How Difficult is it to Breathe in Gaza?

This June, a flotilla headed to Palestine to symbolically break Israel’s blockade of food and other aid to Gaza. Now, another fleet of flotillas is trying to do the same. Common to both efforts is Greta Thunberg, who for many is the face of the movement against climate change.

Thunberg's presence in the flotilla drove home a point that many had not considered amidst the headlines on Israel’s genocide at Gaza – that the destruction of humans, their homes and surroundings, at scale, was a climate problem. A section of commentators, already critical of Thunberg’s stance against genocide, wondered why she wasn’t focusing on her main thing – climate change.

But here’s the maddening fact – climate change harms life. And war also harms life – perhaps degrees quicker than climate change. Any movement for climate justice is, at its most fundamental level, an embrace of the value of healthy life and thus anti-war in its very essence.

Colonialism, kinetic war and a ritual disavowal of the value of life are grave environment threats which worsen the climate emergency we confront. That Gaza, the livestreamed genocide of our times, is testament to this is obvious. From October 2023 till now, over 65,000 people were killed as a result of Israel's military campaign in Gaza, according to Palestine’s health ministry. Recent research complements what is wildly apparent from footage of Gaza – that injured and displaced survivors are not given a world in which they could be doing any better. They cannot even breathe safely.

Smoke and flames rise from an Israeli military strike on a building in Gaza City, Friday, Sept. 12, 2025. Photo: AP/PTI.

What five pollutants say about an ‘ecological crisis’

An assessment by geographer Ammar Abulibdeh of the Qatar University and published in the journal Global Environmental Change, combines Sentinel-5P satellite observations with statistical and machine-learning techniques to find the environmental impacts of the war in Gaza. The Sentinel 5P satellite is a space mission dedicated to monitoring the Earth's atmosphere. It has also been useful in measuring the extent of environmental damage in Ukraine, as a result of Russia’s war.

The paper finds that the onslaught in Gaza results in severe environmental degradation, primarily through the release of hazardous air pollutants and the widespread destruction of infrastructure. Military operations have contributed to elevated emissions of different gases, including NO2, SO2, CO, CH4, and aerosols, among others, originating from missile strikes, fuel combustion, and fires, the paper says.

These pollutants not only degrade air quality but also initiate complex chemical reactions that lead to the formation of secondary pollutants, such as particulate matter, the paper says. Additionally, the destruction of buildings and industrial facilities cause the release of toxic substances, posing long-term risks to both ecological and public health. The environmental toll is further compounded by the collapse of waste management and sanitation infrastructure – something Gaza environment activists have been drawing attention to – and which accelerates the release of methane and other harmful gases, the paper notes.

Together, these consequences affect the atmospheric and ecological stability of a region where not even journalists are allowed, let alone researchers. Abulibdeh’s study combines remote sensing and predictive modelling to address this lack of ground-based data as it studies the levels of five key atmospheric pollutants – UVAI, CO, NO2, SO2, and CH4 – over a multi-year period.

| So, what are these pollutants? The UVAI or Ultraviolet Aerosol Index is a key metric used to identify the presence and strength of aerosols like dust, smoke, and volcanic ash. NO2 or nitrogen dioxide is released upon combustion of fossil fuels. It is also toxic. CH4 or methane is a greenhouse gas that is believed to quicken climate change. |

“The findings highlight that conflict is not only a humanitarian and political crisis but also an ecological one,” Abulibdeh notes in his paper.

‘Every aspect of the environment destroyed’

His is not the only effort that attempts to make the grave case for the depth of environmental degradation in Gaza, and not just since October 2023.

"Gaza has seen recurring periods of damage during active hostilities, the environmental impact of these has been exacerbated by the Israeli blockade and occupation that have impaired efforts towards environmental recovery, as well as reducing opportunities for sustainably managing resources like water. What we have seen since October 7 is of a far greater magnitude, and the deliberate destruction of the Strip and its life support systems, such as agricultural resources,” Doug Weir, research and policy director of the Conflict and Environment Observatory, tells The Wire.

To a bystander, this war has made mockery of efforts at sustainability and maintaining a green culture, spiking carbon emissions, fast-tracking ecological degradation and ensuring that the conditions in which survivors get to live in are hazardous at best.

