Unpaid Labour on the Rise, Muslims Not Looking For Work: What the PLFS Data Reveals

New Delhi: A significant number of individuals in India are engaging in self-employment or unpaid labour, shows the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data, for July 2022 to June 2023.

Moreover, the data highlights that, among the major religious groups, only Muslims have experienced a decline in their labour force participation rate (LFPR) and worker population ratio (WPR).

The PLFS was launched by the National Sample Survey Office in April 2017. It estimates the key employment and unemployment indicators such as Worker Population Ratio, Labour Force Participation Rate, and Unemployment Rate. It further measures the employment status among social and religious groups.

Among the major religious groups, it names "Hinduism, Islam, Christianity and Sikhism".

On a positive note, the latest data indicates that India's unemployment rate for individuals aged 15 and above has reached a six-year low, standing at 3.2%.

The data shows a decrease in the unemployment rate in rural areas from 5.3% in 2017-18 to 2.4% in 2022-23, and in urban areas from 7.7% to 5.4%.

While these statistics may seem encouraging at first glance, it's essential to examine the finer details to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the situation.

The increasing share in self-employment

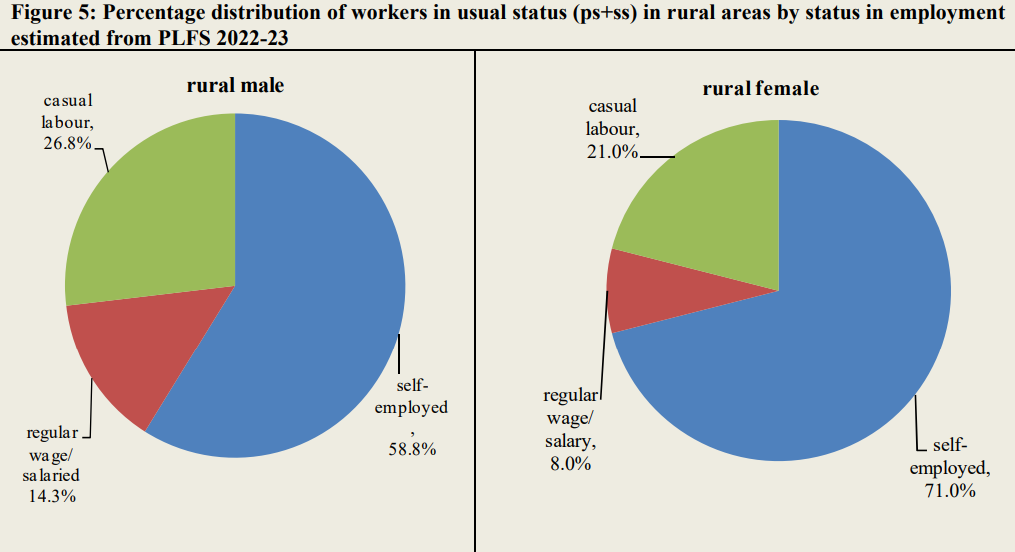

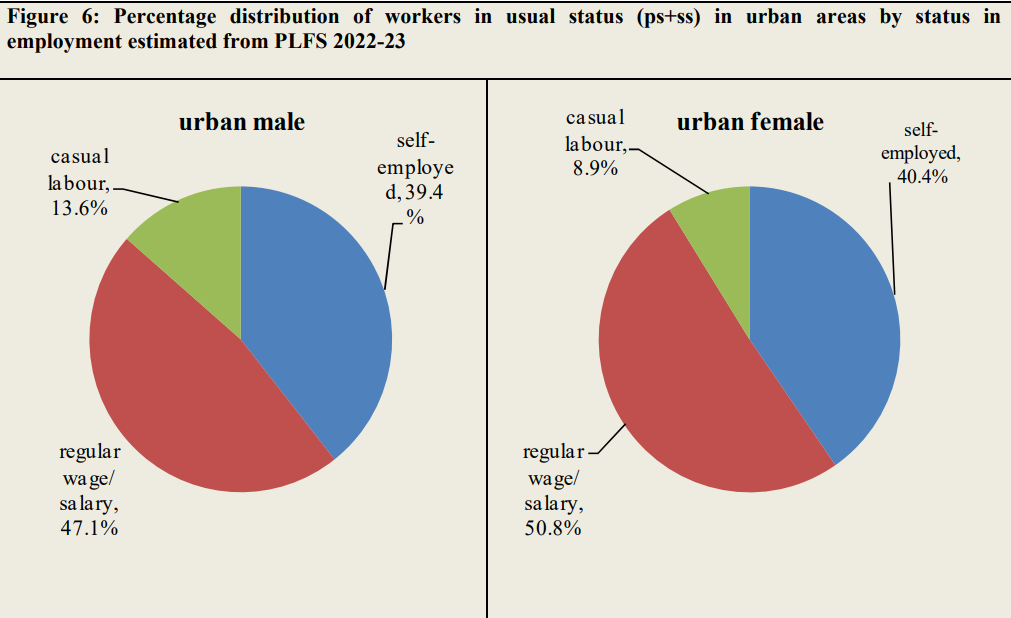

According to the PLFS data, a larger number of individuals are self-employed than those in casual labour and the regular salaried class.

