The State Within India’s Corporate Bond Market

Over the past decade, India’s bond market has quietly evolved from a niche domain into a critical conduit of corporate finance. From Rs. 4.4 trillion in gross issuance in FY2015 to an estimated Rs. 11.2 trillion in FY2025, the segment has expanded at a compound annual growth rate of nearly 10%. But beneath this encouraging headline growth lies a more complex story: one of market concentration, implicit State subsidies, and emerging fiscal risks.

Today, almost a quarter of India’s incremental commercial credit is accessed through bond issuance, a shift driven in no small measure by the burgeoning scale of institutional investors such as mutual funds, insurers, and pension funds. With capital surpluses to deploy, these investors have become key anchors in the domestic debt market, seeking long-duration, high-quality assets.

Yet, for all the expansion, the Indian corporate bond market remains heavily skewed – both in terms of the profile of issuers and the pricing dynamics at play. More than 80% of bonds by volume are issued by entities rated AA or above, a concentration that underscores the market’s reliance on a relatively small universe of creditworthy borrowers.1

Among this elite group, a single class of issuer looms particularly large: Central Public Sector Undertakings (CPSUs). These State-controlled enterprises – ranging from infrastructure lenders and power financiers to railway funding arms – have emerged as dominant players in the bond market. Over the past five fiscal years, CPSUs have consistently accounted for over one quarter of all gross bond issuance in India, even after excluding public sector banks from the analysis.

While these entities typically boast AAA ratings and secure funding at highly competitive rates, the underlying strength of their balance sheets often tells a more nuanced story. A close examination reveals that these ratings – and the associated yield advantages – are more a reflection of implicit sovereign backing than of intrinsic credit quality. Ratings agencies themselves are explicit in this regard, routinely citing government ownership as the principal anchor of their assessments, even when the bonds carry no explicit sovereign guarantee.

This phenomenon, while ostensibly benign, carries significant consequences. It creates an unrecognised fiscal contingency for the central government, distorts risk pricing, and – perhaps most importantly – crowds out private sector issuers who lack such implicit support. As India seeks to deepen its capital markets and mobilise long-term finance for development and energy transition goals, such distortions may prove increasingly problematic.

A decade of ascent, shadowed by concentration

The decade-long expansion of India’s corporate bond market mirrors global trends in disintermediation, as borrowers tap directly into capital markets rather than relying solely on bank lending. Institutional investors – particularly mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds – have driven this shift, drawn by the promise of stable yields and regulatory flexibility.

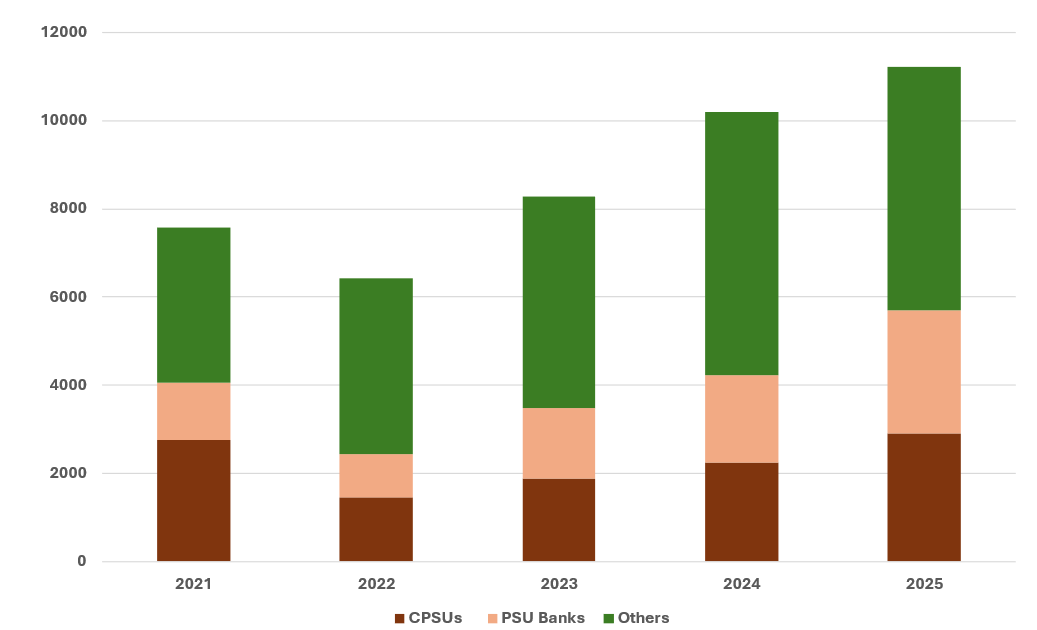

Figure 1. Corporate bond issuance in India (billion Rs.)

