The study of inequality is not just about measuring outcomes; rather, it is shaped by measuring the nature of access available to basic opportunities that enhance human capabilities. This is a basic argument well-secured in both academic and policy discourse for progressive developmental interventions.

With this aim of understanding inequality from the lens of such means or opportunities rather than merely focusing on outcomes, the Access (In)Equality Index Report (AEI) 2025 created by the Centre for New Economics Studies at O.P. Jindal University is a multidimensional index that captures household/individual inequality from the perspective of access to key opportunities. This is the third iteration of the report.

In a two-part series drawing from the report, we explore some of its key findings, including insights from the newly added higher education component within the Access (In)Equality Index 2025.

At a time when the troubled adoption of the National Education Policy in states across India raises issues for certain states, insights gathered from a measured study on access to the (higher) education landscape hold critical value in contributing to the debate on identifying key challenges that merit scrutiny from the respective governments in New Delhi and the states.

Uneven access across states: a national average hiding regional realities

While the national gross enrolment ratio (GER) in higher education stands at 28.4%, this figure masks significant regional disparities.

States like Goa (35.8%) and Haryana (33.3%) outperform the national average, reflecting stronger higher education ecosystems supported by better infrastructure, financial aid programs and institutional reforms. These states have benefited from targeted policy interventions that enhance accessibility and retention in higher education.

In contrast, Bihar’s GER remains alarmingly low at just 17.1%, highlighting deep-seated challenges in ensuring equitable access to higher education. Limited infrastructure, financial constraints and lower secondary school completion rates contribute to this gap.

Eastern and North-eastern states face the greatest challenges

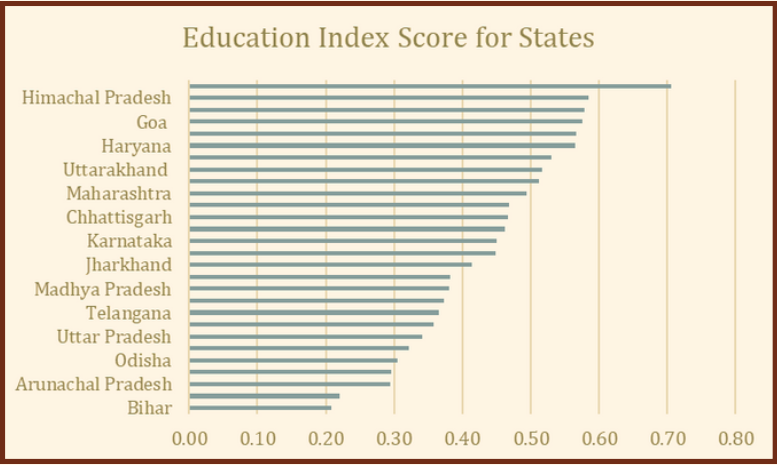

The Access (In)Equality Index ranks states based on key access indicators (with access defined in terms of availability, affordability, approachability and appropriateness), including sub-indicators like pupil-teacher ratios, infrastructure and digital access.

Sikkim leads with a score of 0.71, followed by Kerala, Goa and Himachal Pradesh (0.58 each). Conversely, Bihar ranks the lowest at 0.21, with Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Meghalaya and Odisha also occupying the bottom positions.

These findings highlight severe infrastructural deficits and limited access in the eastern and north-eastern regions, hindering their ability to provide quality education.

Source: Access (In)equality Report 2025.

State-level policies drive performance

Additionally, to facilitate a more granular analysis and comparative assessment, we have focussed on four states: Goa, which is among the best performing states; two middle rankers in terms of performance, Rajasthan and Haryana; and then one of the worst performing states, Bihar. Each state is characterised by distinct policy approaches.

Goa’s success stems from comprehensive financial aid programs, like the Goa Scholar Scheme that allocates Rs 20 lakh for international studies and Rs 6 lakh for domestic education, with a total annual budget of Rs 2 crore. The Interest Free Education Loan Scheme reimburses fees for top institutions, amounting to Rs 1.5 crore annually.

Complementary initiatives like the Bursary Scheme and the Scheme for Promotion of Pure Sciences, alongside digital education and industry-academia linkages, have played a critical role in improving the higher education landscape in Goa.

Haryana focuses on institutional reform through PRaYAAS and gender-inclusive mentorship at the B.P.S. Mahila Vishwavidyalaya.

