In a Ranking-Obsessed System, What Exactly Are Universities Competing For?

In higher education, global rankings operate as more than scoreboards, they are a powerful instrument to shape perceptions, guide policy decisions, and influence where students wish to study and where governments place their investments. Among the most popular ones are the QS World University Rankings by Subject, published every year and designed to assess university performance in particular academic disciplines.

These rankings are no longer seen simply as measures of academic reputation or research prowess but increasingly as benchmarks defining international competitiveness in education. They are taken into serious consideration in government policymaking, often determining funding priorities and serving as a roadmap for institutional changes in a country’s higher education landscape.

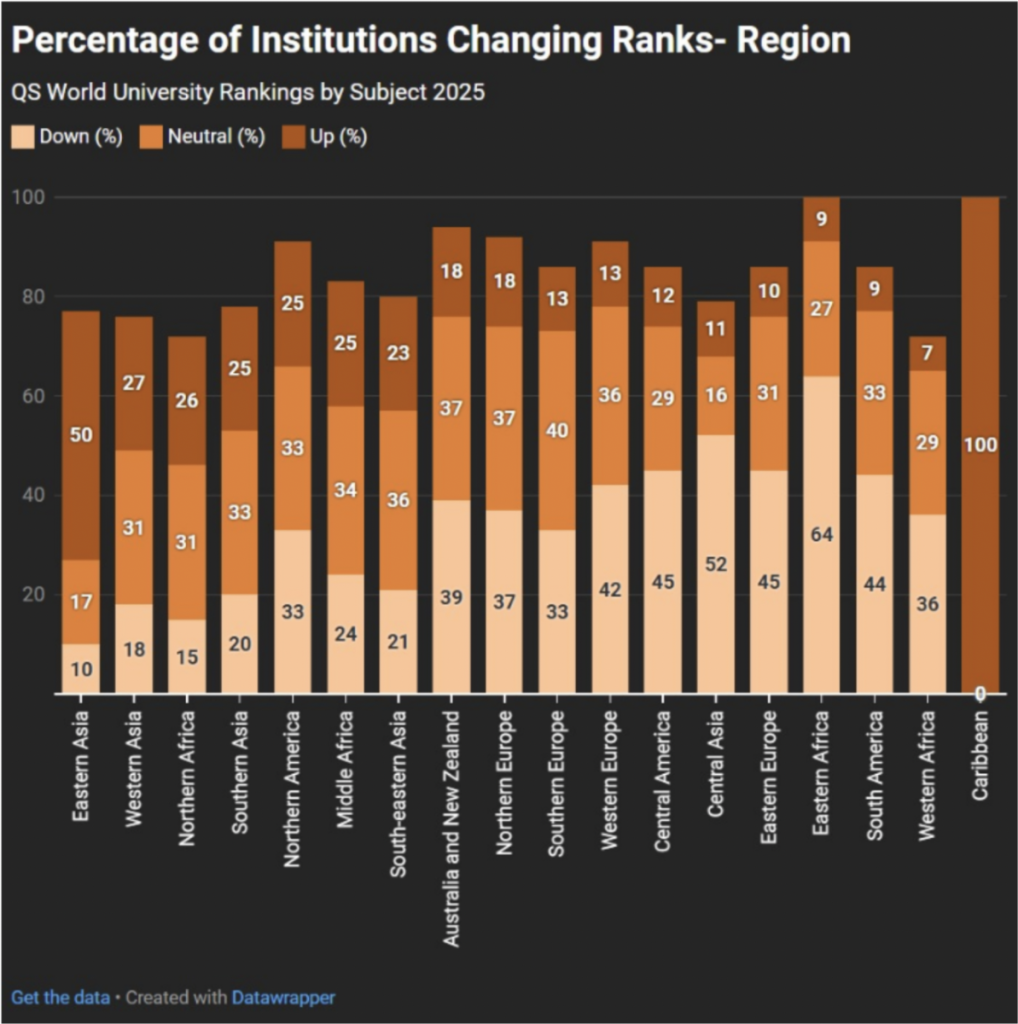

On March 12, the latest edition of the QS World University Rankings by Subject was unveiled. This year’s edition assessed over 55 subjects across five broad faculty areas – a significant expansion that reflects the growing complexity and specialisation of academia.

