How Satellite Images Contradict Himanta Biswa Sarma's Claims on Rat-Hole Mining

Just a few days after nine workers were trapped and killed in a rat-hole coal mine in Assam, in January this year, the state’s chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma was quick to claim that the mine where the accident occurred had been abandoned for years.

Since 2014, when the National Green Tribunal (NGT) first banned rat-hole coal mining, the state government claims to have cracked down on such mines on several occasions. A satellite imagery-based investigation, however, shows that unchecked illegal rat-hole mining was being carried out not only at the accident site, but also in its surrounding areas for several years, with the administration looking the other way. In fact, several illegal rat-hole mines were found to be operating at a coal-mining block administered by the state’s own mining corporation, raising serious questions on the government’s ability to stop the illegal mining.

On January 10, 2025, four days after nine labourers were trapped in a flooded rat-hole coal mine in Assam, Sarma held a press conference to address the tragedy. Sarma categorically denied any prior mining activity at the site, stating, “AMDC [Assam Mineral Development Corporation] abandoned all these mines twelve years back.”

He added, “These people entered the mine that day for the first time, to extract coal. And before that, there was no mining on that site.” Rat-hole mines – small, narrow tunnels used for coal extraction, just large enough for a single worker to crawl through – were banned by the NGT due to the environmental damage they cause, the unscientific processes involved and the highly hazardous nature of the mining itself.

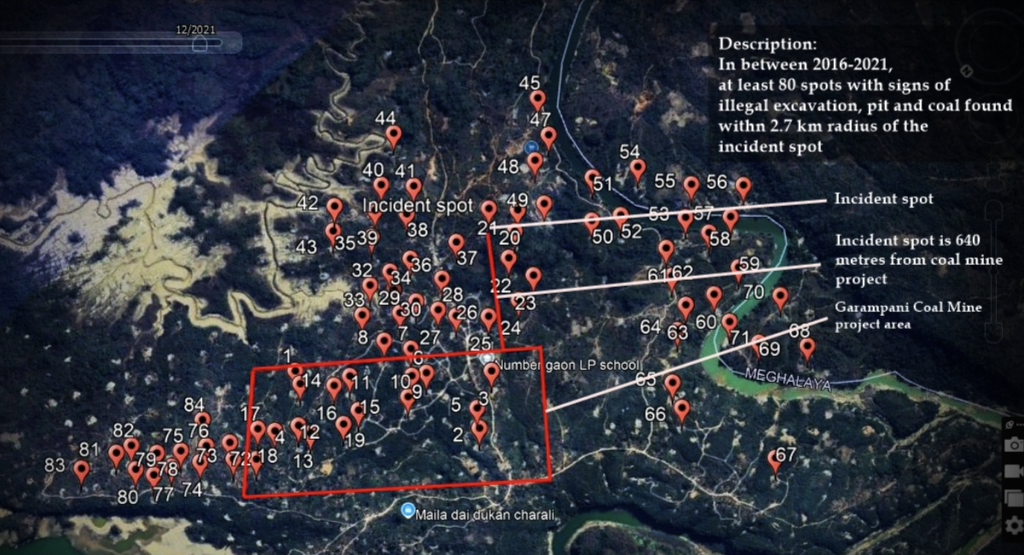

However, this reporter's investigation, using satellite images from Google Earth, reveals rat-hole mining at the specific site of the accident since at least September 2021. In fact, over 80 rat-hole mines exist in a radius of 2.7 kilometres around the accident site – the earliest of these have been operational since at least 2016. All of them are illegal.

Interestingly, parts of the area surrounding the accident site come under the Garampani coal mine, which was allotted to the AMDC in 2022. The accident site is a mere 640 metres from the Garampani coal mine. Out of the 80 rat-hole mines this reported spotted, at least 19 mines are within the limits of the Garampani coal mine.

Apart from the existence of several illegal rat-hole mines in the Garampani coal mine, a 2022 Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report had flagged irregularities in AMDC’s previous operations in the area. From 1984 to 2021, the AMDC operated the Garampani Coal Extraction Project (GCEP), spread over 500 hectares, in the Dima Hasao district. As per the CAG, AMDC’s mining operations in GCEP, from 1984 to 2021, were unauthorised as the company did not have multiple clearances or even valid mining leases. In 2022, the Garampani Coal Mine – spanning 109 hectares – was auctioned. AMDC won the bid but it still does not have operational clearances for the project, making any mining activity illegal.

