Necessary Reforms, Missed Opportunities: The Troubled Rollout of India’s Labour Codes

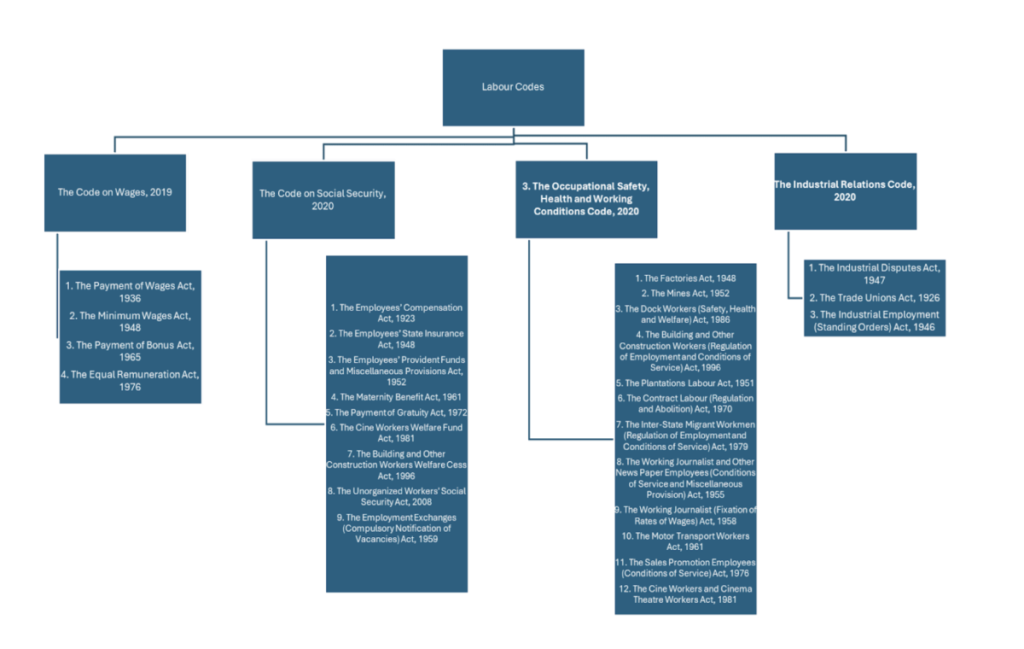

India’s labour laws have long been a maze, an unwieldy tangle of 29 central statutes, hundreds of state amendments, conflicting definitions, and overlapping jurisdictions. Till just over a decade ago there were 45 labour laws (in addition to over 100 states ones taken together), until some were repealed. For decades, labour economists, industry associations, and reform commissions agreed that this fragmented architecture served neither workers nor enterprises well. The Second National Commission on Labour had recommended as early as 2002 that India move toward four or five comprehensive codes to replace the old system. Two decades later, parliament finally enacted that vision through the four labour codes on Wages, Social Security, Industrial Relations, and Occupational Safety and Health – though only to replace the Union government’s laws.

The merger of 29 central laws into just four codes reduced the rules from nearly 1,400 to roughly 350, and cut the number of returns and forms by around half. The codes also collapse multiple overlapping definitions of “worker”, “wages”, and “establishment” into unified, standardised definitions, aiming to remove long-standing ambiguity that has plagued both employers and workers.

Yet the path from legislative consolidation to real-world reform may prove far more tumultuous than anticipated. The sudden notification of all four codes on November 21, 2025 has triggered anxiety among workers, unions, employers, and state governments. As things stand, labour codes’ reform has been to modernise the outdated legal system, but largely to address the demands more from an employer's perspective than a worker's lens.

Why reform was inevitable

India’s labour market realities made the old legal regime (which had evolved in early decades post Independence when the expectation was that most new employment will be in the organised, not unorganised, sector) increasingly untenable. Over 90% of India’s workforce continues to work in the informal economy, and informal enterprises contribute almost 45% of GDP . Even today, around 120 million people work in the non-agricultural informal sector, mostly without social-security coverage.

