture to the pandemic's impact, which has led to a rise in self-employment, unpaid work, and stagnant wages in the sector. Data suggests that while the labour force participation rate has increased and unemployment has declined, the nature of employment in rural areas doesn't necessarily indicate healthy growth.

Furthermore, a 14.3% year-on-year decline in MGNREGA employment in May 2024 highlights the challenges in creating sustainable alternatives for rural employment.

This situation underscores the need to move beyond just the number of jobs created in rural India. Focusing on skilling the workforce for opportunities beyond agriculture and promoting rural entrepreneurship are crucial steps towards building a more diversified and secure employment landscape.

Data for February 2024 further illustrates the rural-urban divide. While a substantial share of people who entered the labour force in urban areas found jobs, a significant number in rural areas joined the unemployed pool, leading to an increase in the rural unemployment rate.

Although both rural and urban India saw an increase in labour force participation in February, the picture regarding job creation differed. Urban India fared better, with the urban employment rate reaching 36.4%, the highest since February 2020 (pre-pandemic levels). This indicates that not only did new entrants find jobs, but some previously unemployed individuals were also able to secure employment. Consequently, urban unemployment fell to 8.5%.

Conversely, the rural workforce shrunk in February, leading to higher unemployment. The rural employment rate dropped,and the unemployment rate spiked by two percentage points to 7.8%. This highlights the struggle of rural areas to recover pre-pandemic employment levels. While urban employment has bounced back, rural employment remains below 40%, the pre-pandemic norm.

Shifting composition of the workforce

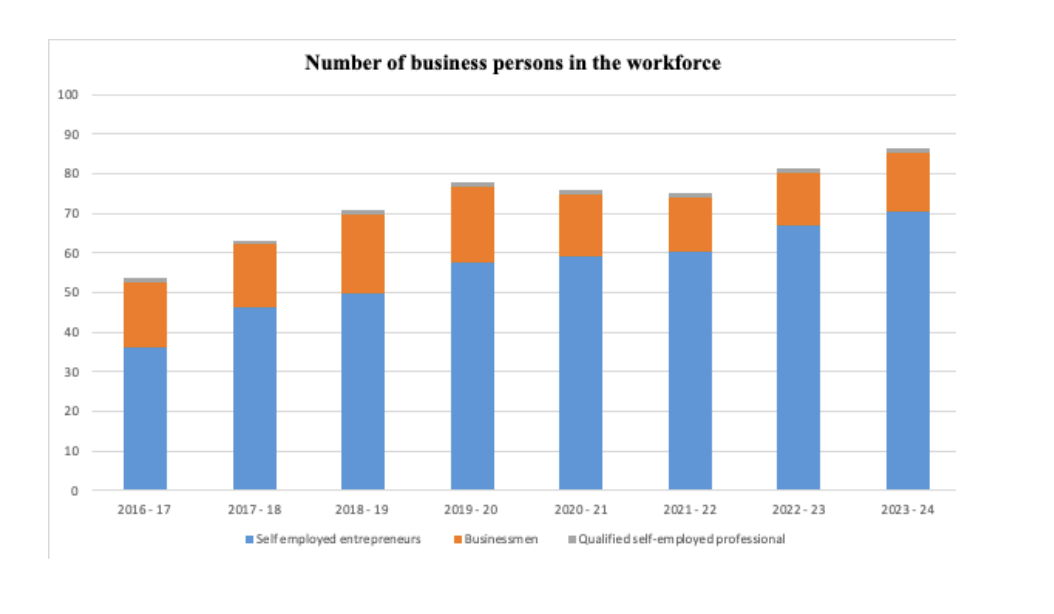

The increasing dominance of self-employment paints another layer on the complex picture of India's job market. Data from CMIE's Consumer Pyramids Household Survey reveals a steady rise in self-employment across both rural and urban areas. In 2022-23, 57.3% of employed individuals were self-employed, compared to 55.8% and 55.6% in the previous two years. This marks a significant rise from the pre-pandemic figure of 52% in 2018-19.

This trend aligns with a broader shift in India's workforce composition. Back in 2016-17, only 13% of employed individuals were categorised as "business persons" by CMIE. By 2023-24, this figure had surged to nearly 20%, highlighting the significant rise in self-employment. The total number of employed business persons reached a staggering 86.6 million in 2023-24.

Figure: Number of business persons in the workforce

The composition of "business persons" has also undergone a significant transformation. The share of businessmen, traditionally managing larger businesses with substantial resources, has shrunk dramatically from 30.3% in 2016-17 to 16.7% in 2023-24. This decline is offset by the surge in self-employed entrepreneurs, whose share has risen to 81.5% in the last fiscal year. Qualified self-employed professionals like doctors or lawyers, however, remain a tiny fraction (below 2%) of all "business persons."

The substantial increase in self-employed entrepreneurs (from 36.1 million in 2016-17 to nearly 70.6 million in 2023-24) is noteworthy. However, the question arises whether this growth reflects genuine entrepreneurship or simply a response to limited job opportunities. The concentration of new jobs among self-employed entrepreneurs, particularly in app-based sectors, suggests a potential bias towards less secure, informal employment. Additionally, the stagnation in "better quality" jobs like businessmen and qualified professionals raises concerns about the overall quality of job creation in India.

Also read: Dear FM, Corporate Revenue Foregone in 5 Years is Nearly Rs 8.7 Lakh Crore, Where are the Jobs?

In conclusion, India's job market analysis reveals a complex interplay of positive headline figures and underlying anxieties. While job creation appears better than before, youth unemployment still remains high combined with heightened rural disparity. Further, The quality and long-term sustainability of these ‘new’ jobs are uncertain, necessitating a closer look at job security and in addressing informality.

Moving forward, in the upcoming budget, more direct fiscal interventions towards incentives for labour intensive manufacturing, or in boosting employment-creating sectors, skilling the workforce, promoting rural entrepreneurship, and prioritising high-quality job creation are needed. These are critical steps towards a more balanced and inclusive job market for India. Unfortunately, the government and its lobbying network of policy intellectuals are more focused on cooking data than recognising what it is-to address the problem in the first place.

Deepanshu Mohan is professor of Economics, dean, IDEAS, Office of Interdisciplinary Studies, and director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), O.P. Jindal Global University. He is a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and a 2024 Fall academic visitor to the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford.

Aditi Desai is a senior research analyst with CNES and lead of its InfoSphere initiative.

This article went live on July twenty-second, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.