Bihar prioritises access with significant budgetary allocations and schemes like the Student Credit Card Scheme (loans of up to Rs 4 lakh) and the Mukhyamantri Balika Protsahan Yojana (Rs 25,000 for female graduates) which benefited over 84,000 people in 2020. Notably, Bihar allocated 21.4% of its 2024-25 budget to education, the highest among Indian states.

Rajasthan adopts a rather more balanced approach, combining financial aid with infrastructural development; yet there is a long way to go. The Rajiv Gandhi Scholarship program, with an annual budget of Rs 107 crore, facilitates international exposure, while the Chief Minister Higher Education Scholarship Scheme provides sustained support. Further investments are made in medical education through the Rajasthan Medical Education Society.

Also read: Welcoming Foreign University Campuses Won’t Address Indian Education’s Structural Woes

Budgetary allocations reflect priorities

The broader national trend reflects rising education budgets. The 2023-24 education budget stood at Rs 1.13 lakh crore, marking the highest-ever allocation with an 8.3% increase from the revised estimates of 2022-23 and a 13% rise from the last budgeted figures.

The 2022-23 allocation was Rs 1.04 lakh crore, surpassing Rs 1 lakh crore for the first time, though actual spending was revised downward to Rs 99,881 crore. Of this, Rs 63,449 crore was allocated to school education and literacy, while Rs 40,810 crore went to higher education.

The states have varied yet sustained and strenuous commitments toward education. At one end of the spectrum, Bihar is a state where poor literacy and high poverty levels have seen it allocate its highest-ever proportion of the budget – 21.4% – to education in 2024-25, making the sector allocation the largest yet vis-a-vis any other sector, underscoring its commitment to developing human capital amid financial constraints.

On the other hand, Rajasthan has maintained consistent allocations of about 18-19%. In 2023-24, it set aside 19.7% for education, in which it focussed on institutional reforms, including establishing new medical colleges and enhancing infrastructure through the Rajasthan Medical Education Society.

Goa, too, has a 14.5% allocation in 2024-25, slightly lower than the average of 14.7% by states in 2023-24, and it had significant allocations in secondary and elementary education.

Haryana is investing large amounts in education by providing infrastructure as well as quality improvement through mechanisms such as digital classrooms, teacher-training programs and scholarship schemes.

Spending on education as a percentage of expenditure in select states. Source: Access (In)equality Report 2025.

Systemic change needs a coordinated, multi-dimensional approach

To summarise, even though the higher education domain in India has made some considerable advancement, there is still an urgent need to promote equitable access, gender equity and continuous quality improvement (see a discussion here on this subject).

As argued more recently here, beyond accessibility, deeper, structural problems of both efficiency and equity in improving content and the quality of Indian higher education remains a complex subject of discussion and requires long-term policy planning.

The Indian government has for much of the post-independent era failed to engage sufficiently on these issues, with the Modi government having an indifferent approach to reforming the higher education landscape at a time when youth unemployment has peaked over the last decade.

Short term, quick-fix measures like rolling the red-carpet for welcoming foreign universities to set up elite campuses merely furthers a process of commodification in educational access for a country that is divided by issues of informality, inequality and lack of affordability of quality higher education.

Different state-level interventions from Goa, Haryana, Bihar and Rajasthan serve as useful models for localised policy effectiveness; however, systemic change would require a coordinated, multi-dimensional approach, varying from a focus on increased budgetary efficiency for maximum allocated fund impact, improved digital infrastructure to address regional/intra-state inequities, the adoption of gender-inclusive policies to further female participation starting from enrolment, and the strengthening of industry-academia linkages to boost the employability of those educated at the tertiary level.

Also, the pursuit of academic excellence, built on inculcating constitutionally recognised principles of democratic accountability, public reasoning and impartial critical scrutiny, shall require an urgent dialogue in a federalist system.

Addressing these priority areas would set a pathway towards a more inclusive and impactful higher education system.

Deepanshu Mohan is a Professor of Economics, Dean, IDEAS, and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies. He is a Visiting Professor at London School of Economics and an Academic Visiting Fellow to AMES, University of Oxford. Siddhartha Bhaskar is Associate Professor of Economics at O.P. Jindal Global University. Swati Aggarwal and Achint Kaur are Researchers with IIHED and Aditi Desai and Ankur Singh are Research Analysts with the Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES). The authors thank Najam Us Saqib for his research assistance in documenting the synopsis of the report.

This is the first article about the observations and findings from the latest edition of the Access (In)Equality Index Report 2025.