Even after the recent labour codes’ implementation they would not apply to 85% of workforce of India that is unorganised in nature. There were many factors underlying the small size of Indian enterprises (relative to other countries at the same level of development); among them were the complexity of labour laws: multiple thresholds for applicability, inconsistent wage definitions, and varied inspection regimes – which deterred formalisation and kept enterprises small.

What the Codes aim to do

The Codes on Wages (2019), Social Security (2020), Industrial Relations (2020), and Occupational Safety and Health (2020) were crafted to bring order to this chaos. They consolidate the erstwhile laws into a unified framework, rationalise definitions, reduce compliance redundancies, and set the foundation for technology-driven governance.

The Wage Code merges four laws, establishes a national floor wage and standardises wage definitions to prevent employers from splitting wages into allowances to evade provident-fund or gratuity contributions.

The Social Security Code merges nine labour laws and attempts to universalise benefits well beyond the formal workforce. Notably, it recognises gig and platform workers an emerging labour category in India’s digital economy and extends gratuity to fixed-term workers.

The OSH Code merges 13 laws governing safety and working conditions across factories, mines, plantations, and other establishments. Meanwhile, the Industrial Relations Code reorganises three laws and reforms dispute resolution, increases the retrenchment threshold from 100 to 300 workers, mandates a 60-day notice for strikes, and introduces a “negotiating union” system based on majority membership.

Apart from consolidation, the underlying promise of these codes is that a simpler legal framework will improve compliance, encourage formal employment, and reduce litigation emerging from contradictory provisions in older laws.

A labour market under stress

The timing of the codes is not accidental. India’s labour market is undergoing structural change. PLFS data show rising urban employment, declining rural employment, and a shift toward informal service-sector jobs. A majority of the workforce remains self-employed or in casual work, with women and young people disproportionately occupying low-quality jobs.

In this context, the government has sought to create a unified social-security framework. The e-Shram portal, launched in 2021, now has over 30 crore registrations – nowhere close to the 55 crore or so informal workers in India’s total workforce of 61 crore (2024). But registration alone does not guarantee benefits. Most workers on the portal still receive no additional entitlements; instead, they are nudged toward applying separately for a dozen uncoordinated schemes. The formation of an unorganised workers social security board is a step in the right direction but without financing put in place this may not lead to implementation, as was the case with Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008.

Even in the Social Security Code, the inclusion of gig workers is commendable and recognising gig and platform workers in the category of workers would help in safeguarding lakhs of workers. The gap between data-driven visibility and actual security remains one of the most significant challenges that the Social Security Code must address. Without functional integration between central and state systems, and without portable, enforceable entitlements, universal social security will remain an aspiration. However, the fact is that in a SS Code of over 100 clauses barely two clauses are devoted to the unorganised sector workers, although they constitute 85% of all workers.

The biggest problem in India’s labour market that the four Codes fail to even touch, let alone address is: the entire labour law barely covers the unorganised sector of India’s enterprises, which account for 85% of India’s 73 million non-farm enterprises. In other words, the labour law regime was, and still is, confined to protecting workers in the organised sector. Even there they tend to raise concerns, which we now turn to discuss.

Where the codes raise concerns

While the codes simplify legal architecture, certain provisions have triggered deep apprehension among labour unions, researchers, and civil-society organisations. First, the decision to raise thresholds for factory coverage (especially critical for formal manufacturing) from 10 to 20 workers risks excluding millions more employed in micro-units precisely where safety violations are often most severe .

Second, the Industrial Relations Code’s expansion of the retrenchment threshold, combined with mandatory notice periods for stress, shifts bargaining power more decisively toward employers. Many fear that this will accelerate the trend toward temporary, outsourced, and fixed-term work, diluting job security.

Third, the codes also replace surprise inspections with prior intimation, which may reduce harassment but risks weakening enforcement especially in hazardous industries such as chemicals, construction, and mining.