Notably, 171 institutions entered the rankings for the first time.

Medicine, computer sciences, and materials have witnessed a substantial increase in the number of ranked institutions across the globe, which is indicative of not only expanded academic capacity but also aggressive strategic competition among universities to increase their reputations in high-demand and innovation-oriented areas.

For instance, Computer Science ranked institutions went up from 601 in 2020 to 705 in 2024, while Materials went up from 350 to 460 institutions in the same period. This quantitative growth reads as more than just academic interest; it signals a worldwide sprint for visibility in fields that are now major funding, patenting, and policy-influencing drivers.

Source: QS World University Rankings by Subject 2025.

We observe emergence of Western Asian and Arab institutions into prominence, particularly in STEM and social scientific fields. The upgrade in engineering, business, and medicine programmes amongst institutions in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar is revealing.

According to QS data, King Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia jumped from a ranking of 12 programmes in 2019 to 32 in 2024, with at least five in the global top 100. Likewise, United Arab Emirates University, which entered the ranking of the top 300 in Business and Management in 2023, has improved its performance drastically in rankings.

While this dramatic increase might truly represent investments made in the R&D infrastructure, it has also raised some doubts.

Rankings are now based on the indicators like academic reputation (40%), employer reputation (10%), research citations per paper (20%), and H-index (20%), further endorsed by the score of the international research network.

Although these inputs are presented as robust, they remain amenable to strategic calibrations. Over the years, universities in some parts of the world have geared their maturity towards these indicators, for example, citation clustering, having globally renowned adjunct faculty, or even vigorously participating in international reputation surveys.

Questions then become less about how meritocratic mobility is attained and hinge more on whether some institutions have become good practitioners of rankings-oriented institutional engineering. The divergence in assessment serves as a useful example.

Academic reputation scoring diverges sharply from citation metrics. In certain countries, like Singapore and Saudi Arabia, institutions have found reputation scores that grew disproportionately compared with citation growth an issue flagging possible nefarious reputation management activities.

Such patterns can raise questions about whether the QS Subject Rankings are growing disciplinarily dated and promotionally orientated, rewarding rank-savvy strategies as opposed to authentic progress in scholarship.

Impact

Yet they continue to impact national higher education policies, especially in the emerging economies, where appearing within the global top-200 is increasingly equated with financial support, recruitment of international students, and bilateral academic diplomacy.

A key concern with the QS Subject Rankings lies in the disproportionate weight assigned to academic and employer reputation surveys, which together account for up to nearly 50% of the overall ranking score in many disciplines, particularly in the humanities, business, and social sciences.

The academic reputation survey, contributing around 30-40%, is based on responses from academics asked to name top institutions in their field, while the employer reputation survey (10-15%) captures perceptions from industry professionals regarding graduate quality.

Although these surveys are global and normalised by region and discipline, universities often influence the process by nominating employers or encouraging affiliated academics to participate, creating space for subtle lobbying and curated visibility.

In the meantime, universities are able to tactically pursue self-referencing in the form of collaborations with highly cited scholars or even get involved in citation rings – all of which are able to contribute to a synthetic boost of their research influence.

Rankings like QS openly claim to reflect global academic excellence, yet mostly favour visibility above substance, reputation above rigour and metrics above mission.

Because they are dependent mainly on citation counts and subjective surveys, they neglect context-specific contributions such as teaching quality, community engagement, or equity in access, which are at the heart of the societal role of a university. Hence, they run the risk of incentive creation to institutions to adopt ranking-friendly behaviours such as aggressive international hiring, branding exercises, or citation engineering rather than digging deep into long-term academic development.

One can even make the race up the rankings look like a strategic game.

