Eroding Scientific Rationality Is Undermining Knowledge Production in India

“Science is not just a body of knowledge; it’s a way of skeptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility”.

- Carl Sagan

A few weeks ago, the Union government wrote to over 350 heads of scientific institutes to identify the key hurdles in scaling Research and Development (R&D) in India. The initiative led by NITI Aayog aimed to address funding challenges, administrative hurdles, and regulatory issues. The move was part of the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), set up in 2023 to draft an 'ease of doing research' mechanism to help researchers focus on R&D rather than spending hours on operational hurdles.

While ANRF appeared to be a sound initiative, its success depends on the research spaces in the country's higher academic institutions. Increasing administrative interferences, academic appointments largely based on political or ideological loyalty rather than merit, incremental political pressure stifling critical voices, and defunding instances have severely affected these institutions' ability to carry out robust intellectual engagement and promote scientific temper, critical thinking and rationality - the ingredients that lie at the heart of the enterprise of knowledge production. By legitimising dubious claims and quoting the scriptures, the proponents of Hindutva generate a narrative of modern science as an echo of Vedantic philosophy.

A worldwide change

Centralisation of academic curriculum through diktats from the University Grants Commission and the National Education Policy deprives the universities of their autonomy in exercising their discretion in organising academic programmes. In contemporary times, the erosion of academic freedom is not confined to India. In recent months, the Trump administration has actively sought to restrict academic freedom within leading research institutions in the United States. Assault on science in America is largely still at the level of institutions and funding, motivated by anti-woke, anti-climate and anti-vaccine rhetoric. Similarly, countries like Hungary and Turkey have experienced widespread crackdowns on academia.

In India, the assault is ideological and motivated by religious zealotry. Since the current political regime assumed power, India's ranking on the Academic Freedom Index, developed by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, has sharply declined. In its 2024 update, the report categorises India among countries where academic freedom is deemed 'completely restricted'. The report suggested that 'it is primarily anti-pluralist parties in the government that contribute to the decline in academic freedom'.

While the incumbent regime primarily targets social sciences and humanities to reduce them to inconsequential subjects, research in the sciences and medicine could not escape State scrutiny. They have been particularly effective in peddling pseudoscience and bringing its status on par with evidence-based modern science. They have also been successful in branding Hindu scriptural epistemology as ‘Indian Knowledge System’, and making it a part of the educational syllabus, legitimising Hindu metaphysics and mythology as science and history. At the same time, criticism from educators regarding the National Council of Educational Research and Training’s (NCERT) decision to remove Charles Darwin’s theory of biological evolution from the 10th-grade science textbook was dismissed, with the move being justified as part of a 'curriculum rationalisation exercise.'

Also read: Political Intolerance and Declining Academic Freedom in India

The push for inclusion of the ‘Indian Knowledge System’ in the National Education Policy meant that pseudoscientific topics like astrology can now be included in school and college syllabi. Meera Nanda, in one of the chapters of her recent book, A Field Guide to Post-Truth India, discusses how the Ministry of Ayush used the COVID-19 pandemic to issue an advisory recommending ayurvedic, homoeopathic and Unani decoctions for preventing and treating the disease and how the Union government moved to foster Ayurveda as a cure for COVID-19 that facilitated brand ambassadors like Ramdev and his multi-crore company, Patanjali to enter the fray, hoodwinking the people on the questionable efficacy of his Ayurvedic antiviral pill. As Nanda asks, why did AYUSH ignore the first principle of medicine – ‘to do no harm’, while sponsoring such remedies that are not backed by robust science?

Why would the government advance bovine dung and urine as a panacea for ailments, including cancer? Why would ministries broadcast the misguided views of self-styled experts as scientific fact and confuse the public? The Ministry of AYUSH has been vigorously campaigning for research on cow products, which it believes have medicinal properties. Aside from some antiquated beliefs, these claims had nothing else by way of support, especially no peer-reviewed research or clinical tests. Researchers from major institutes recently gathered at a temple in Madhya Pradesh with their equipment to determine the efficacy of fire rituals in bringing rain. This tells a lot about the abandonment of scientific rationality in contemporary India to suit the whims of the establishment. Such instances reflect the diminishing quality of scientific research in India and draw our attention to how the state instrumentalises knowledge to serve political ends.