The labour inspection regime was already extremely anaemic in India. Which country which was serious about labour rights and their implementation, would have, for a workforce of 61 crore, barely 3,000 labour inspectors across the country, for the states and centre taken together?

Impact on workers and employers

The impact of these reforms is complex. On one hand, employers benefit from clearer definitions, simpler compliance, and greater flexibility in workforce management. On the other hand, workers face the prospect of increased precarity unless enforcement is strengthened, social-security entitlements are made real, and safety standards are rigorously upheld. Even though it is difficult to summarise all the changes which has been done by authors in another longer work, the table below summarises the major impact on workers and employers of major revised provisions under the four labour codes.

Table: Impact of major changes on workers and employers

| Labour Code | Major Changes | Impact on Workers | Impact on Employers |

| Code on Wages, 2019 | National Floor Wage introduced | Sets absolute minimum wage but may be lower than state-set wages | Simplifies wage compliance but increases base salary obligations |

| Reduction in multiple wage definitions | Easier for workers to understand wages | Reduces complexity in wage calculation | |

| Inspector-cum-Facilitator introduced | May not lead to better compliance without more labour inspectors | Allows employers to rectify violations before prosecution | |

| Code on Social Security, 2020 | Fixed-term employment introduced | Fewer permanent jobs, leading to job insecurity but parity with permanent workers | Flexibility to hire and fire but requires ESI & PF contributions |

| Gig & platform workers included | Expands worker coverage | Additional compliance burden | |

| Unorganized workers Board | All unorganized workers to be registered; follow-up action unclear | Lead to formalization and contractualization | |

| Gratuity for fixed-term workers | Benefits short-term workers | Increases financial liability for employers | |

| OSHWC Code, 2020 | Factory coverage limit raised (10 to 20 workers) | Excludes small factory workers from safety laws; unorg sector was already excluded | Reduces regulatory burden on small units |

| No surprise inspections | Weakens enforcement of safety norms | Employers receive prior notice, reducing compliance stress | |

| Primary responsibility for welfare shifted from contractor to employer | Stronger protection for contract workers | Increased responsibility for principal employers | |

| Industrial Relations Code, 2020 | 60-day notice for strikes | Makes striking legally difficult, weakening worker rights | Provides time to prepare for strikes |

| Retrenchment limit raised from 100 to 300 workers | Easier layoffs, reduces bargaining power of workers | More flexibility in workforce management | |

| Sole negotiating union (51% rule) | Limits smaller unions' influence | Employers have clearer negotiation process |

Source: Authors' own compilation

A shaky implementation landscape

Perhaps the most serious challenge lies not just in what the codes say, but also in how they are being implemented. Labour is a concurrent subject, and the codes can function only when states notify their own rules, align digital systems, and retrain enforcement officials. Several states particularly those not aligned with the ruling party at the Centre have been slow or reluctant to finalise rules.

As a result, on the day the codes were notified, many states had not completed pre-publication or final notification of rules. Labour departments lacked updated registers, employer-portal integration was incomplete, and new dispute-resolution bodies were not ready to handle cases.

This creates a troubling possibility: old laws may have been repealed while new rules are not yet functional, leaving a legal vacuum. Both employers and workers may find themselves unsure of procedures, rights, or recourse. Enforcement could stall entirely, while litigation could rise sharply. India’s legal system is already jammed with pendency of cases, largely due to government being the biggest litigator – itself reflective of how incompetent are the officials running India’s State; merit in recruitment to India’s state bureaucracy is determined by passing exams and memory, not any domain knowledge in any field.

The uneven readiness of states cannot be viewed purely as administrative inefficiency. Labour unions across the political spectrum except the ruling party’s affiliated union (BMS) have opposed the codes for years. Nine central unions have labelled the reforms “anti-worker” and called for their repeal. The protests and marches on November 22 and 26, 2025, including copy-burning of the Codes, reflect the scale of this mobilisation .