Retractions and reputation manipulation

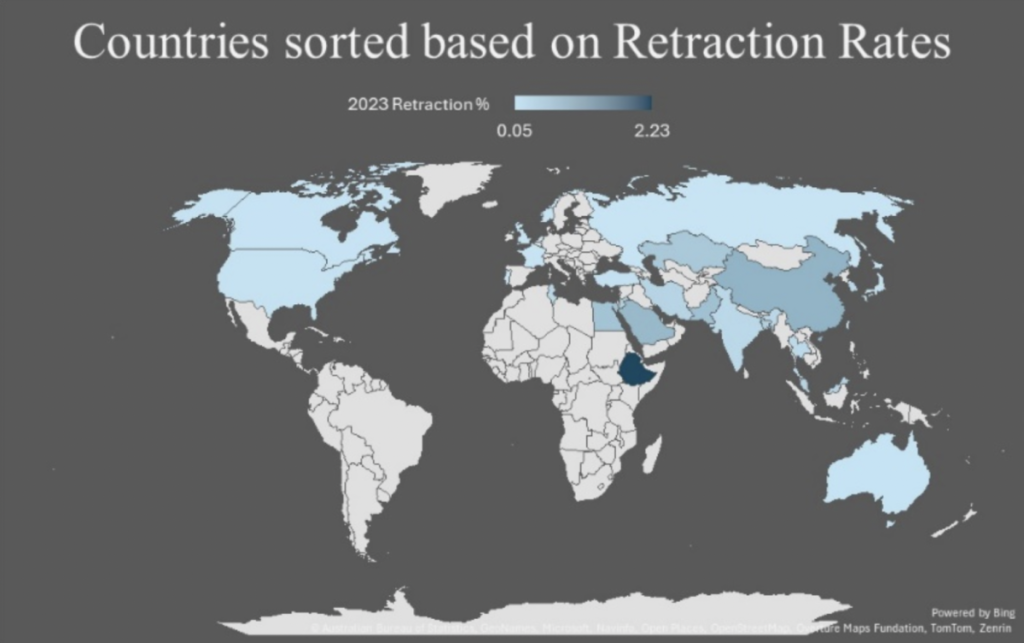

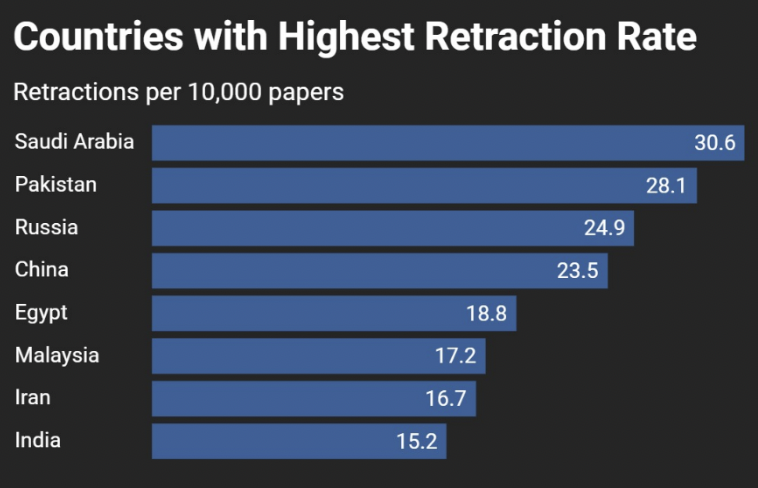

While universities are pursuing ever-rising QS ranks, an ominous trend is rising from some of the most rapidly improving institutions from nations with distressingly high retraction rates. Review of global retraction data spanning 2022 to 2024 indicates a high correlation (0.85) between the increase in publications and increase in retracted studies.

A closer examination of the data reveals a geographic clustering of high retraction countries mainly in Asia, West Asia and Eastern Africa. China, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iran are the nations where publication numbers have skyrocketed while retractions have caught up at a frightening rate.