Source: NSDL, Prime Database.

Yet, the growth in issuance volumes masks two structural characteristics. First, the market is overwhelmingly skewed toward high-rated borrowers. Over 85% of issuances in the past decade have carried ratings of AA or higher, leaving sub-investment-grade and mid-tier corporates largely dependent on traditional lenders. Second, CPSUs – and to a lesser extent, public sector banks – have come to dominate the issuance landscape. Collectively, they accounted for 45% of total corporate bond issuance between FY2021 and FY2025, with their annual share fluctuating between 38% and 53%.

To isolate the structural dynamics at play, bonds issued by banks (public or private) are excluded from this analysis. These instruments, including Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 capital bonds, serve specific regulatory functions and are not directly comparable to conventional corporate debt.

Even after excluding banks, the dominance of CPSUs remains pronounced. Their issuance consistently exceeds one-quarter of the total market, and in some years approaches one-third – a trend that is both persistent and policy-relevant.

Anatomy of issuance: Long tenors, low yields

A more granular look at the top issuers over the past five years reveals stark contrasts between CPSUs and AAA-rated private sector borrowers – not only in terms of identity, but also in bond structure and pricing.

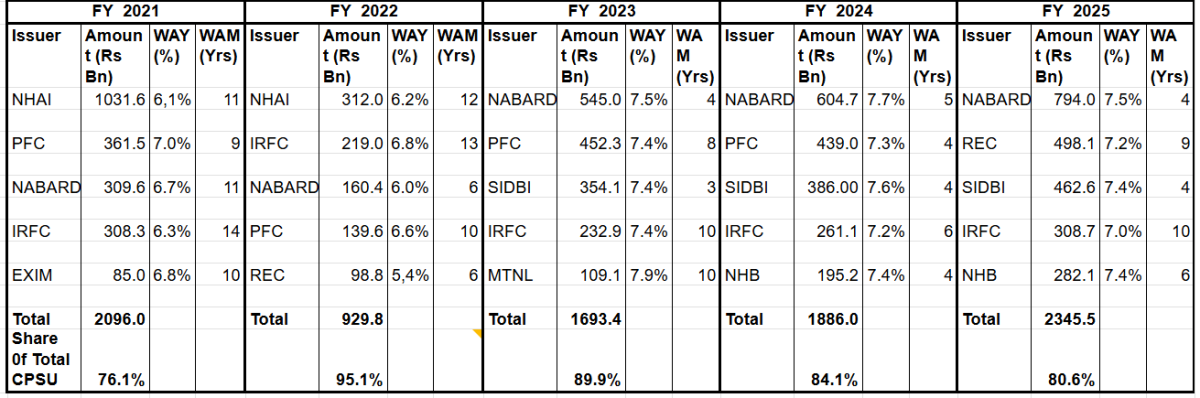

Tables 1a and 1b, compiled from data provided by the National Securities Depository Limited (NSDL) and Prime Database, show that CPSUs typically issue longer-dated paper, with weighted average maturities (WAM) exceeding eight years. By contrast, the WAM for AAA-rated private issuers is closer to five years. The only notable exception was FY2021, when pandemic-era monetary easing prompted private firms to lock in long-term funding at historically low rates.

Table 1a. Top five CPSU bond issuers, FY21-FY25

Table 1b. Top five private sector AAA bond issuers, FY21-FY25

Source: Author’s computations using NSDL data.

This divergence is significant. Long-dated paper carries inherently greater duration risk, yet CPSUs routinely raise such funds at lower yields than their private sector peers. The implication is clear: investors are pricing in a credit enhancement not reflected in the standalone fundamentals of the issuer.

