How India’s Assembly Line Education System Shapes the Perfect H1B Candidate

The first shock of stepping into a US classroom was not the language, the syllabus, or the sprawling architecture – it was the casual defiance of power. Students, headphones dangling, backpacks barely zipped, would rise mid-lecture to take a call or leave without so much as an apologetic glance. Others raised their hands not to pose questions but to remind professors they had overrun their time, setting boundaries rather than deferring to authority. For someone like me, shaped by the rituals of deference and the rigid hierarchies of the Indian education system, this was more than surprising – it was seismic.

Fifteen years later, I can almost empathise with Vivek Ramaswamy’s viral critique of American cultural values. His argument that immigrant engineers thrive because unlike them, American society glorifies the jock over the nerd, almost rings true. It also fits neatly into a familiar stereotype: a disciplined, achievement-oriented “tiger-parent” upbringing juxtaposed against the perceived laxity of the American system, ergo decline in intellectual rigour. Yet, for all the attention his argument garners, it misses something vital about the American classroom – something that cannot be grasped without firsthand experience.

Having worked in the US on an H1B visa and navigating both American and Indian educational systems, I see the flaws in the arguments made by Ramaswamy and others like Musk about the alleged decline in American high-skilled labour. What struck me in those American classrooms was not irreverence or disorder but a different kind of respect – one which, unlike in India, was not conferred by title or demanded through hierarchy but earned through substance. Authority in that space was not imposed; it was invited, tested, and reaffirmed through merit and dialogue. Professors were not exalted for their positions but valued for what they brought to the exchange: expertise, openness, and the ability to inspire thought.

While Elon Musk advocates for expanding H-1B visas for “high-skilled” immigrants, and his stance is at odds with the broader MAGA movement's anti-immigration ethos. It is only fair to look at what makes the American education system unique and why is there an uproar by the tech oligarchs around the need to expand the H1B visa.

American versus Indian system

What does it truly mean to be educated? Is education the moulding of pliant minds into replicas of institutional ideals, or is it the awakening of a deeper self, the nurturing of the ability to question and create?

It begins rather early; step into an American classroom, and you will find an environment free of ceremony: no uniforms and no daily assemblies. A pledge of allegiance does exist, but students can opt out if they want to. Here, identity is shaped not through collective rituals but through the act of questioning – of teachers, of peers, of the world, and ultimately, oneself. The brash jock defying authority or the outspoken rebel challenging norms is more than a cultural archetype; they are reflections of a national ethos. This defiance, often dismissed as glorification of mediocrity, has birthed innovations that reshape the world. The Googles, Steve Jobses, and Zuckerbergs, however polarising, emerge from a system that values risk over rote, intuition over obedience, and audacity over silence.

In contrast, an Indian school assembly is a spectacle of conformity. Rows of children stand in geometric precision, in the morning assembly, designed like a panopticon, under the watchful eye of an authority figure. Every minor deviation, from an untucked shirt to an unpolished shoe, is corrected as though order hinges on uniformity. The march-past exemplifies this ethos – discipline for its own sake, fostering obedience without purpose. Such rituals discourage questioning, embedding a broader societal pattern where authority remains unchallenged.

The American system for example asks you to do a book report on Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and share it in front of your class. This allows a child to look for meanings themselves, an ability to read between the lines, consider, too, the structural fluidity of a system that allows the exceptionally talented child in mathematics to join the advanced class of the grade above or provides remedial support to those who struggle. This flexibility is a recognition that learning is not about conforming to an arbitrary standard but about meeting the individual where they are and guiding them toward where they could be.

Also read: 'Rise of Anti-Indian Hate Posts on X by Trump Supporters is Organised, Systemic Hatred': Report

The Indian cultural ethos that creates the perfect H1B specimen

The Indian system, which produces one of the world's largest pools of engineers, has struggled to make revolutionary impact on global research. Often, it is only when an Indian moves abroad that innovation occurs. When the previous Karnataka government decided to ban hijabs in classrooms, it proved how schools are seen as "qualified public spaces" where individual rights should merge into the collective.

Education in India operates less as a crucible for critical thought and more as a conveyor belt of conformity, its primary test being not how well one can question but how thoroughly one can internalise. The measure of a "good student" is not creativity or innovation but the capacity for disciplined memorisation, and the ability to regurgitate with precision what has been fed. The system rewards obedience to the text, not inquiry into its gaps, and for many, this becomes a lifelong framework. Once a path is charted – whether by parental expectation or societal norm – Indian students tread it with unwavering diligence.

This is not without its triumphs. Consider the dominance of Indian-origin children in American spelling bees. In such arenas, the Indian educational ethos finds its validation. But this same conditioning, which makes us formidable in spaces defined by strict rules and clear answers, erects invisible barriers when the task demands navigating ambiguity, embracing nuance, or asking questions that have no immediate or tangible answers.

We, the Indian science and tech (STEM) kids, remain ensnared in a web of simplistic binaries, our lives shaped from the earliest moments by family structures that demand obedience, caste hierarchies that normalise subjugation, and classrooms that reward quiet compliance. From our first lessons, we are trained to nod in agreement, to affirm the authority that governs us—be it parental, societal, or institutional. This is not education in the sense of expanding horizons but indoctrination into the art of acquiescence. We learn to accept the world as it is, to skim its surface without probing its depths, to absorb its narratives without questioning their origin or purpose.