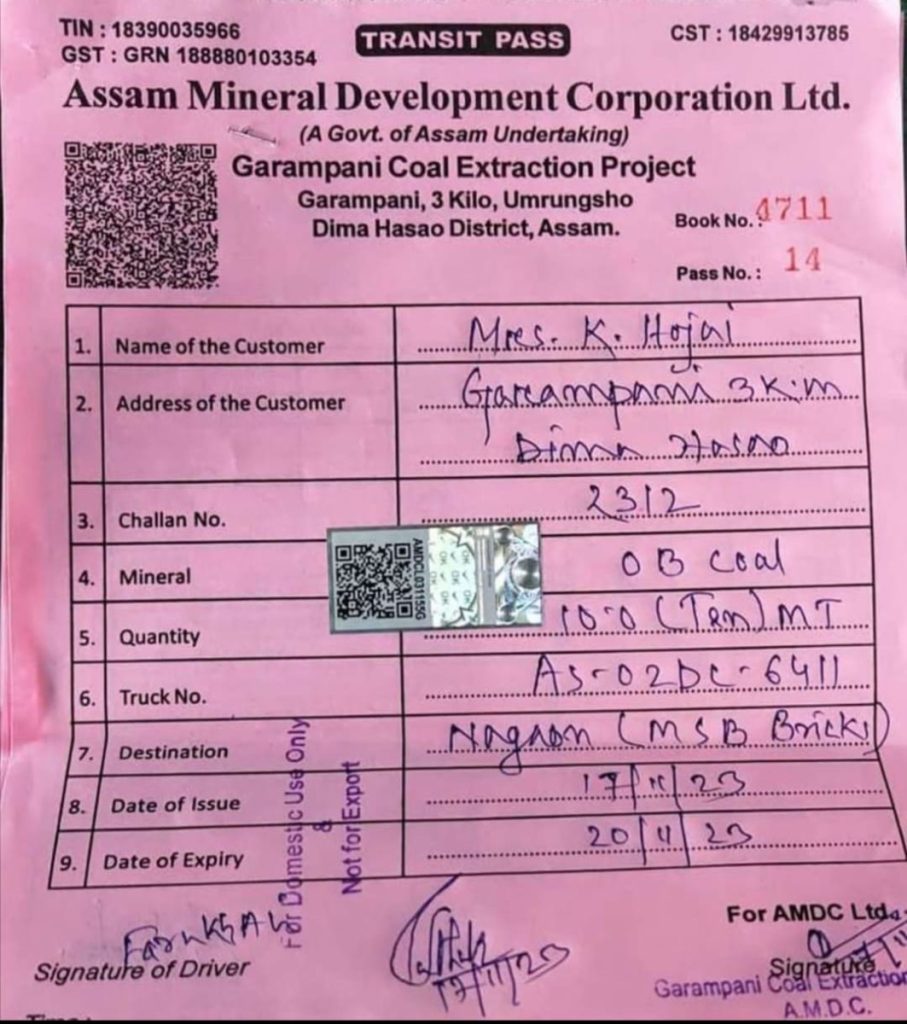

A “transit pass” – a pass for transport of mined coal – from near the accident site, dated September 2023, was issued by the AMDC for GCEP, for a site identified as “3-kilo.” An NE News report claimed that the pass was issued to an individual allegedly linked to an influential BJP leader.

None of the nine men trapped in the rat-hole mine at the site in the Umrangso area of the Dima Hasao district survived, and it took 44 days to retrieve all nine of their bodies. But their deaths are not an isolated incident in Assam. For instance, in just the years of 2022 and 2024, the district of Tinsukia reported at least seven deaths due to three accidents in illegally operated rat-hole mines.

Despite years of mining-related deaths, the Assam government acted only after the January accident, by initiating the sealing of 250 illegal mines amid public and political pressure. A judicial enquiry and a police Special Investigation Team (SIT) probe was also ordered into the incident. Opposition parties and local activists allege that the Assam government is responsible for the accident as it has deliberately neglected rampant illegal mining in the area and other districts of the state.

This reporter wrote detailed emails to the chief minister Sarma and AMDC’s managing director Natarajan Anand with questions on the findings and allegations. They are yet to respond.

