At Vantara, Modi Posed With A Blue Macaw. Here's Why It is a Red Flag

Bengaluru: On March 3 this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Vantara, officially known as the Greens Zoological Rescue and Rehabilitation Center (GZRRC), at Jamnagar, Gujarat. One of the many animals that Modi posed with at Vantara in elaborate photo shoots was the Spix’s macaw, also known as the blue macaw – a stunning parrot from Brazil that sports many-hued blues. The bird, found only in a small area in northeastern Brazil, is now extinct from the wild. Except for around 11 birds that were reintroduced into the wild in 2022, all existing individuals are in captivity, in zoos and breeding centres across the world.

Modi’s photo with the blue macaw caused quite a flutter. As per a news report published by a Brazilian media house on April 9, the Brazilian government – which requires that all blue macaws that cannot be looked after be sent back to Brazil for its Spix macaw reintroduction programme – was unaware of the transfer of the birds to India. The report also suggests that Vantara may have paid money to a breeding centre in Germany for the birds. The breeding centre has, however, denied this, according to the report.

As The Wire reported on March 21, Brazil has repeatedly raised the issue of Spix’s macaws being transferred without its endorsement to Vantara from the breeding center in Germany, at both the 77th and 78th Standing Committee meetings of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in November 2023 and February 2025 respectively.

Also read: Congo Chimps at India’s Vantara: A Case of Capture From The Wild?

Meanwhile, photos of public figures posing with exotic wildlife on social media come with its dangers. Research shows that this can escalate the popularity of owning exotic wildlife, and add to the false perception that they make for suitable pets. As a result, this, again, spurs illegal wildlife trade, promoting animal collectors to capture animals from the wild to meet demands.

View this post on Instagram

But first, what are blue macaws?

The little blue bird, Spix’s macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii), is a parrot endemic to northeastern Brazil. Here, it dwelled in a small area of a very unique ecosystem called the ‘caatinga’, a dry forest consisting of shrubs and woodlands. However, then came trouble: this shrub-woodland habitat with specific plants and fruits that the macaws needed to survive on began to disappear as people cleared these areas to cultivate crops and establish ranches. And the bird’s rarity, along with its charming blue plumage made it highly sought-after by collectors. According to studies, the first records of the bird being captured for the pet trade – to be kept as a cage-bird – date back to the early 1900s. Collection worsened between the 1960s and 80s, and by the time people even tried to map its distribution in the area, the species was down to the last three birds in the wild in 1986.

Surveys show that the species has vanished from the caatinga since then. Since 2019, the IUCN Red List has categorised the Spix’s macaw as “Extinct in the Wild”. The last remaining birds – about 360 of them – are all in captivity in zoos or breeding centres. In 2022, Brazil released around 20 captive-bred Spix’s macaws in the wild. Now, 11 remain in the caatinga.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) – which bans trade in endangered species across the world – lists the Spix’s macaw in Appendix I. It is illegal to trade in species listed in this appendix unless under very rare circumstances, such as for scientific research.

The Brazilian government requires that all blue macaws that cannot be looked after in breeding centres or zoos be sent back to Brazil for its ongoing breeding and reintroduction program. Every bird is precious for the program, as the only hope of reintroducing the species back into the wild now is through ex-situ breeding, or breeding the birds in breeding centres, and then releasing them in the wild.

The German connection

The biggest captive flock of Spix’s macaws is at the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP) in Berlin, Germany, founded by Martin Guth (whom The Guardian calls a “former nightclub manager and unofficial debt collector”). Mongabay reported that in 2020, the ACTP sent 52 birds back to their home country for the reintroduction program as part of an agreement with the Brazilian government. The agreement, between the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), the Brazilian government agency that manages protected areas and biodiversity in the country was active for five years – from 2019 to 2024.

In late January this year, media houses ran glowing accounts of how Vantara – founded in 2019 by Anant Ambani, son of billionaire Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries fame – partnered with the ACTP to transfer 41 Spix’s macaws from Germany to Brazil. Thanking Anant Ambani, Guth said:

“In addition to their generous financial support, the expertise that Vantara shared with us has been invaluable in successfully breeding this extinct-in-the-wild species…This partnership exemplifies the power of a shared vision and commitment, and we hope it will inspire conservation efforts worldwide. We look forward to continuing our work together to save as many endangered species as possible in partnership with Vantara.”