Deconstructing the CPSU pricing advantage

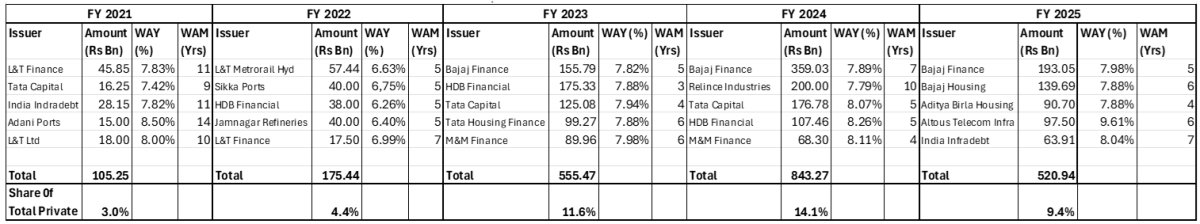

To understand the pricing asymmetry, one must examine the credit risk premium – defined as the yield spread between a corporate bond and a government security of comparable maturity. As Government of India bonds are effectively considered risk-free, the spread captures the market’s perception of credit risk.

Figure 2. Yield of Government of India securities

Source: Bloomberg.

Data from Bloomberg and Prime Database show that CPSUs consistently enjoy narrower credit spreads relative to private sector firms, despite carrying the same nominal AAA rating. Across maturities, the yield advantage ranges from 50 basis points to as much as 135 basis points.2 In bond market terms, such differentials are far from trivial. For large issuances, the savings can amount to hundreds of crores in annual interest expense.

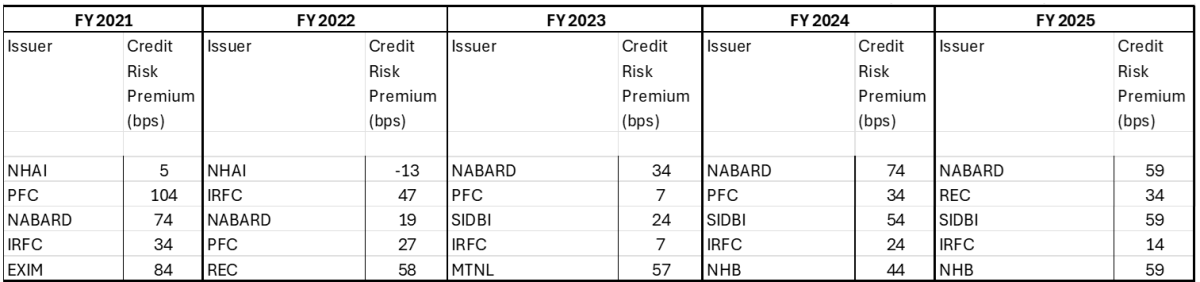

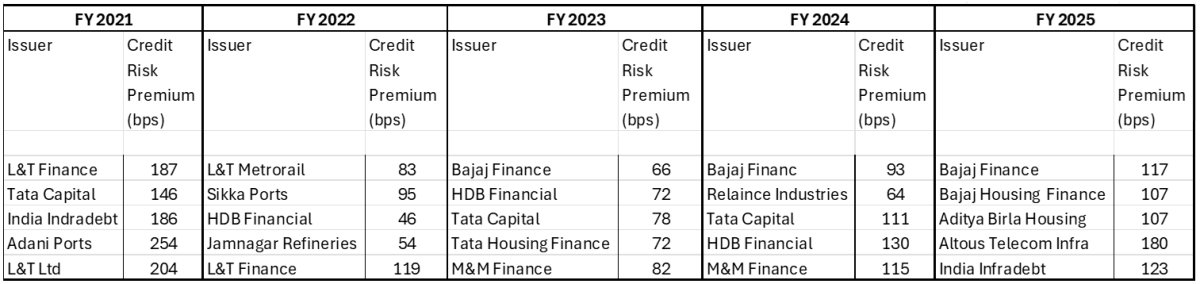

Table 2a. Credit risk premium of top five CPSU bond issuers over matched maturity risk-free rate (Government of India security yield)

Table 2b. Credit risk premium of top five private sector AAA bond issuers over matched maturity risk-free rate (Government of India security yield)

Source: Author’s computations using data from NSDL, Prime Database, Bloomberg.

This advantage becomes even more striking when placed against the rationale offered by credit rating agencies. Reports from Crisil on entities such as the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), the Indian Railway Finance Corporation (IRFC), and the Power Finance Corporation (PFC) repeatedly cite government ownership and strategic importance as the basis for the AAA rating.

Consider the following extract from Crisil’s 2024 rating report on NABARD:

“The ratings continue to reflect the expectation of continued strong support from the Government of India (GoI), given NABARD’s key public policy role in India’s agriculture sector. The ratings also factor in NABARD’s strong capitalisation, robust asset protection mechanisms, and adequate resource profile.”