What images say

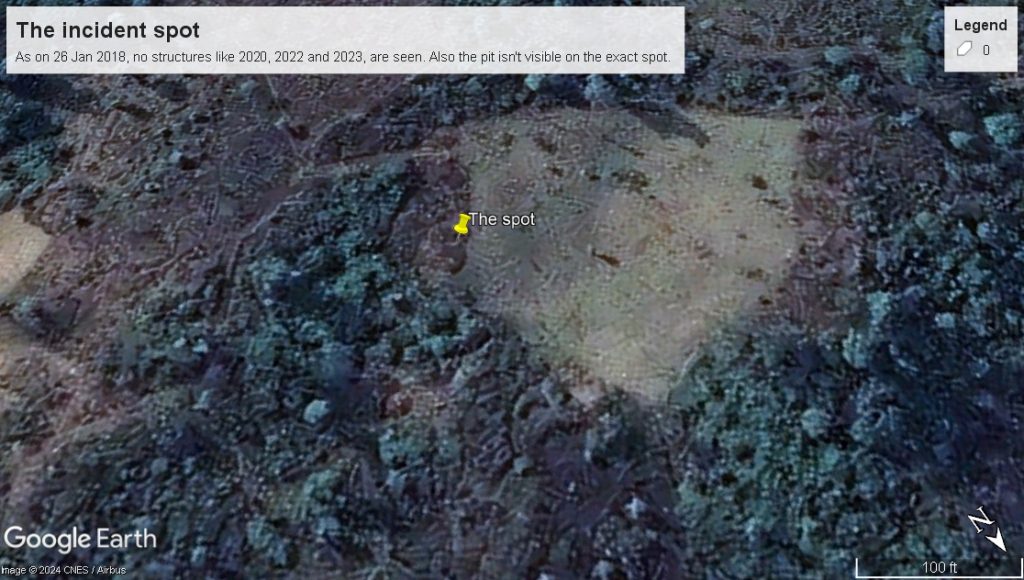

At the press conference, Sarma made two major claims: the day the incident happened was the first day workers entered the mine; and there was no mining on the site before that.

In addition, satellite images of the nearby Garampani coal mine – 640 metres from the accident site – show clear evidence of mining, rat-hole and otherwise, since at least 2016.

A review of satellite images show illegal coal mines in locality over the years, from 2016 to 2021.

The images showed excavation and rat-hole mining pits, and the presence of coal in at least 80 such spots within the radius of 2.7 kilometres of the incident spot. This includes at least 19 such spots within the 109 hectares of the Garampani coal mine. All these spots, as seen in satellite images from 2016 to 2021, follow a similar pattern: first, signs of excavation appear; then, pits become visible, and eventually, coal is seen near the pit.

Comparative timeline of the accident spot:

Who is Debolal Garlosa and his connection to the case?

Curiously, on January 10, the same day the CM made the claims about the mine, Sarma also clarified that a local BJP leader, Debolal Garlosa, was not named in the police investigation. Garlosa is the chief executive member (CEM) of the Dima Hasao Autonomous Council.

An influential figure in the region’s local politics, Garlosa has been in the news recently due to protests against his leadership by the BJP’s cadre, who want him ousted as the CEM. The party’s cadre accused Garlosa of “corrupt practices” and being a “land mafia.”

The transit pass issued to 'Mrs K. Hojai'.

Garlosa’s connection to the Umrangso tragedy is centred on the “transit pass” mentioned earlier, revealed by local news reports between January 8 and 10. The pass in question was issued by the AMDC, for the GCEP, in the name of “Mrs K. Hojai”. Garlosa’s wife’s name is Kanika Hojai. The transit pass was issued on November 17, 2023, for a consignment of “OB coal” – overburden coal, which is the material found above coal seams. The pass was issued for the same site – called “3 Kilo” – where the current accident occurred.

In April, Dima Hasao Chief Judicial Magistrate S. Chanda ordered the police to register a case against Kanika Hojai in connection with the mining tragedy that resulted in the deaths of nine people. An FIR was then registered.

AMDC’s role under the scanner

While the transit pass itself does not give any indication of which mine it was issued for, there are two key issues with it.

To begin with, according to the union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s Parivesh website, the AMDC does not have environmental clearance for coal mining in the Garampani coal mine. This implies that any AMDC coal mining activities in the region, before such clearance is granted, are unauthorised.

Secondly, according to media reports, Kanika Hojai is an “approved customer” of AMDC. Approved customers excavate and transport the coal. But, as the CAG report pointed out, this was in violation of the lease agreement between AMDC and the state government, according to which the company had to conduct mining operations themselves.

The AMDC has a chequered history with the Garampani coal mine. The CAG report from 2022 stated that from April 1984 to January 2021, it conducted illegal mining at the GCEP. According to the CAG report, the company did not have a valid mining plan, lease agreement and environmental clearance. In 2022, when the Garampani coal mine was auctioned, AMDC won the bid. But since AMDC does not have clearance for the project, it is unclear how it issued a transit pass.

State complicity?

In the days following the accident, the state police arrested five individuals. On January 16, the superintendent of police of Dima Hasao said that three of the arrested individuals were the supervisors and financiers of the illegal mine.

On January 19, the state government initiated the sealing of illegal rat-hole mines. By then, there had been significant public uproar surrounding the deaths of the nine men.

Illegal coal mining in Assam has long been a concern raised by activists and politicians. A 2022 probe by Justice Brojendra Prasad Katakey found that North Eastern Coalfields (NEC) illegally extracted Rs 4,872.13 crore worth of coal in eastern Assam without mining rights. A 2017 CID report also revealed illegal coal transportation for years with the involvement of police, politicians, and Coal India Limited officials. Despite clear evidence, illegal mining persisted, with the Assam BJP government failing to take serious action until the latest incident sparked public outcry.

Daniel Langthasa, a former NC Hills Autonomous Council member, blamed the state government. “Administration has clearly helped it to flourish, especially since 2016-2017.” Langthasa added, “Everyone was working behind the scenes, working together in this illegal activity.”

This article went live on May twenty-third, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-two minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.