But there’s more to this “major milestone” – as the papers called it – than meets the eye.

‘Send back our macaws’

In its annual report for 2022-23, Vantara said that it had begun conservation breeding programmes for several endangered species, including the Spix’s macaw. On February 7, 2023, the facility acquired 26 Spix’s macaws – 12 males and 14 females – from the ACTP.

“The birds are currently housed in the state-of-the-art breeding facility at GZRRC that was specially designed to meet their species-typical requirement. These birds will be part of the global breeding programme for these species. GZRRC is one of the very few facilities in this world that has the necessary expertise and infrastructure to maintain a captive population of these birds for the purpose of ex-situ conservation. The captive population of these species at GZRRC shall act as an insurance population of the species. It is hoped that the captive breeding of these species at GZRRC could provide individuals which can then be released into the wild,” the annual report read.

Also read: South African Animal Rights Group Calls for Probe Into Ambani-Owned Vantara

On March 3 this year, Modi visited the GZRRC, or Vantara, and posed with several animals from the facility. One of them was a Spix’s macaw.

This photo graced a news report by Brazilian media house Conexão Planeta on April 9. The report said that the Brazilian government was unaware of the transfer of the birds to India from the ACTP in Germany. Conexão Planeta said that it had obtained exclusive information that an ex-situ reproduction centre of the blue macaw was being created in the conservation centre of India, and that the Landesamt für Umwelt (LfU), Department of Environment of Brandenburg – the German state where the ACTP headquarters is located - had also confirmed this.

Brazilian authorities – both the ICMBio and IBAMA – told Conexão Planeta that they were aware of this, but were “totally against the decision”.

The Conexão Planeta report also said that while the ACTP denied that there was payment made by Vantara for the transfer of the blue macaws, documents that were part of the agenda of the CITES meeting in 2023 showed that Brazil mentioned that “significant values” were involved in the transaction between the ACTP and Vantara. The report also noted that Guth – founder of the ACTP – may be possibly involved in bird trafficking, and that there is “lack of transparency in relation to how financial resources are obtained”.

The Conexão Planeta report quoted Dener Giovanini, general coordinator of Brazil’s National Network to Combat Wildlife Trafficking, as saying that the entire process of the transfer of blue as well as Lear’s macaws (another parrot endemic to Brazil) was “scandalous”.

“Every day it becomes clearer that we are facing a history filled with corruption and connivance of authorities with the international trafficking of threatened species of the Brazilian fauna…The Brazilian government made a mistake in allying itself with animal traffickers disguised as conservationists,” Conexão Planeta quoted him as saying.

The GZRRC, meanwhile, has maintained that allegations that it may be furthering illegal wildlife trade through its “rescue” operations is “entirely baseless” and “misleading”.

In March this year, the GZRRC told The Wire that it “does not create demand for wild capture” but that they exist to “rehabilitate animals that have already been displaced, kept in captivity under inadequate conditions, abandoned, or confiscated by enforcement agencies”.

“To suggest that our work fosters illegal wildlife trade is a gross misrepresentation,” the GZRRC had told The Wire.

CITES documents add proof

Documents in the public domain that detail the stand of various countries at CITES meetings also establish that Brazil did not endorse the transfer of Spix’s macaws to Vantara in India from the ACTP in Germany. Brazil has been reiterating that all remaining Spix’s macaws be sent back to their home country if they cannot be looked after. A report on the live trade of Spix’s macaws that Brazil submitted to the 77th CITES Standing Committee meeting at Geneva, Switzerland, in November 2023 reads:

“Any transfer of Spix’s macaw currently in the possession of international breeders must be sent primarily to institutions located in Brazil, the country of their origin and from where the species was illegally removed, in the past. In the same way, any need to fragment the population for “risk diversification” should prioritize sending it to institutions in Brazil, which are fully capable of implementing the management program of the species, with the ultimate objective of achieving its sustainable reintroduction to wildlife.”