China alone recorded 14,381 retractions between 2022 and 2024, the world's highest, followed by India with 2,325 retractions, an indication of its fierce thrust in scholarly production. Pakistan also with 626 retractions followed closely with Saudi Arabia with 1,174 retractions, and Egypt with 518 retractions also prominently figure replicating their explosive surge in QS rankings across several fields.

Source: India Research Watch.

The figures indicate that institutions in these countries might be taking advantage of the ranking system that gives heavy emphasis to research productivity and citations. Although not all retractions are due to research misconduct an overwhelming majority are associated with fabrication, falsification or duplication reflecting systemic problems within these higher education systems.

Saudi Arabia, for example, had its number of publications increase by over double from 27,088 articles in 2019 to 63,798 in 2024, and no surprise that its retractions have increased exponentially which clearly indicates that this rapid growth might not be all natural. Likewise, Pakistan boosted its publications by over 50% during the same time with a corresponding spike in retractions.

Source: Total number of research papers according to Scopus: articles and reviews. Analysis excludes conference papers (and their retractions). Retraction numbers have been taken from Retraction Watch Database, SCImagoJR.

Compounding the situation is the inconsistent enforcement of academic honesty across regions. In Western countries such as the United States, Germany, and the UK, where policies on retraction are tighter and penalties for misconduct more stringent, universities seem less susceptible to inflationary publishing practices.

Due to its dependence on research output and citations, the QS system unintentionally favours quantity over quality. Universities that want to rise in the rankings produce enormous amounts of research, frequently without the facilities necessary to guarantee quality control.

