Wildlife Conservationist Anne Wright Passes Away at 94

The recent death in central India of Anne Wright, age 94, marks the end of an era. This wildlife campaigner, tiger enthusiast, horse breeder, party lover, and friend of leading politicians and royalty, was one of the last of the British expatriates who stayed on after independence in 1947.

Anne Wright died on October 4 after a long illness at her family’s Kipling Camp jungle resort on the edge of Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh. She was cremated, as she would have wished, in the jungle later that day under the stars.

In 1929, she was taken when she was just a few months old to the wilds of central India where her father, Austen Havelock Layard, who was in the Indian Civil Service, was posted. She spent the rest of her life in the country, apart from schooling in the UK, and took Indian nationality in 1991.

One of her early memories was standing, when she was five, with her younger sister and governess on the Kings Way (later Rajpath and now Kartavya Path) in New Delhi. Wearing large white topis (sun hats), they were watching her father, by then the city’s deputy commissioner, process past with the Viceroy Lord Willingdon in 1934.

Anne Wright. Photo: sanctuarynaturefoundation.org

At Mahatma Gandhi’s cremation in Delhi in January 1948, she sat with members of the family of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last British governor general. She remembered being terrified by the vast sea of people. While visiting her friend Rita Pandit, prime minister Jawaharal Nehru’s niece at his Teen Murti residence in Delhi, they went into his bedroom where she saw a photo of Edwina, Mountbatten’s wife, on the bedside table – poignant evidence of the Edwina-Nehru relationship.

It was a grand life. She told John Zubrzycki for a book he was writing on the Jaipur dynasty, how as a young bride in the 1950s she had gone as a guest of the royal family to the princely state of Cooch Behar in what is now West Bengal. At the age of 90 she could “still vividly recall landing on the state’s grass airstrip in the dilapidated DC3 being operated by Jamair”. On arrival, “guests would be met by elephants that would transport them and their luggage to the palace.”

A small, slight and elegant lady with a winning smile and sparkling eyes, she could be tough and determined. She showed this in an extraordinary exchange of letters asking Indira Gandhi, India’s prime minister, to lobby Pakistan’s and Afghanistan’s leaders at a Commonwealth summit meeting in 1983 about the plight of the Siberia cranes.

Gandhi was sceptical about the prospects, but later told Wright both countries had agreed to take protective measures.

Jairam Ramesh, an Indian policy adviser-turned-politician, says he “spent hours” with Anne researching his book, “Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature”. He writes that “an ecstatic Anne Wright” replied to the prime minister, and raised yet another subject – tapping a major river, the Teesta in north east India to save the Neora Valley. Gandhi later congratulated her on the work of World Wildlife Fund – India, of which Wright was a founder trustee in 1969.

Anne Wright. Photo: kiplingcamp.com

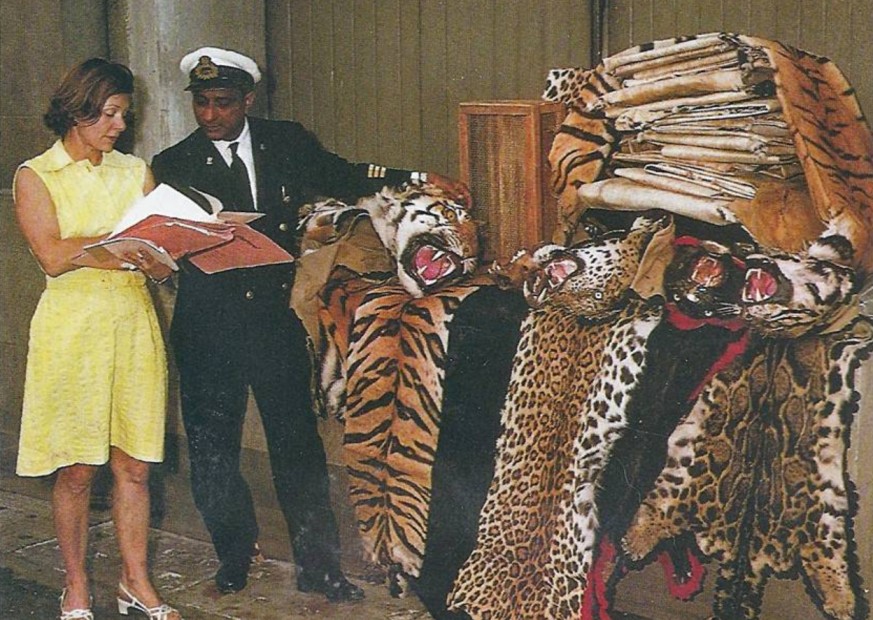

Dasho Benji Dorji, cousin and advisor to the former king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, remembers how she encouraged him in the 1980s to save the habitat of rare black-necked cranes in the remote Bhutanese valley of Phobjikha that was threatened by plans to grow seed potatoes commercially. In Calcutta, says Dorji, he saw how “traders in wild-life parts were terrified of her – she used to take the police and get them all arrested”.

Anne Layard was born in Hampshire on June 10, 1929 into a privileged British colonial family who had served in India and Ceylon for two centuries. They also included Sir Henry Layard who discovered Nineveh in what is now Iraq. Her father retired as Chief Secretary of the Central Provinces in 1947 and took on an advisory role as counsellor in the new UK High Commission in Delhi. That led her to a friendship with Pamela, Mountbatten’s daughter, one of many such illustrious connections – Mountbatten was in his final year in India.

Her early married life was spent in the social whirl of Calcutta, with her husband Bob who died in 2005. From their home in Calcutta’s prosperous area of Ballygunge, they became the centre of the energetic social life that the already dwindling British expatriate crowd continued through the 1950s and 1960s, India’s political capital had moved to Delhi but Calcutta, now Kolkata, remained a boisterous business hub with a social life that drew royalty from neighbouring Bhutan and Nepal as well as maharajas and other dignitaries.

Bob held senior posts in business and was involved in numerous charities, but is best remembered for managing from 1972 to 1996 the city’s famous Tollygunge Club and acting as the UK’s unofficial but influential consul in West Bengal.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.