As The Wire reported on March 21, CITES documents reveal that Brazil has been repeatedly bringing up the issue of the unauthorised transfer of Spix’s macaws from the ACTP in Germany to Vantara in India, at the last two CITES Standing Committee meetings. Brazil has also stood firm that neither the ACTP nor Vantara are linked to its Spix’s Macaw Population Management Programme in any way.

At the 77th meeting of the Standing Committee of the CITES in November 2023, Brazil noted “specific concerns” about the transfer of the macaws to India and pointed out that it had, in a notification to CITES members in 2001, requested that no country issue import, export or re-export permits for the species without consulting with the Brazilian CITES Management Authority. Germany, however, claimed that it was not aware of the notification at the time of the export and said that it would follow this in future.

At the next Standing Committee meeting in February at Geneva this year, Brazil once again raised the issue of Spix’s macaws being re-exported without its endorsement. The CITES Standing Committee requested all countries that have captive Spix’s macaws – including India – to engage with Brazil on this. Brazil underlined how important each individual of the Spix’s macaw was for its reintroduction program. The Standing Committee then invited Brazil, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, India, Switzerland and other countries that have Spix’s macaws in captivity in their territories, “to engage in a dialogue to enhance exchange of information” to support the Spix’s Macaw Population Management Programme, and report back on this to the Standing Committee at its next meeting which will be most likely be next year.

It was at the same meeting – the 78th Standing Committee meeting of CITES – in February this year that Vantara said that it had partnered with the ACTP since 2023 to support the reintroduction of the Spix’s macaw to Brazil. The ACTP said that along with Vantara, 41 Spix’s macaws had been “successfully transferred to Brazil” and would be prepared for release. However, Brazil held that the ACTP, or any Indian facility, was not part of the Spix’s Macaw Population Management Programme.

In November 2023, though the ACTP issued a public statement claiming that the partnership with GZRRC, or Vantara, was communicated to the Brazilian government on November 7, 2022, and was duly recognised, Brazil “disputes” this claim, the CITES documents said.

“For an institution to join the Management Programme, it is necessary to submit specific forms … and sign a term of adhesion. None of these procedures were followed for the GZRRC,” the documents read.

The documents also said that in April last year, Germany told Brazil via email that the ACTP had applied to transfer 70 Spix’s macaws out of Germany – 41 to Brazil, for the reintroduction program, and 29 to Vantara. However, the CITES management authority in Brazil – the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) did not endorse the transfer to Vantara as it was not part of the Spix’s Macaw Population Management Programme.

Astonishingly, on May 6, 2024, the ACTP filed yet another application seeking to export 101 birds in total: 41 to Brazil, and 60 to Vantara. Once again, Brazil did not authorise this transfer to the Indian facility.

Posing with exotic pets: A dangerous trend

Amidst all this is another growing concern: the problem of posing with exotic pets. Free-handling exotic wildlife, posing with them and putting visuals or videos on platforms that are accessible to the public – such as on social media, like Prime Minister Modi did at Vantara – has a dark side. Some say that videos of people interacting closely with exotic wildlife garner positive attention, in terms of awareness about the species. But more often than not, viewers have no idea about the conservation status of a species – about how threatened they may be – and visuals of humans handling exotic pets make prospective buyers/collectors covet them even more.

Research suggests that videos and photos of wild animals in social media tend to influence public perception about ‘cute’ exotic animals: they make exotic pets more desirable, and thus promote more demand.