Similar language recurs across reports and years. The credit assessment of IRFC hinges on its role as the financing arm of Indian Railways, while PFC’s rating reflects its function in funding India’s power sector – despite acknowledged weaknesses in asset quality and revenue concentration.

This pattern suggests that the AAA rating is less an endorsement of financial strength than a proxy for government linkage. Indeed, were these firms to be rated on a standalone basis, absent the sovereign halo, many would struggle to secure even investment-grade status.

The cost of implicit subsidy

The implications are not merely academic. In FY2025 alone, CPSUs – including State-owned banks – issued Rs. 5.7 trillion worth of bonds. Even assuming a conservative 50 basis point yield advantage, this implies an annual interest saving of Rs. 28 billion. Over an average maturity of eight years, the effective interest subsidy for one year’s issuance amounts to Rs. 228 billion.

This subsidy, though not budgeted or recognised, constitutes a de facto contingent liability for the government. None of these instruments carry explicit sovereign guarantees. Yet, the market behaves as though a bailout is assured – effectively transferring credit risk from investors to taxpayers.

Such implicit guarantees are not costless. They create moral hazard (tendency to take risks when protected from consequences), distort credit allocation, and inhibit the development of a competitive and diversified bond market. In particular, they disadvantage private sector borrowers, who must compete for capital against State entities enjoying preferential pricing.

Crowding out and market inefficiency

The sheer scale of CPSU issuance and their pricing edge have cascading effects. Institutional investors – particularly pension funds and insurers – are incentivised to allocate a disproportionate share of their portfolios to these bonds, given the combination of long tenor, high rating, and yield pickup over government securities.

This crowds out private sector issuers, especially those without large balance sheets or State linkages. It also narrows the investor base for mid-tier or unrated corporates, who are then forced to rely on bank lending or non-bank finance companies, often at higher cost and shorter tenors.

Over time, this bifurcation undermines market efficiency. The bond market, rather than serving as a neutral platform for capital allocation, becomes skewed in favour of entities that carry implicit State guarantees. The net result is a less dynamic corporate debt ecosystem and reduced capital access for the very firms that may drive innovation and employment.

Charting a path to reform

To address these distortions, several policy interventions merit consideration. First, rating agencies should be required to disclose both a standalone and a support-adjusted rating for State-owned enterprises. This dual-rating approach – common in developed markets – would offer investors greater transparency and improve pricing accuracy.

Second, the government must clarify the nature of its commitment to CPSUs. If support is to be extended in distress scenarios, then an explicit guarantee mechanism should be established. Conversely, if such support is not assured, this should be publicly stated to help recalibrate market expectations.

Third, regulators could introduce credit enhancement mechanisms for private sector issuers – particularly in infrastructure and green finance. Instruments such as partial guarantees or first-loss capital buffers could help level the playing field, allowing more diverse borrowers to access long-term debt on competitive terms.

Finally, large institutional investors – especially the Employees' Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO), which manages substantial public retirement savings – should be encouraged to diversify beyond CPSU paper. Regulatory nudges or portfolio benchmarks could be deployed to promote broader risk dispersion.

Toward a more balanced bond market

As India aims to become a developed economy by 2047, the need for a deep, efficient, and balanced debt market has never been more urgent. Mobilising capital for climate action, infrastructure, and innovation will require not just volume but quality – capital that flows to its most productive use, not merely to its safest haven.

The present structure of India’s bond market, with its implicit subsidies and concentration risks, poses a serious impediment to this ambition. Addressing these issues will require regulatory courage, policy clarity, and a willingness to confront long-standing assumptions about State support.

The bond market is, by design, a reflection of trust and discipline. To maintain both, India must ensure that risk is priced accurately, that support is transparent, and that the playing field is level – for public and private issuers alike.

Dr Harsh Vardhan is a management consultant and researcher based in Mumbai.

The author thanks Monalisa Paoli for excellent data and research support. The views expressed in this post are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the I4I Editorial Board.

Notes:

- Rating firms use different designations to identify a bond's default probability - "AAA" and "AA" (high credit quality or low default probability) and "A" and "BBB" (medium credit quality) are considered investment grade, while credit ratings below these are considered low credit quality (or high default probability).

- One basis point is 1/100th of a percent and is commonly used to measure movements in interest rates.

This article was first published on Ideas For India.

This article went live on June sixteenth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-nine minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.