In the early days of escalated conflict, in 2023, Human Rights Watch had flagged Israel’s use of white phosphorus – a grave threat to human health that is difficult to extinguish once ignited.

A 2024 study noted that in the initial two months following October 7, 2023, the conflict’s emissions equaled the burning of at least 150,000 tonnes of coal, producing more greenhouse gases than the annual carbon footprint of many climate-vulnerable nations.

Another 2024 study estimated that carbon emissions arising from post-conflict efforts in transporting building debris to nearby disposal sites, and from crushing uncontaminated concrete rubble into finer aggregates for reuse in building blocks, roadway repair, and shoreline protection could generate around 55,513.95 tonnes of CO2e.

Since 2023, the words of Nada Majdalani, the Palestine director for the group EcoPeace Middle East, to Al Jazeera have been quoted multiple times. Majdalani has famously said, “On the ground, this war has destroyed every aspect of Gaza’s environment.”

Smoke rises following an Israeli military strike in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, Friday, September 26, 2025. Photo: AP/PTI

As early as last year, researchers were calling the extent of environmental damage a war crime by itself, and using the term ‘deliberate ecocide’ to describe the destruction to Gaza’s ecosystem. A 2024 analysis of satellite imagery provided to The Guardian in Britain showed that about 38-48% of tree cover and farmland had been destroyed.

A UNEP assessment last year noted the severe health risks this environmental degradation posed to Gazans.

A report by the Turkey-based Anadolu Ajansı in September 2024, quoted Yara Asi, an assistant professor at the University of Central Florida’s School of Global Health Management and Informatics as having said, “This isn’t a population that is smoking. This is a population that is living amid ruins ... with dust, smoke and toxic chemicals that they cannot avoid.”

Experts quoted in this report point to long-term health consequences of breathing in air polluted to this extent thanks to the incessant bombing and destruction afoot. Footage that reaches us through social media shows humans cloaked in dust, and the air yellow with all-encompassing soot.

Space, time and pollutants

Abulibdeh’s study drives home the fact that military strikes in urban centres like the densely populated Gaza city not only destroy infrastructure but also generate substantial airborne emissions, revealing significant shifts in pollutant levels during the war period.

The study notes distinct spikes in pollutants, such as SO2 and UVAI, after October 2023 – something that reflects the environmental cost of military activities, including but not limited to infrastructure destruction.

In a land affected by famine, these pollutants pose severe public health risks, especially in densely populated urban areas already burdened by constrained healthcare systems. Note that Gaza is only an area of 365 square kilometres.

One of the most notable patterns the study observes was the prolonged elevation of UVAI throughout 2024, even outside traditional high-aerosol seasons. This indicates that anthropogenic emissions, including smoke, dust, and construction debris have disrupted natural environmental rhythms, it finds.

The recovery from the “environmental shocks” in Gaza will be felt much after the attacks end, the study reveals, citing the persistence of elevated aerosol levels.

