Scene 1: Struggles of a marginalised student

On January 6 this year, Paresh Hansda, an assistant teacher at Susunia High School, visited Dulali Mandi’s home in Paharbediya village of Chhatna Block, Bankura district. This village lies adjacent to the picturesque Susunia Hill, a well-known tourist destination in West Bengal. Dulali Mandi’s son, Bapon, was promoted to Class 9, but he has not yet re-enrolled, despite the readmission process having started on January 2. Enrollment in Class 9 is critical for students, as it is a prerequisite for appearing in the Madhyamik (Class 10 or board) examination.

Hansda urges Dulali to ensure her son’s immediate readmission. However, she responds, “Bapon is not at home. He left for Bangalore six months ago to work as a migrant labourer. He sends me Rs 15,000 per month to support our family. Can you assure me that studying here will secure him a job? How will we survive if he returns to school? Will you provide Rs 15,000 per month? What will education change for him?”

Faced with these questions, the teacher has no answer. Speaking to The Wire, Hansda laments, “A large number of students have dropped out to seek work elsewhere. The situation is worsening rapidly. We are trying to bring students back to school, but socio-economic realities act as major barriers. The future of education is uncertain.”

Sukuntala Shabar, her sister Mamoni and Jadu had to similary leave school in Muradi village under Binpur 2 Block, Jhargram.

Scene 2: A lost opportunity and a mother’s determination

In Kodopura village, Binpur II Block, Jangalmahal, Jhargram District, a severely malnourished 21-year-old woman, Mangala Baske, was carrying her three-year-old daughter home from the local Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) centre. In her hand was a plate of khichuri (one-pot meal) and a boiled egg – nutritional supplements provided by the ICDS.

Mangala shares her story: “During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Kodopura High School shut down and has not reopened since. At that time, I was studying in Class 9 and living in the school hostel. When the school closed, my parents arranged my marriage. I wanted to continue studying, but it was not possible. Even now, I dream of being back in my classroom.”

She adds, “Most of the girls in my school were forced into early marriages, while the boys migrated to other states for work. My husband is a migrant worker in Mumbai, employed as a mason. Despite financial struggles, I am determined to educate my daughter so that she does not have to drop out like I did.”

However, Mangala also voices concerns about the education system’s future. “There is no school near Kodopura. The nearest ones are in Balichuya and Adalchuya, 4 kilometers away through a dense forest. I also hear that there were allegations of corruption in teacher recruitment. If those teachers are dismissed, the situation will only worsen.”

Scene 3: A dying school and desperate teachers

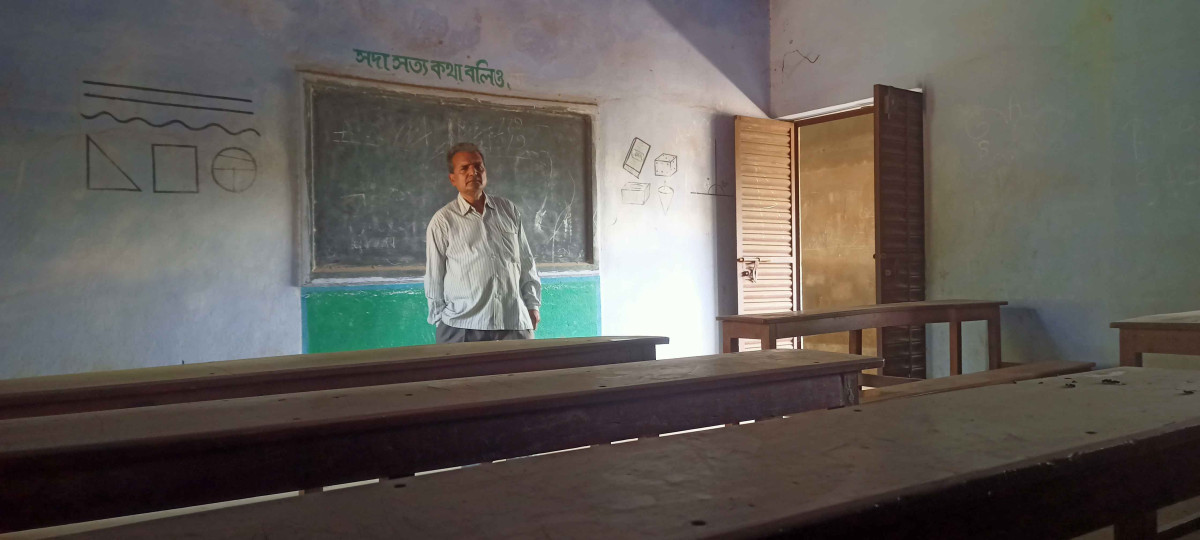

Three days ago, Ramsankar Patra, a teacher at Radhamadhab Madhyamik Shikshakendra (MSK) in Kumidda village, Bankura I Block, was seen anxiously pacing in the scorching 40-degree Celsius heat. By 11:30 AM, not a single student had arrived.