History and institutions

As with many majoritarian regimes, rewriting history becomes central to constructing a homogeneous vision of the past that serves the interests of the ruling dispensation. This singular historical narrative typically emphasises the grandeur of an ancient civilisation and seeks to forge a unified present rooted in the ideology of Hindutva. Beyond whitewashing complex historical realities, these aspirations directly challenge the normative ethos of democracy that encourages the free flow of information, unfettered inquiry, and meaningful public engagement as crucial ingredients of knowledge production. At the heart of knowledge creation lies the intrinsic impermanence of established knowledge. However, intellectual incapacity to provide robust criticism is becoming integral to the research institutions today.

Institutional autonomy is also in a crisis mode, hindering rigorous intellectual enquiry based on logic and empirical evidence. What has happened to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) will serve as an exemplifier here. Established in colonial times as an epistemic institution dedicated to generating knowledge through scientific methodologies, became a key instrument for the ruling party to advance its historical agenda. In post-colonial India, the ASI retained its hierarchical and bureaucratic structure. Ashish Avikunthak, in a robust ethnographic work, noted that in post-colonial India, systemic oppression in the form of arbitrary transfers, delayed promotions, exasperating working conditions, and inadequate infrastructure to produce quality work further entrenched the ASI's bureaucratic structure.

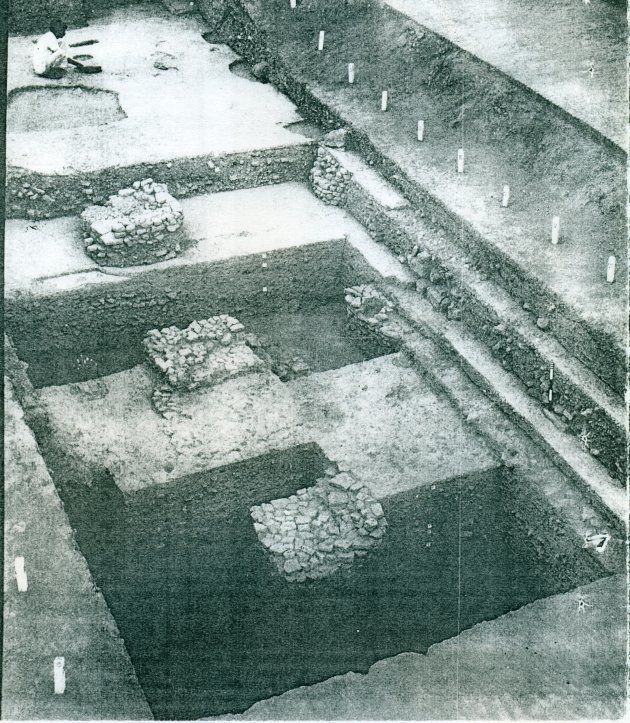

The Ayodhya excavation project solidified ASI's role in shaping the national imagination, actively constructing and preserving a specific form of archaeological knowledge and heritage for the nation. The knowledge monopolisation was further reinforced by the judiciary, and the political executive facilitated a majoritarian vision of a Hindu state. Today, ASI has a pivotal role in furthering the ruling dispensations' political agenda under the guise of 'scientific methods'. Ayodhya verdict is instrumental in cementing ASI's place in the public imagination of nation-building in two keyways. First is the performative nature of the legal truth that has emerged from the courtrooms. Second, it was compounded by the Court's uncritical reliance on the ASI report.

Pillar bases excavated by B.B. Lal (1970s). Photo: Courtesy Supriya Varma

Historian Nayanjot Lahiri critically contends the Court's handling of the Court's handling of ASI in the Ayodhya dispute cases, as an unquestionable authority on historical knowledge, is fundamentally flawed from a research perspective by ignoring the process of peer review. This approach disregarded the credibility and expertise of other scholars, reflecting an intent to monopolise a specific narrative, which directly contradicts the core principles of scientific knowledge production while maintaining the integrity and trustworthiness of the findings.