This conditioning functions with ruthless efficiency. It inoculates us against curiosity, preempts dissent, and convinces us that the visible order of things is not only natural but just. We mistake this facade for equity, believing the world to be inherently fair because we are spared its harshest inequities. This is why figures like Musk, who value efficiency over curiosity, find us so appealing – we do, without question, what is asked.

Training workshops disguised as universities

A 2017 CSDS-Lokniti report found that higher education levels in India correlate with stronger right-wing authoritarian views. Educated individuals showed the highest support for punitive actions on divisive issues like beef consumption and religious conversions, with many endorsing mob violence, dictatorship, and the suppression of free speech – stances less common among the less educated.

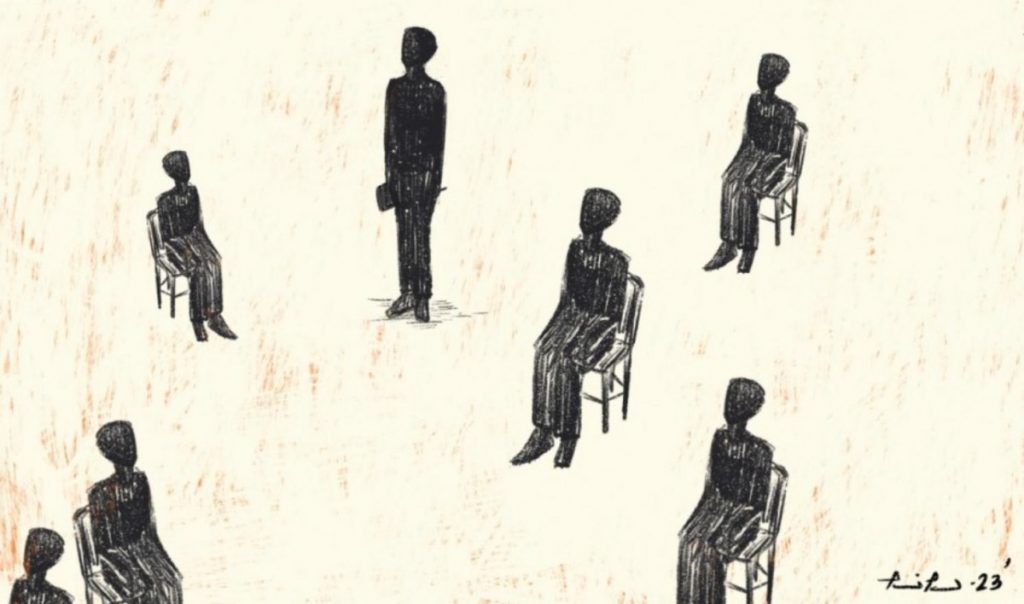

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty.

During my graduate school years in the US, classes and exams often felt like workshops – collaborative, exploratory, and, at times, almost chaotic. Teachers wielded flexibility like a tool, adapting lesson plans to the moment, while students were afforded the freedom to chart their own academic paths within the framework of their chosen degree plans. This autonomy was not just a logistical feature; it was a philosophical cornerstone. What emerged was a system built on choice, negotiation, and mutual respect. The American classroom was not a temple where one bowed to the infallible teacher but a space for dialogue, experimentation, and even dissent.

But to create something new, one needs a certain amount of rebellion. The many Indian startups are an example of this vacuum. Few of the known Indian startups are original creations – from the ride-sharing apps to the food-delivery apps. The only ones that are somewhat original are those 10-minute grocery delivery apps which are a means for this same “educated” and rich upper class to exploit the cheap labour available all around. It is no surprise that many of these startup founders are also ex-H1B graduates.

In India, at 16, an Indian student pursuing technical education severs any ties with the liberal arts, cutting off their only avenue for grappling with ethical dilemmas or societal complexities.

These technical training institutes, unlike their Western counterparts, are not full-fledged universities, they have a limited focus and there is hardly any multi-disciplinary academic programme that allows for technical education to be complimented with any broader inquiry that can come from association with other academic streams. They do not foster philosophical inquiry or political debate. They function more as workshops, designed to produce efficient workers, not critical thinkers, cultivating a narrow conformity.

Students at these colleges, like me, are trained to see the world in binaries of questions and answers. There is no grey area of abstraction. Politics, if it appears at all in our lives, stems either from the unquestioned authority in the home or the curated algorithmic echo-chambers of social media – spaces inhospitable to the disruptive spark of a foreign idea. So, without the messy friction of diverse thought, the Indian techie becomes a semi-autonomous machine, programmed for specific tasks, but untouched by the forces of diversity. Therefore, our 'upper' caste, middle class global aspirations make us hugely suitable to the American H1B factory line. Our education system has primed us for productivity, not introspection, fostering a mindset that aligns much better with authoritarianism than liberal pluralism.

The flaw in Ramaswamy’s critique lies in its failure to recognise this nuance. The American system’s lack of rigidity is not a bug but a feature, fostering innovation precisely because it values questions over answers and boundaries over blind obedience. It is not perfect – no system is – but its willingness to embrace disorder and dissent has birthed some of the world’s most revolutionary ideas. What Ramaswamy perceives as weakness is, in many ways, the source of its strength.

So, yes, H1B is great for the American oligarch because it allows them to hire cheap automatons much like me. But is it a better system of imparting education than the American one? The answer is a hard no, bro.

Raj Shekhar works in the area of data privacy regulations. He also occasionally contributes as a freelancer writing on politics and runs a podcast on politics called the Bharatiya Junta Podcast.

This article went live on January eleventh, two thousand twenty five, at nine minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.