In urban areas, a relatively higher number of people have salaried jobs as opposed to self-employment.

The PLFS divides employment status for workers into three broad categories: (i) self-employed, (ii) regular wage or salaried employees, and (iii) casual labour.

The overall rate of self-employed people increased to 57.3% in 2022-23 from 55.8% in 2021-22 and 55.6% in 2020-21. It was around 52% in 2017-18 and 2018-19.

Note that 2022-23 refers to the period from July 2022 to June 2023 and likewise for 2021-22, 2020-21, 2019-20, 2018-19 and 2017-18.

Within the self-employed category, two sub-categories have been established, which include: (i) own account workers and employers, and (ii) unpaid helpers in household enterprises.

"So [the] employer [category] is barely under 2% of the number of people in the economy. In other words, the own account workers' category is highly driven by people such as the cultivators, weavers, potters, who work on their own, in rural areas. And in urban areas, they are the redi walas, thele walas, kabaadi, barbers, tailors, vendors, those who're working on the street. The share of self-employed [people] in the total workforce is increasing, and within that most of the increase can be seen among unpaid family labour and own account workers," said Santosh Mehrotra, professor of economics, Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Unpaid labour – which is categorised as 'helper in household enterprise' within self-employment – has increased to 18.3% in 2022-23 from 17.5% in 2021-22 and 17.3% in 2020-21.

"A regular worker gets a salary, an unpaid family labour within the self-employed gets nothing; an own account worker, [as earlier mentioned], is someone who in rural areas is a cultivator and will earn something when their crop is finished and [when] they sell it. So, what's happening is that regular people [who have] lost work have gone to do something on their own," he said.

He further explained that people are choosing to be self-employed, because of a lack of good work and wages. For example, an educated person would not want to do casual labour jobs.

He elaborated saying: "If the casual labour has reverse migrated back to his village, then he could be now doing MGNREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme) work sometimes, or has gone back to work on his family farm."

He added that there's another situation where women who had dropped out of the workforce return only to help their husbands. And that has happened consistently, on a massive scale, and distress has increased in the economy over the last five years.

Also read: The Stories of Women Who Migrate Alongside Their Husbands to Work as ‘Helpers'

"If you wish to call this kind of distress-driven employment 'employment', [may] god help you. This is the main reason why unemployment rate is supposedly decreasing," he said.

The Indian Express, in its editorial, published in September 2023, underscored the need to appreciate the quality of the jobs being created.

"For instance, providing “casual labour” at a MGNREGA worksite or a construction worksite or working part-time in one’s family enterprise without any pay (“self-employment”) are very poor substitutes for holding a job that provides a regular wage," it said.

Mehrotra further asked why the CMIE is showing the opposite. This is because" it doesn't include unpaid family labour as employment," he said.

According to CMIE, the Indian youth is increasingly getting driven out of the job market, and that India’s workforce is ageing, which should be a matter of concern for policymakers. "CMIE also shows that unemployment rate rose, and labour force and employment rates (as a share of the total in working age) both fell," he added.

The employment numbers in other sectors

Apart from that, the percentage of people in better paying jobs such as manufacturing, construction, etc. have remained stagnant but, as mentioned earlier, the number of self-employed people has relatively increased.

The percentage of people working in the manufacturing sector was 11.4% in 2022-23. It was slightly higher at 11.6% in 2021-22, and in the preceding year, it stood at 10.9%.

The percentage of people working in the construction sector was 13% in 2022-23. It was 12.4% and 12.1% in 2021-22 and 2020-21, respectively.

Interestingly, people working in the trade, hotel and restaurant sector remained stagnant at around 12% from 2020 to 2023.

A similar trend can be observed in the percentage of people working in the transport, storage, and communications sectors, where only around 5% were employed.

Separately, the percentage of regular wage/salaried employees, who are not eligible for any specified social security benefits, in rural India, has risen to around 60% in 2022-23 from 58.2% and 59.1% in 2021-22 and 2020-21, respectively.

In urban areas, the percentage has declined from 50.1% in 2020-21 to 49.4% in 2022-23.

However, overall, the percentage has remained stagnant at around 54% for all these years.