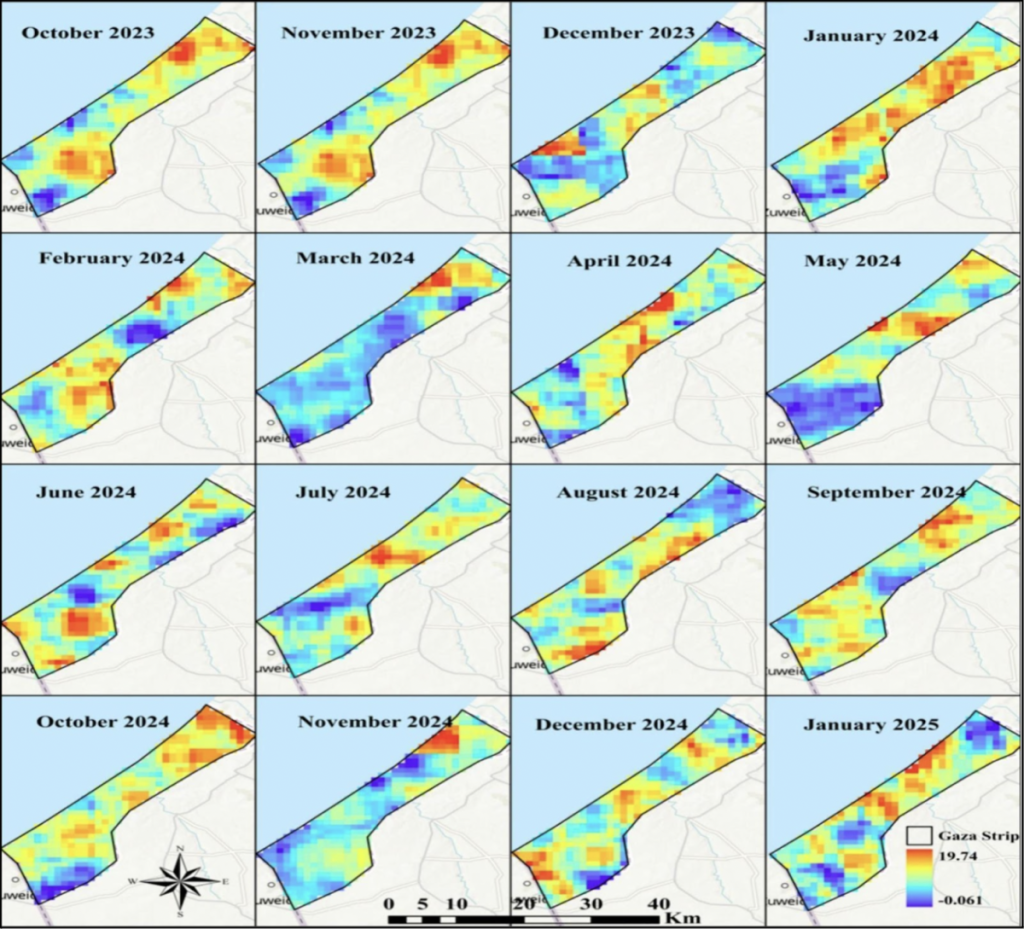

Visualisations in Abulibdeh’s paper provides critical insights into how pollution levels have shifted particularly during periods of intensified conflict.

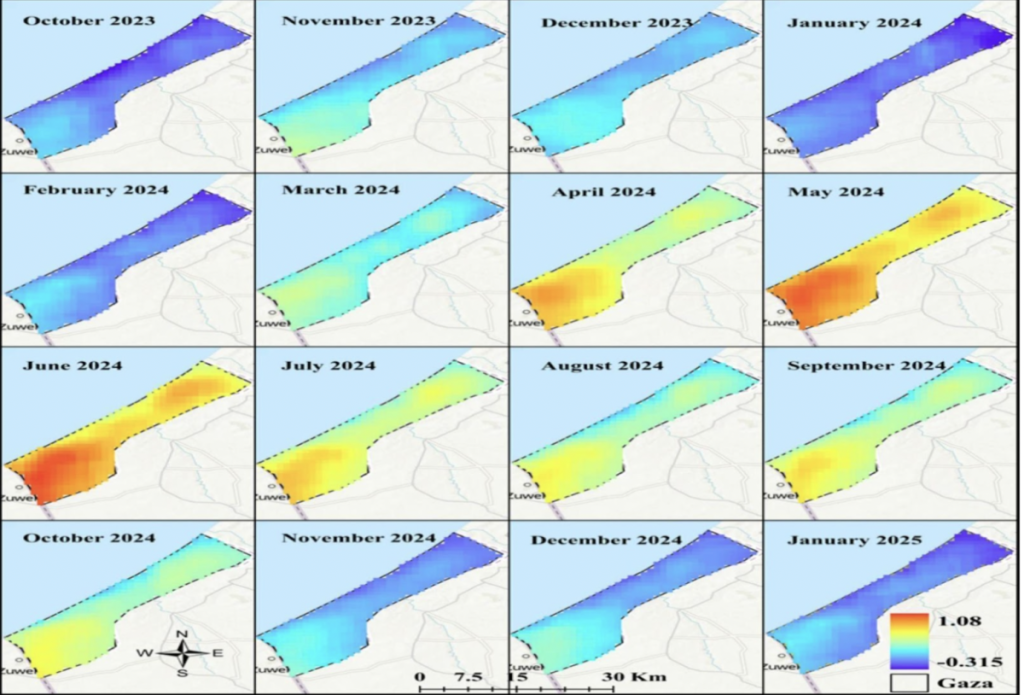

Above: Spatial distribution of UVAI in Gaza across time.