Opposition-ruled states, mindful of labour sentiment and wary of a farm-laws-style backlash, have moved cautiously. Some fear that premature implementation could ignite broad-based agitation, particularly in industrial states with strong unions. Even though central labour ministry have given time till April 1, 2026 to states to prepare for the changes and republish central rules in another 45 days but the road to this change is still shaky.

This political contestation adds another layer of uncertainty to the implementation timeline. If states choose divergent models of enforcement or introduce significant variations in rules, India could end up with a fragmented regulatory landscape precisely what the codes aimed to fix.

Workers’ distrust and the sequencing problem

For workers, the pain point is not the principle of reform but its sequence. Over the last several years, they have encountered repeated drives for Aadhaar linkage, registration on the e-Shram portal, and data collection by welfare boards yet these processes have not led to reliable benefits. Many informal workers have grown sceptical of reforms that begin with administrative requirements while postponing the delivery of tangible gains. Long procedures and multiple portal registrations not leading to disbursement of welfare schemes have grown distrust among large unorganised section of the workforce.

With the labour codes, this distrust is amplified. Provisions that expand employer flexibility such as higher retrenchment thresholds (already notified in 19 states) or fixed-term employment (notified in 25 states) are immediately enforceable. But provisions promising extended social security depend on future schemes, ‘digital integration, and state-level rule-making are not. Without the Indian state even beginning to erode the distinction between the informal and formal workers – itself a reflection of India’s highly segmented caste-riven society and its mirror found in our deeply segmented education system – no amount of tinkering with the labour laws will build the ‘fraternity’, let alone ‘equality’, that India’s Constitution makers had envisaged.

Unless governments deliver early and concrete benefits such as a portable, unified social-security account linked to e-Shram, unified labour interface for disbursing social security benefits or targeted OSH enforcement in hazardous sectors the perception that reforms are “asymmetric” will deepen.

What a more orderly transition requires

A smoother rollout of the codes demands a calibrated strategy rather than a one-shot implementation. The following elements are essential:

- Clear transitional guidance: States and the Centre must issue unified guidance clarifying exactly which provisions apply, how legacy cases will proceed, and what employers and workers must do during the transition.

- Digital integration: Portals for registration, returns, inspections, and benefits must be aligned with e-Shram. Without integration, workers will face duplicate processes and employers multiple compliance platforms.

- Capacity building: Inspectors-cum-facilitators need training in risk-based inspections, advisory functions, and digital tools. Their numbers need to double in the next three years, and then double again in the following five years. Dispute-resolution bodies must be staffed and equipped before caseloads rise.

- Tripartite dialogue: Consultation with unions, employers, and civil society is essential to avoid surprises, address fears, and build trust especially in non-BJP states or labour-sensitive industries.

A phased, transparent approach can prevent the codes from spiralling into conflict and instead anchor them in institutional legitimacy.

Necessary reform, precarious execution

India’s labour codes represent a bold attempt to rewrite the rules governing work in a country where informality is the norm. They simplify a chaotic legal regime, extend social security to new categories of workers, and promise greater clarity for employers. They also reflect a genuine desire to modernise the world of work in an economy aspiring to sustained growth.

Yet the codes arrive in a context where administrative capacity is uneven, political consensus is weak, and worker trust is fragile. Without careful sequencing, synchronised state action, and visible early benefits, the reforms could trigger confusion and unrest instead of the intended clarity and protection.

The next several months will determine whether India’s labour codes become a foundation for inclusive, productive growth or another chapter in the country’s long struggle to balance flexibility with fairness.

India needs a modern labour law regime in what should become a unified labour market (almost eliminating the informal-formal distinction, both between enterprises as well as workers) in the ever-growing non-farm sector. This is a prerequisite to India become Viksit Bharat – that offers real ‘vikas’ for every citizen, not just for the organised sector units and workers. That means realizing the promise of the equality and fraternity that our Constitution promised its citizens.

Harshil Sharma is a labour economist and has a PhD from JNU. Santosh Mehrotra, Labour Economist, Research Fellow, IZA Institute of Labour Economics, Brussels.

This article went live on December second, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-eight minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.