Also read: Three Claims of Government Economists About Jobs Put to the Test

Data shows Muslims are not looking for work

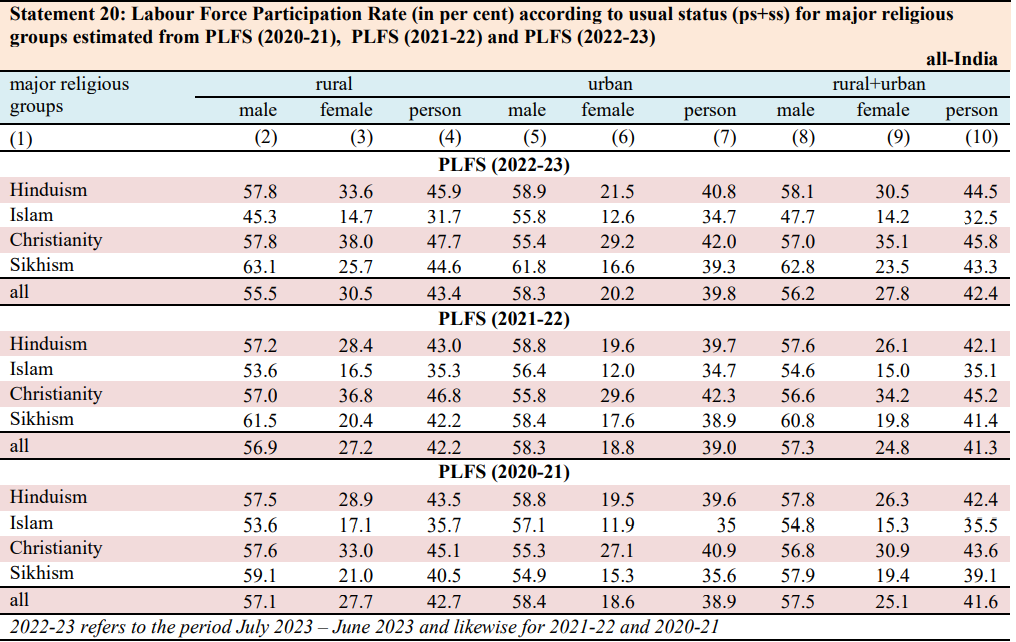

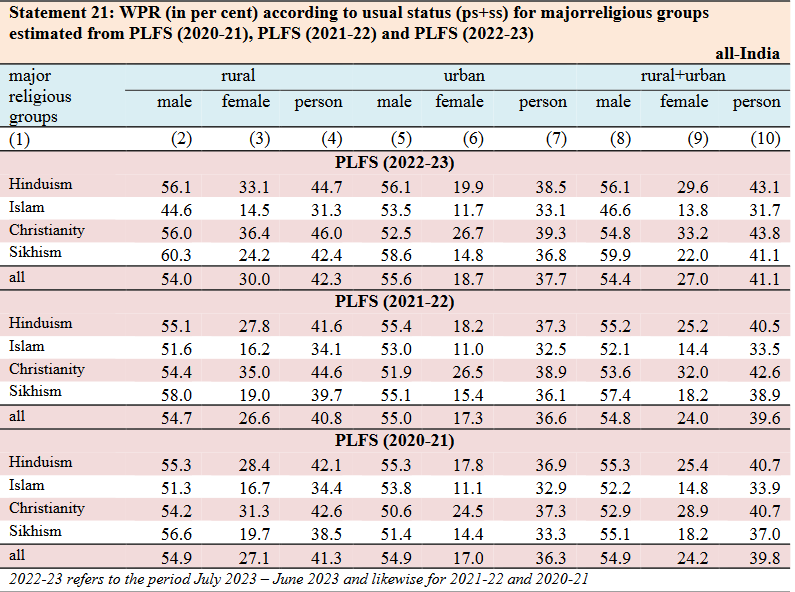

Notably, the PLFS survey shows that among major religious groups, the labour force participation rate (LFPR) and worker population ratio (WPR) of only Muslims have declined.

The labour force participation rate is the share of population which is looking for work, and the worker population ratio is the share of the working age population that has work.

The LFPR for ages 15 years and above increased to 57.9% in 2022-23 from 55.2% in 2021-22 and 54.9% in 2020-21. It was 49.8% in 2017-18 and 50.2% in 2018-19.

The WPR for persons of ages 15 years and above increased to 56% in 2022-23 from 52.9% in 2021-22 and 52.6% in 2020-21.

However, the LFPR and WPR for only the Muslim community has fallen.

For Muslims, the LFPR stood at around 35.5% in 2020-21 and 35.1% in 2021-22. It declined to 32.5% in 2022-23.

"In other words, from lower than national LFPR and WPR, Muslims have seen further falls," Mehrotra said, explaining this data point.

Similarly, the WPR for Muslims stood at 33.9% in 2020-21 and 33.5% in 2021-22. It declined to 32.5%.

"So, the LFPR sees a 2.6 percentage points decline [as compared to 1.8 percentage points decline in the WPR.] This shows Muslims are not looking for work," Mehrotra said.

According to Mehrotra, this is clear evidence that the Muslims have taken the brunt of the fall in jobs even though the labour market should have revived after COVID-19. "This is [the data] for the first full post-COVID-19 year," he added.

He further explained that "Muslims have a higher share in the urban population than their share in the rural population. [This is] because most Muslims live in urban areas. So, when the labour market revived in the first post-COVID year, unfortunately, there's has been a sharp 2 percentage point decline in the WPR of Muslims."

"[Note that] WPR tracks the LFPR...As the labour market revived, this is clear evidence that the Muslims have taken the brunt," he said.

This article went live on October sixteenth, two thousand twenty three, at seven minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.