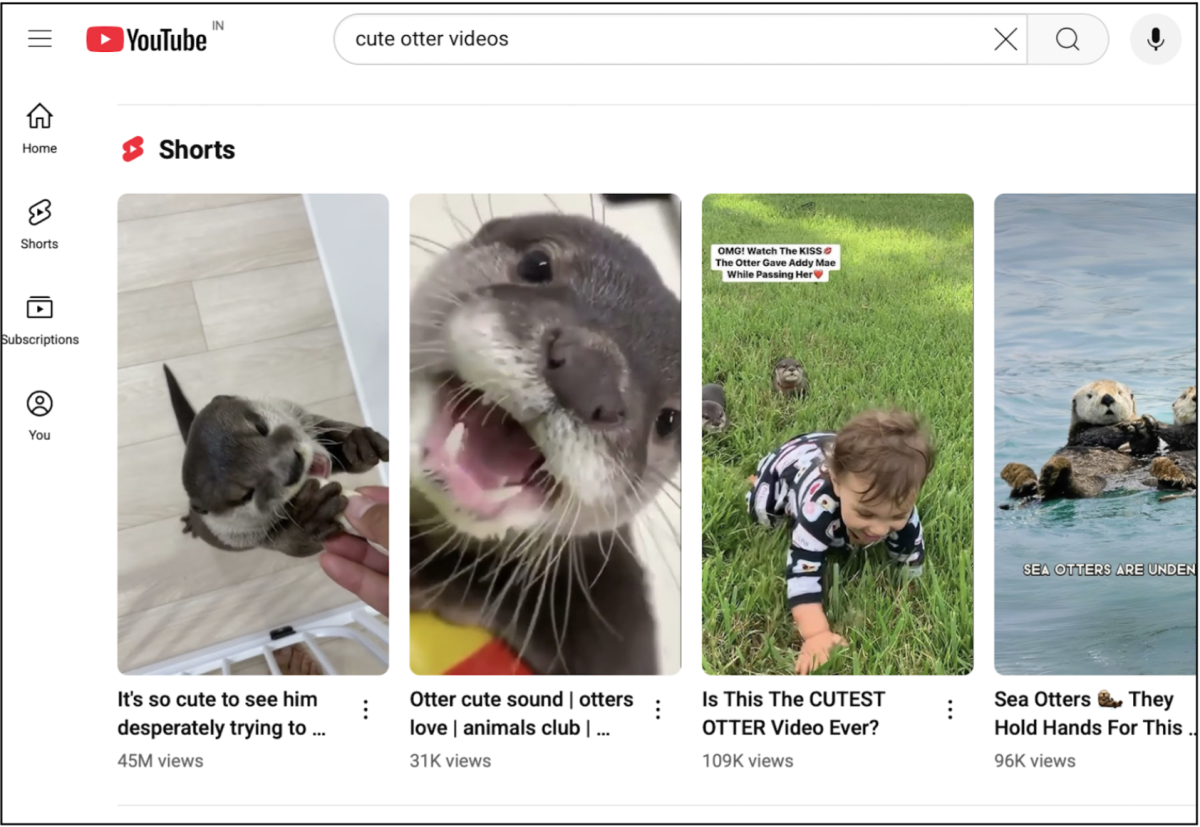

Results of a YouTube search for “cute otter videos”. The videos show people interacting with small-clawed otters, and their views run in millions. Source: YouTube

Take this example of otters on social media, for instance.

A simple YouTube search for “cute otter videos” shows people interacting with small-clawed otters, feeding them and keeping them as pets. Video views run in millions. Incidentally, the IUCN Red List categorizes small-clawed otters (Aonyx cinerea) as “Vulnerable” due to decreasing populations worldwide. In India too, the species is afforded the highest legal protection under Schedule I of the Wild Life Protection Act (1972) - protection on par with a tiger - which also makes it illegal to keep the species as pets. Apart from the more apparent threats of habitat loss due to human activities and being poached for its fur, experts list the illegal pet trade as a huge, emerging concern for the species across its range in southeast Asia.

A study in 2019 found that between 2016 and 2018 alone, the number of videos depicting pet otters on YouTube increased, as did their popularity and engagement. People commented on these videos with phrases such as “I want one”.

“Our results show an increase in social media activity that may not only be driving the apparent increase in popularity, but also amplifying awareness of the availability of these animals as pets, as well as creating and perpetuating the (erroneous) perception of otters as a suitable companion animal,” the study noted.

A lot of the illegal pet trade has also moved online. Studies such as this one in 2018 suggest that the sheer numbers of otter pups on social media that are available for sale suggest that they are captured from the wild to meet the huge demand for the species as pets.

This article went live on April seventeenth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-six minutes past five in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.