School and university education in India increasingly looks like a dented football kicked around randomly by amateur players. A party comes into power, and the first thing it does is to ban certain subjects and historical figures from the curricula, and replace them with its own preferred leaders. The latest to play this game is the newly elected Congress government in Karnataka.

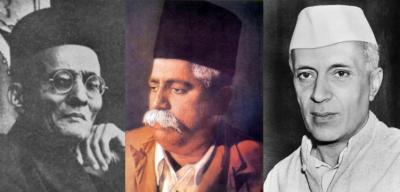

Ministers of the government have decided that K.B. Hedgewar and V.D. Savarkar will not be taught in schools, and that the name of Nehru will be catapulted onto academic curricula once again, along with other leaders who had been banned by the previous Bharatiya Janata Party government.

This is obviously a prime case of political retaliation, but it is, nevertheless, a naïve decision. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which Hedgewar founded, is not going to go away from our lives simply because schools will not teach the ideas of the founder. And Nehru will not disappear from our collective consciousness just because the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library has been renamed, rather unimaginatively, as the Prime Minister’s Museum and Library.

Witness the irony. Across the world, reputed research centres and libraries are named after seekers of knowledge such as the philosopher Goethe. In India, NMML, a once renowned centre of research and academic discussions, is now renamed after seekers of power!

Also read: No Country for My Nationalism

Back to school

To come back to school education, the problem is not only in the way in which certain leaders are brought in, and others dropped, but in the teaching of history itself. History is not a laundry list of leaders without their context, and without reference to other political figures who also impacted history well, badly, or indifferently. Multiple events happen at a moment in time, and the task of the teacher is to link discrete happenings and thereby present a pattern to the student.

Instead of presenting students with a grocery list of leaders, suppose teachers introduce them to the complexities and the contradictions of their context-nationalism as a modern ideology, first invented in France and Italy in the 18th century. In the context of colonised India, nationalism gave to a people, otherwise removed from each other by geographical distance, and distinct regional cultures and languages, a shared identity. But nationalism is not a singular or a coherent ideology which creates ‘one nation’ endowed with the right to self-determination.

Like the proverbial amoeba nationalism proliferates, generating different histories of the nation, and resolving the question of who should inherit the post-independence nation differently. In India the national movement ranged from the religious right to the secular left. Unfortunately, plurality is seldom marked by harmony; it is more likely to generate intense and often irresolvable contestation.

Some nationalists conceptualised the nation as the product of a syncretic culture and as inclusive and egalitarian. Others believed that the nation belonged to only the majority community by reasons of numbers. Nehru subscribed to civic nationalism, and Savarkar was committed to ethnic nationalism. The philosophical presuppositions of each were different, the implications of their commitments were dramatically different.

Nehru’s notion of the nation can be judged as inclusive and democratic only if we counterpose it to majoritarianism. That is why we cannot teach a national figure in isolation from his contemporaries, and from rival nationalisms. Moreover, a comparative study of different types of nationalisms might bring home to the student the importance of inclusion, of accommodation, and of democracy. After all the nation remains contested.

Also read: 19th Century’s Hindu Nationalism Was Flawed but Had Purpose. Now, We Have Only Hate

Need comparative method, not removal

Removing X or Y from the syllabi will hardly enable teachers to emphasise the significance of the comparative method. Through the comparative method that weaves different strands of the past into a pattern, students will learn that history proceeds through the negotiation of contradictions, that the outcome of history is not dictated by individuals but by ideologies, and that history tells us a story of how contestations were handled; sometimes well, sometimes badly. Above all they will learn that we should learn from history, that there are certain things that should not be done to human beings, and there are certain things that should be done for them.

Build critical minds

For this we need to understand that education is not meant to produce cogs in the wheel of the capitalist machine, or mindless supporters of ruling ideologies. Education is expected to produce informed minds which can critically engage with the past and with current events. The development of critical faculties is the main marker of an educated mind.

There is no substitute for a questioning mind. For it is only the critical mind which knows the difference between the right kind of nationalism that gives to its people not only an identity but also a political community in which they accept others as equal, and the wrong kind of nationalism that calls for extermination of others on indefensible grounds. This they will not learn if they are taught only certain leaders and not others.

We can only accomplish this objective if politicians leave education to the educator. Those who teach must be in control of what is taught and how it should be taught. Education is too complex and too important to be left to politicians, especially those who cannot stand questions about the way they govern, and who jail dissidents. We have to rescue education from the holders of power. Otherwise at some point in their career, students will continue to turn their backs on the educational system in India, and flock to universities abroad, even in countries not particularly known for academic excellence.