The UVAI shows a dramatic and prolonged increase starting in 2022, remaining elevated in 2023, with cumulative values peaking in 2024. Spatially, while low UVAI levels were observed in the early war months, beginning in March 2024, hotspots emerged in Gaza City and intensified in southern cities, such as Khan Younis and Rafah. The study notes that these are the areas that experienced extensive bombardments, building collapses, and the combustion of materials, all of which contributed to elevated levels of UV-absorbing aerosols – pointing to seriously deteriorating air quality.

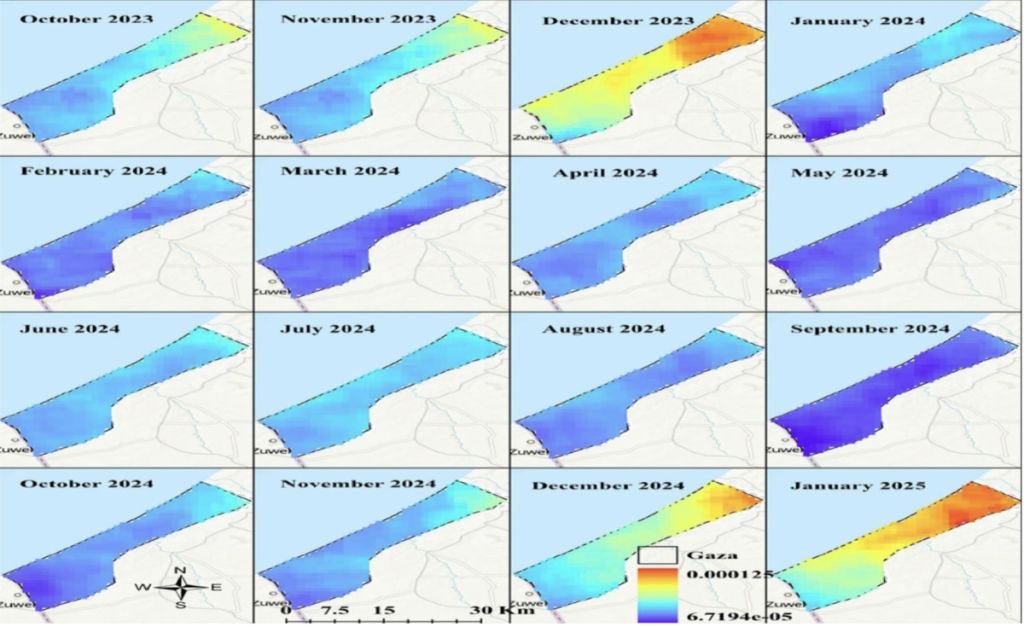

Above: Spatial distribution of NO2 across time in Gaza.

The study of NO2 patterns is interesting because after a temporary increase in December 2023, in what the paper assumes is due to military vehicle movement and emergency responses, NO2 levels dropped sharply and remained low throughout 2024. This is not necessarily reason to rejoice, because it could point to the collapse of transportation, industrial activities, and fuel supply chains – reflecting the contrasts in even the narrowest studies of the environment and the difficulties associated with quick conclusions. The study did, however, note a mild resurgence in December 2024 and January 2025 over Gaza City and Deir al-Balah, perhaps in a suggestion of a tentative reactivation of urban life and recovery activities.