This school once had six teachers and over 300 students enrolled from Classes 5 to 8. However, after the Trinamool Congress (TMC) came to power, no new teachers were appointed. As older teachers retired, the school fell into crisis. Today, only two teachers remain to manage four classes, and fewer than ten students attend regularly. On January 7, the district administration issued an order to shut down seven MSKs in Bankura District, including this one.

A teacher in a classroom at Radhamadhab Madhyamik Shikshakendra (MSK) in Kumidda village, Bankura, which has ordered by the administration to be closed.

“Poor and marginalised families live here. The nearest high school is 4 kilometres away. How can teenage boys and girls travel such a distance? The Left government established this MSK to address this issue. If the (TMC) government had appointed more teachers, students would have continued their education,” laments Ramsankar Patra and Mrityunjoy Banerjee, the head teacher. Their eyes well up as they plead, “Save the school, at any cost.”

Residents Bulu Dasmohoto and Mousumi Poramanik echo their concerns. “There have been no adequate teachers for years. How can we send our children to a school that lacks educators? Many have already dropped out.”

***

1950s-1970s: State of education in West Bengal

At the time of India’s independence, in 1947, West Bengal had 8,431 primary schools and approximately 2,000 high schools. Following the partition, several local zamindars and educators took the initiative to establish more schools across the state. However, most of these schools operated in mud houses and lacked proper infrastructure.

“Due to extreme poverty, many families did not send their children to school. High school education required a monthly tuition fee, which made it unaffordable for many. Teachers were paid through these fees and often struggled to sustain themselves,” says Akalanka Maity, an octogenarian retired headmaster of Garhjoypur High School in Purulia and Tiluri High School in Saltora, Bankura.

Several primary teachers from the 1960s and 70s, including Biswabhar Das, a retired headmaster of BDR Primary School, described the hardships faced by educators at the time. Salaries were meagre and were disbursed through post offices every three to four months, making financial stability a significant challenge for teachers.

Transformations in school education after 1977

The landscape of school education in West Bengal underwent significant changes after 1977 when the Left Front came to power. One of the first major reforms was the removal of tuition fees in high schools, making secondary education more accessible. Teachers’ salaries were increased and started being disbursed regularly, marking an end to the financial uncertainty that many educators had faced.

Jyoti Basu, the then chief minister assured teachers that the government would take responsibility for their salaries and dignity, a promise that was largely upheld, according to Jnanshankar Mitra, an octogenarian teacher and former Sabhadhipati (chief of district Elected development authority) of the Bankura Zilla Parishad. The government also initiated the construction of concrete school buildings with financial grants, improving the overall infrastructure of schools.

Additionally, the implementation of land reform policies improved the economic conditions of poor and marginalised communities, leading to higher school enrollments.

“After the land reforms, more families found stable work in their local areas, and children from these families started attending school,” says Amal Haldar, secretary of the Sarbharat Krishak Sabha, and Amiya Patra, a state leader of the Khetmajur Union of West Bengal.

Girl students appearing for higher secondary exam at Bankura Kenduadihi Girls High School.

While these reforms expanded access to education, challenges remained. Until 1996, high school teachers were recruited by school management committees, which led to inconsistencies in hiring. In 1996, the Left government introduced the School Service Commission (SSC) to standardise recruitment, which allowed many talented candidates from lower-income backgrounds to secure teaching jobs.

“Various initiatives, including literacy programs, encouraged students from families that had never considered education before to attend school,” says Sudipta Gupta, an assistant teacher at Ichhlabaid High School in PurbaBardhaman and president of the All Bengal Teachers’ Association (ABTA). He also pointed out that in the 2011 Census, while India’s national literacy rate stood at 73%, West Bengal recorded a literacy rate of 77%, indicating the impact of these policies.

The declining student enrollment in the last decade

Despite past progress, recent trends indicate a worrying decline in student enrollment for higher secondary education in West Bengal. Compared to the previous year, the number of students appearing for the higher secondary examination has dropped by 2,46,324. According to the West Bengal Council of Higher Secondary Education (WBCHSE), this year, approximately 5,09,443 students are appearing for the higher secondary exams, with 55% being female students. In contrast, last year, 7,55,324 students had appeared for the same examination.