Lahiri asserts that archaeological research, rooted in scientific principles, typically begins with a set of questions informed by specific methodological approaches. However, as with any field survey, excavations may not always yield answers to the initial inquiries but can instead uncover entirely different findings, which may be equally valuable and intriguing. When excavation efforts become predominantly teleological—aiming to legitimise a particular historical narrative – they establish a hierarchical system of knowledge production driven by political and ideological motivations.

A recent glimpse of ASI’s teleological orientation can be observed in its ongoing explorations of the underwater site off Dwaraka, Gujarat. The project seeks to discover the legend of Dwarka as mentioned in the epic of Mahabharata, where Krishna settled after defeating and killing his uncle Kans, in Mathura. Alok Tripathi, ASI’s additional director general who headed this year’s exploration, asserts the significance of the project from an archaeological, historical and cultural perspective, owing to its mention in mythological literature. He also emphasised the importance of ancient literary sources in the pursuit of historical and archaeological exploration in India.

While earlier phases of exploration conducted in 1963 and 2007 aimed to determine the site's antiquity through an analysis of material evidence, recent years have witnessed a significant shift in the project’s narrative. The focus has gradually moved away from scientifically verifying the age and origin of recovered artefacts toward affirming a mythological truth rooted in epics and legends. This shift was further bolstered by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit in February 2024, during which he offered prayers and described the experience as 'divine.'

Although the ASI has largely succeeded in preserving sites representing India's diverse cultural groups and historical periods since independence, its recent alignment with the state's revisionist agenda is concerning. While the Ayodhya verdict elevated the ASI's prominence as an institution dedicated to restoring the Hindu State, it also revived the longstanding debate on the legitimacy conferred by political authority vis-a-vis the validity derived from its actions and accountability as a public institution. The judiciary's exclusive reliance on ASI's study fundamentally contradicts the principles of polyvocality integral to the enterprise of knowledge production. Moreover, elevating a single institution as the sole authority on historical knowledge, through a closely knitted web of the State, law, and ideological politics, ultimately contradicts the essence of scientific, evidence-based research.

A profound concern is how these developments seek to redefine the constitutional foundation of a secular India by reinforcing an alternative system of knowledge production centred on reclaiming the 'past glory' of India. Under the current political dispensation, ASI is not the only institution that has gradually and systematically lost its autonomy. Research Institutions and public universities are among the other academic bodies drawn to this trend. While state intervention is becoming apparent in these instances, structural concerns also seek our attention.

Unfreedoms

Reflecting on the current state of research and academic freedom in India, political scientist Nirja Gopal Jayal alluded to two forms of unfreedom that hinder critical scientific research: conjectural unfreedom and structural unfreedom. While instances of conjectural unfreedom are becoming prominent in contemporary India in the form of political interference, these tenets reinforce structural unfreedom. Facets of structural unfreedom are enduring characteristics of institutional arrangements which offer lacunae within these democratic institutions for exploitation by other actors.

While democracy provides an essential normative premise for critical inquiry and scientific research, it alone is insufficient. There is an urgent need for structural reforms to keep these institutions away from the corridors of political power by granting greater financial and decision-making independence. Although the ANRF outlines several procedural reforms to address existing barriers to scientific research, the success of these initiatives ultimately depends on the State's willingness to create a democratic environment that supports evidence-based research free from government interference, which will help maintain a vibrant educational and research environment.

What is baffling is that there is very little resistance from the Indian university and academic circles or the Indian science academies against the assault on objective truths, academic freedom and humanistic values. Barring some valiant isolated voices, many choose to be silent and act like willing enablers of the destruction of freedom to think, write and ask questions that foster the creation of new knowledge. India requires a new age renaissance that promotes curiosity, generating new ideas to shape a world that emphasises inclusivity and plurality, and not the old, time-tested, destructive ideologies of the past in new garb.

Swarati Sabhapandit is a Ph.D. research scholar at the Department of International Relations and Governance Studies, Shiv Nadar Institute of Eminence, Greater Noida.

C.P. Rajendran is a geoscientist and a communicator on science, policies, environment and education.

This article went live on May twenty-fifth, two thousand twenty five, at forty minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.