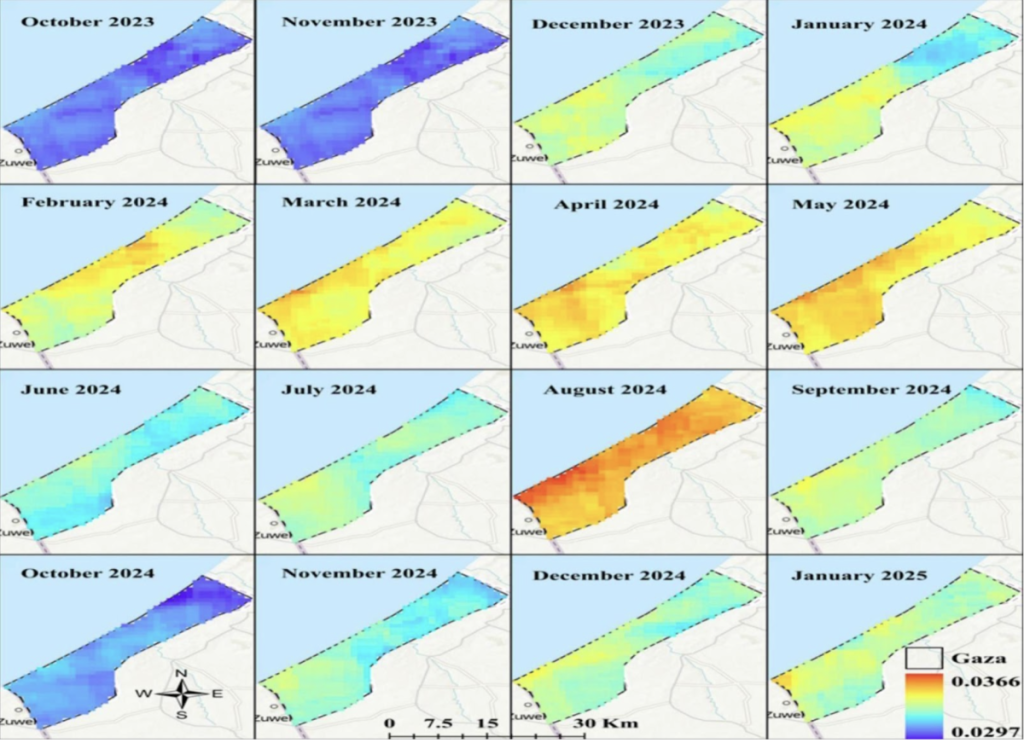

Above: Spatial distribution of CO across time in Gaza.

CO concentrations, meanwhile, rose steadily through the conflict, spiking sharply in central and southern Gaza starting January 2024. Densely populated Gaza City, Khan Younis, and Rafah “exhibited the highest CO concentrations.”

These trends align with the widespread use of backup generators, open burning, and fuel combustion in makeshift shelters during the war, the study says.

As early as 2021, The Conflict and Environment Observatory had studied an 11-day conflict in Gaza in that year. It had made a pertinent and prescient note about the choice of places which were harmed the most: “Where, when and how civilians have been harmed tells an important story about how choices made by belligerents can and do continue to have devastating impacts upon civilian lives – and clearly demonstrate why the use of explosive weapons with wide area effects in populated areas must be stopped."