WBCHSE has attributed this decline to a shift in the admission age policy. In 2013, the state government mandated that children must be at least six years old to enroll in Class 1. As a result, students currently taking their higher secondary exams had entered the education system a year later than previous batches, leading to a temporary drop in numbers.

However, many educators disagree with this explanation. They argue that student dropout rates are the primary reason for the declining numbers.

A mid-day meal centre at Shibarampur primary school in Bankur I Block.

“In 2023, 6,98,627 students appeared for the secondary examination, and 5,65,120 students passed. But this year, the number of higher secondary candidates is only 5,09,443. Where did the 56,000 missing students go?” questions Sukumar Paine, general secretary of the All Bengal Teachers’ Association (ABTA).

He also challenged the claim that the number of female students has increased.

“In 2023, 3,20,000 female students passed the secondary examination. This year, only 2,77,000 of them have enrolled for the higher secondary exam. What happened to the remaining students? The Higher Secondary Council must provide a clear explanation,” he adds.

The worsening state of schools

The TMC-led Bengal state government launched the Bangla Shiksha portal, following the Central Education Act of 2020. According to the act, once a student is admitted to Class 1, they will be promoted up to Class 8, regardless of attendance. Prasanto Choudhury, an assistant teacher at Chhatna Chandidas Bidyamandir in Bankura, Chinmoy Nandi, an assistant teacher at Purulia Joypur High School and Biman Parta, headmaster of Natungram Primary School in Bankura, stated that no significant initiatives have been taken to ensure students attend school. Some teachers attempt to bring students to class through personal efforts.

Ramsankar Patra is the only teacher at Radhamadhab Madhyamik Shiksha Kendra, Kumidda village , Bankura.

Previously, the village education committee (VEC) actively monitored the education system, but it has now been abolished. High school managing committees have not been elected for 14 years and are instead government-nominated, allegedly controlled by ruling party activists.

Teacher-student ratio: Norms vs. reality

According to the Right to Education Act, 2009, the ideal student-teacher ratio should be 30:1. In 2008, this ratio was 35:1 in Bengal. However, due to a severe shortage of teachers, the current ratio has risen to 70:1, said Sudipta Gupta.

In 2018, the state government upgraded many secondary schools to higher secondary levels but failed to provide the necessary teachers. As a result, students enrolling in higher secondary education, especially in the science stream, have been severely affected.

Several higher secondary schools, including Bishnupur Sibdas Girls’ School, Saltora Tiluri High School and Patrasayer Bankisole High School, have shut down their science departments. In the few schools where the science stream still exists, there are often only one or two teachers, with no laboratory assistants.

Students from various parts of Bengal’s Jangalmahal region – including Bankura, Purulia and Jhargram – expressed their distress over the lack of science teachers in their schools. Many students have had to discontinue their education due to the lack of academic support.

School closures and student dropout rates

Sukla Majumdar, a teacher at Belpahari S.C. High School, and Krishna Prasad Mandi of Muradi S.C. High School in Jhargram stated that 32 high schools in the district have been shut down due to a lack of teachers. As a result, numerous students have lost interest in education. Many have migrated to other states as labourers due to the absence of local job opportunities, while a significant number of girls have been forced into early marriage.

Gurupada Nandi, a teacher at Joypur High School in Jhargram, claimed that the government uses the Bangla Shiksha portal to falsely show that there are no student dropouts. In reality, many schools operate with only a handful of students and teachers. For instance, Teliyabhasa Junior High School in the Ayodhya Hills, a tribal-dominated area, has been functioning with just one teacher for the past 14 years.

Meanwhile, Punisol Board High School, located in a Muslim-majority area, has an enrollment of over 3,000 students but only 26 teachers. As a result, students get to attend classes only on certain days.

Twelve-year-old Sima Bauri had to leave school. Now she works at a brick kiln at Poyabagan, Bankura.

“If Class 7 and 8 students attend school for two days a week, they do not get a chance to attend on the remaining days, as other classes take their place,” says Sakil Aktar Khan, a Class 11 student. Anarul Islam Khan, a Class 9 student from the school, agreed.

At present, 3,98,150 teaching and non-teaching positions remain vacant in West Bengal, from the primary to higher secondary levels.