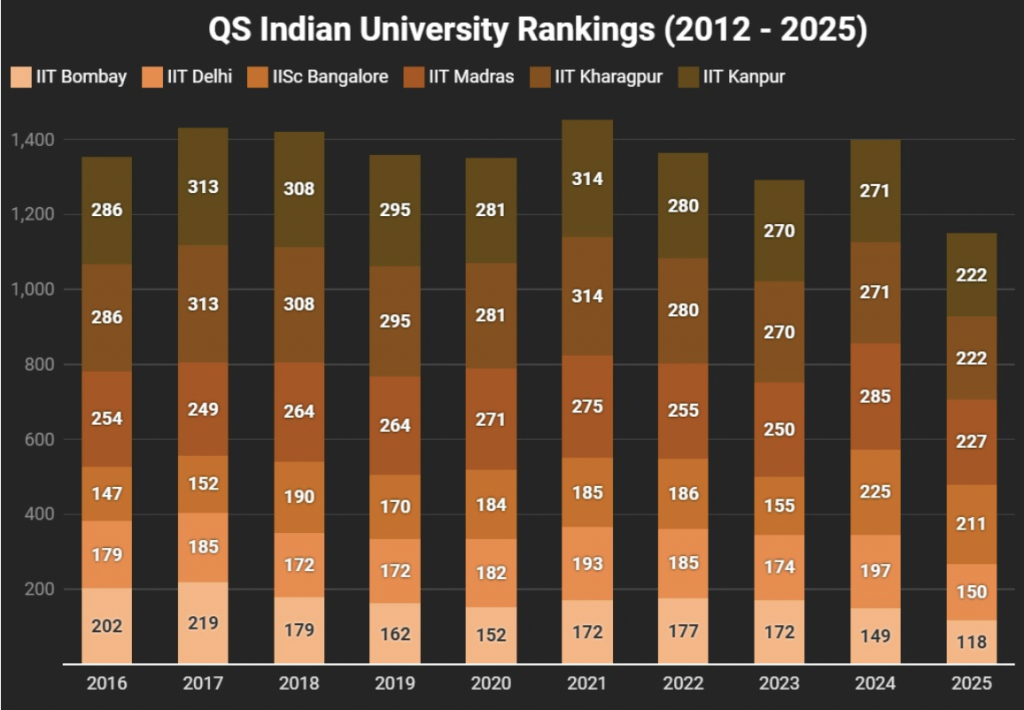

India’s meteoric rise

India's policy landscape has become hostage to the seductive tyranny of global ranking systems, with the 'Institutions of Eminence' (IoE) scheme standing as a prime example. Launched to propel a few universities into top global ranks, the scheme reeks of elitism disguised as ambition. Crores have been poured into select institutions, while underfunded state universities with overstretched faculty and broken infrastructure receive little attention. In 2024-25 the allocation for higher education saw a decrease of 17% from the revised estimate for 2023-24, yet IoE institutions continue to hoard grants, some of which remain unspent due to bureaucratic delays. This rankings-driven model deepens inequity, cementing a caste system in academia where IITs flaunt global tags and rural colleges struggle for basics. NEP 2020’s 50% GER target by 2035 rings hollow when resources chase vanity metrics over meaningful reform. What India needs is decentralisation, not Delhi-Mumbai showcase projects.

India's sharp ascent in global university rankings has been hailed as a symbol of its emerging academic strength. But beneath this optimistic narrative lies a more complex reality.

Source: QS Rankings.

India has significantly expanded its research output, with publications rising from only 185,439 papers in 2019 to an estimated 290,823 in 2024 that represented a more than 56% increase. This growth came at the same time that India's education budget increased by 51.33% since FY19, an indication of the government's initiative towards higher education.

However, with a mere 6.5% hike in the Union Budget for 2025-26, India's overall expenditure on education continues at about 4.6% of GDP, much below the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020's vision of 6%. Japan, to compare, spends 7.43% of its GDP on education, and Germany, despite budget restrictions, spends 4.6% on primary and tertiary alone.

This gets reflected when we critically analyse India's rise in the QS Subject Rankings particularly in STEM fields like engineering, computer science, materials science, and medicine coincides with QS’s increased emphasis on research citations per paper and international research collaboration. These indicators have allowed institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), and even emerging private universities to climb in rank, given their focused efforts on improving citation metrics and international co-authorship.

Both Union and state governments have increasingly weaponised favourable university rankings as political capital, brandishing them as symbols of progress while deliberately obscuring the crumbling foundations of India’s higher education system. These rankings are often paraded in press releases and policy briefings, serving more as public relations stunts than as indicators of systemic improvement. The reality is far grimmer: public universities continue to suffer from chronic underfunding, alarming faculty shortages, and administrative apathy. Regional imbalances remain stark, with institutions in several states still lacking basic infrastructure, let alone global ambitions. As mentioned in the AEI report, this uneven investment not only limits access but also reinforces socio-economic hierarchies within the academic landscape.

This performative obsession with rankings incentivises cosmetic reforms over structural transformation. Funds are funnelled disproportionately to a few elite institutions in a bid to polish international profiles, while the rest of the academic ecosystem remains neglected and unequal. The push for better rankings has also dovetailed conveniently with the neoliberal project of privatisation which allows the state to retreat from its obligations under the guise of global competitiveness.

Moreover, methodological changes in QS such as greater emphasis on international collaboration and the introduction of new indicators like sustainability (in the overall rankings) have favoured urban, English-speaking, internationally connected private universities, while state universities and regional public institutions have struggled to keep pace.

This has led to a widening of gap within India's own higher education ecosystem, privileging institutions with global networks and reputational capital, rather than those serving broader domestic needs.

In summation...

There are a lot questions with methodological origins of vital metrics that have serious, consequential policy outcomes. QS, THE and similar other metrics in higher education performative mapping, despite their strengths and weaknesses offer useful comparative studies. But, these may also be misleading. Universities have a responsibility to recognise the limitations of a ranking-obsessed policy ecosystem and must also focus on endogenous areas of quality, integrity, and social utility, whereby meaningful contributions to research also take precedence over metric-driven optimisation.

Deepanshu Mohan is a professor of economics, dean, IDEAS and director, Centre for New Economics Studies. He is a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and an academic visiting fellow to AMES, University of Oxford.

Aditi Desai and Ankur Singh contributed to research.

This article went live on April thirteenth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.