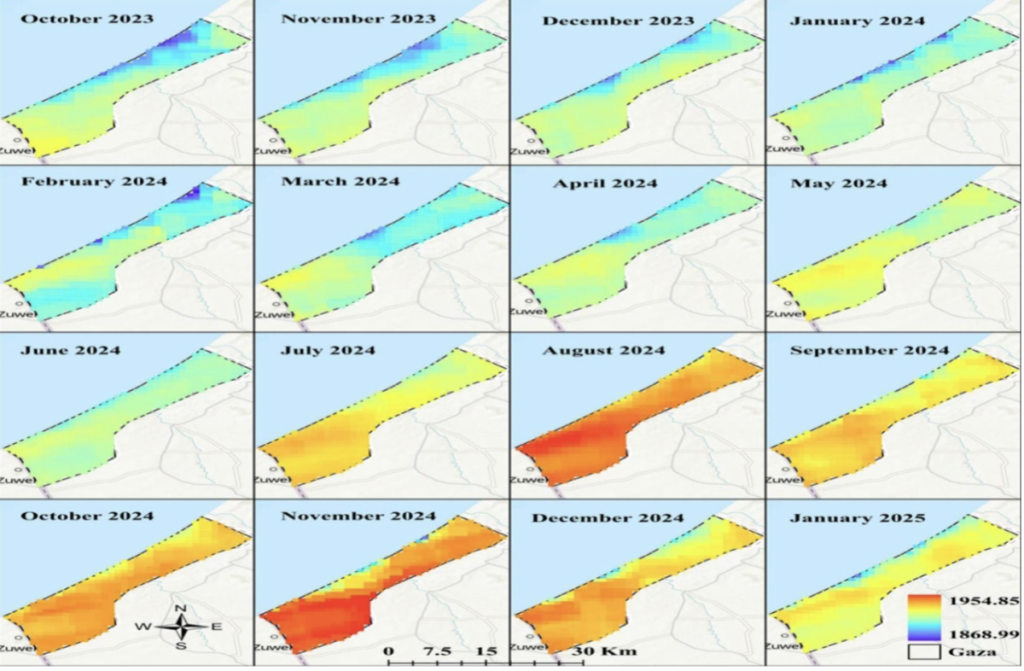

Above: Spatial distribution of CH4 across time in Gaza.

The study finds that among all pollutants, those that originate from organic decomposition and waste processes showed the most sustained and pronounced cumulative increase – and thus after a brief decline in 2020, CH4 concentrations rose sharply and continuously through 2024. “This persistent growth indicates ongoing emissions from deteriorating waste management systems, leaking sewage infrastructure, and decomposing materials, issues that are exacerbated during prolonged conflict,” the study notes, saying that the war exacerbated these conditions by disrupting public services and displacing populations, which in turn intensified emissions.

Almost a year ago, the UNDP’s Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian people had recorded that there is no access to the major landfills, and waste accumulates at more than 140 temporary dumping sites which causes serious health and environmental risks, including a spike in diarrhoea illness and in acute respiratory infections.

Spatial distribution of SO2 across time in Gaza.

SO2, which is most commonly associated with fuel combustion and the destruction of industrial facilities, showed elevated levels in Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah at the start of the 2023 conflict. A temporary decline followed, but by mid-2024, concentrations rose sharply again, particularly in southern Gaza.

While they declined in October, areas such as Rafah continued to exhibit elevated levels into January 2025, in what the study finds is a phenomenon underscoring the lasting environmental impact of conflict in southern cities.

The study maps a direct and damning correlation between military activity and air quality in a phenomenon that affects the most number of people where they are likely to have gathered in the largest numbers. “Regions like Khan Younis and Rafah exhibited more severe environmental burdens,” it notes.

Smoke rises from an Israeli army bombardment in Khan Younis, central Gaza Strip, Thursday, September 11, 2025. Photo: AP/PTI

The importance of studies as this one is highlighted by the astounding reality that the world's militaries account for up to 5.5 % of total global greenhouse emissions, yet there is still no requirement for governments to report these emissions in international climate agreements. Researchers are largely left on their own to gather data on and assess military emissions.

The Conflict and Environment Observatory in its ‘Military Emissions Gap’ database records that Israel does not report military emissions data under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change guideline 1A5. This, despite the fact that Israel’s defence expenditure vis-a-vis its Gross Domestic Product, puts it near the top of global militarisation indices.

"Many militaries remain reluctant to disclose their full emissions, although many of these have not had the systems in place to effectively track them, this is slowly changing but the picture remains far from complete. Because the reporting of military emissions is voluntary under the UNFCCC, there has been less pressure on states to address this. A longstanding tendency towards environmental exceptionalism for militaries has also contributed,” says CEOBS director Weir.

Amidst this significant gap in offering data, this study notes that traditional models based on peacetime data do not serve the spatially compact Gaza Strip, where sea winds lead to pollutants shifting rapidly between zones. It calls for the development of conflict-sensitive models that integrate geospatial dynamics, infrastructure damage data, and population movement patterns to more accurately estimate real-time environmental risks.

"Several years ago Gaza was predicted to be an "unliveable" place by the 2020s because of the environmental consequences of years of occupation. The appalling degree of damage now wrought by Israel has impacted air, water and soils in ways that will be felt for decades,” Weir says.

This article went live on September twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty five, at ten minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.