Piyus Bera, the district inspector of schools (secondary), Bankura district, admitted that the number of teachers is far below the required level but said that the government was trying its best to manage the situation. However, he noted that the final decision rests with the state authorities.

Corruption in teacher appointments

In 2018, the West Bengal School Service Commission (SSC) appointed 26,000 teachers and non-teaching staff at the secondary and higher secondary levels. In 2017, over 20,000 teachers were appointed in primary education. However, after the recruitment process, numerous candidates alleged large-scale corruption, claiming that deserving and qualified candidates were denied jobs.

The Kolkata High Court ordered the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to probe the allegations. The CBI uncovered massive corruption, the most shocking revelation being when Rs 20 crore in cash was recovered from the house of former state education minister Partha Chatterjee, leading to his arrest.

Several high-ranking officials were also arrested, including former SSC chairman Subiresh Bhattacharya, former chairman of the State Secondary Education Board Kalyanmoy Ganguly, SSC advisor Santi Prasad Sinha and former chairman of the State Primary Education Board Manik Bhattacharya. Of them, only Manik Bhattacharya has been granted bail, while the rest remain in judicial custody.

Many believe this is the largest corruption scandal in West Bengal since independence. Parents and students alike are losing confidence in the government’s education system.

Madrasa education in Bengal

There are 10,000 vacant teaching and non-teaching positions in 614 madrasas across Bengal.

“There have been no new appointments for many years. Several schools are in a dire state due to a lack of teachers and staff. We have repeatedly informed the Minority Department, but the government has taken no positive steps,” says Azijur Rahaman, headmaster of Natungram High Madrasa.

Students in a classroom at Nutungram High Madrasa, under Anchuri Gram Panchayat, Bankura.

Ten years ago, the chief minister announced that the government would approve 10,000 unaided madrasas, but only 235 have been approved.

“There are 2,350 teachers in the newly approved madrasas. Each teacher receives only 6,000 rupees per month as salary. We have had to face police brutality multiple times in Kolkata just to get approval for this nominal allowance,” he adds.

Student hostels shut

Across the state but especially in Jangalmahal, a large number of students from poor, marginalised families in Bankura, Purulia, Jhargram, and Paschim Medinipur districts used to stay in hostels while pursuing their education. Earlier, the government used to pay hostel expenses directly to school accounts, but a few years ago, the system changed, and the money was sent directly to students’ accounts.

Closed student hostel of Sususinia high school under Chhatna Block, Bankura.

“Due to multiple complications, most student hostels have now shut down,” says Uttam Khan, Headmaster of Haludkanali High School, Ranibandh, Bankura, along with Sanjit Pator, a teacher at Sukhjora High School in Jhargram. They stated that many boys and girls have dropped out due to hostel closures.

Paresh Handa, another teacher, noted that out of 209 student hostels in Bankura district, 173 have shut down.

Decline in girl students, rise in RSS-affiliated schools

Notably, Kanyashree Prakalpa is one of the most recognised projects in Bengal’s education sector and has received international accolades. Under this scheme, girl students from class eight up to the age of 18 receive Rs 1,000 per year. If they remain unmarried until 18, they receive a one-time grant of Rs 25,000. However, this year, the state’s budget allocation for the Kanyashree project has been reduced.

Last year, the allocation stood at Rs 1,384.56 crore but it has now been cut to Rs 816.31 crore.

ABTA’s Sukumar Paine said that the state budget reflects a declining number of girl students in the education system. He mentioned that rural and urban Bengal lacks employment opportunities and MGNREGA work has been halted for four years. The Karmashree project, which was supposed to be monitored by the state government, has not received any allocation in this year’s budget. Due to their parents’ lack of work, many students are unable to afford the cost of education.

The current dropout rate in West Bengal is 18.75%, and the state has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the country. In this situation, private schools are expanding, especially those affiliated with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), spreading rapidly across Jangalmahal. The TMC government has been approving these RSS-affiliated schools.

Six years ago, Dipika and Joyanti Shabar left school in Barikul village. They got married.

Regarding this issue, Tapas Banerjee, a state leader of the Trinamool Shiksha Cell and a teacher at Deuli High School in Hirbandh Block, Bankura, along with a member of the West Bengal Tribal Cultural Development Board from Jhilimili, Bankura, argued that women are receiving financial aid through social welfare schemes like Lakshmir Bhandar, and students are getting support from schemes like Shikshashree and Kanyashree.

However, they acknowledged that hostel closures and teacher shortages have impacted the education system. They assured that they have raised these concerns with the government.

All photos are by Madhu Sudan Chatterjee.