This February has been phenomenal for the atomic energy sector. On February 1, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman indicated plans to open up the nuclear energy sector to market competition. The government aims to amend Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA), 2010 and Atomic Energy Act, 1962 in terms that allow “for an active partnership with the private sector”. Private sector suppliers of nuclear equipment, especially foreign investors, have criticised India’s CLNDA as section 17(b) holds the suppliers – and not just the operators of nuclear installations – liable to provide compensation in case of nuclear accidents.

Following the finance minister’s announcement, on February 18, private multinational conglomerate Adani Group’s chairman Gautam Adani with other officials visited the Tarapur Maharashtra site to sharpen their interest in nuclear power technologies. India is to also start a Nuclear Energy Mission with Rs 20,000 crore investment in research to set up five small and modular reactors by 2033. Additionally, since 2019, the public sector undertaking Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) has had plans to commission ten nuclear power plants “on fleet mode” in Karnataka (two), Haryana (two), Madhya Pradesh (two) and Rajasthan (four).

The Union government has framed these transformations in the nuclear energy sector as efforts to address climate change. As another significant nuclear development in February, but dissentious, on the second, residents around the Kappatralla reserved forest and the Human Rights Forum demanded Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu’s government to pass a resolution against uranium exploration, fearing radioactive contamination of the region. The protest reminds that efforts at addressing climate change must go beyond band-aid technocratic intervention like outlined above. It requires robust environmental law and governance mechanisms where technoscience is, instead, used to address pollution control.

Sure, one could argue that the National Green Tribunal (NGT), a dedicated court to address environmental protection, is an internationally unparalleled institution in place for environmental protection. The readers may question this article for sending false alarms, as scientifically defunct, question the author’s expertise etc. But the manner in which the NGT addressed the Tummalapalle uranium contamination controversy points to the problem in India’s nuclear energy environmental regulation:

(i) On radiation matters, nobody’s opinion expect those of the Department of Atomic Energy or nuclear experts matters;

(ii) that pollution control board has culturally little power to regulate nuclear environmental controversies;

(iii) any effort by civil society to surface radioactive contamination is marked seditious and against national developmental interest.

In such a scenario, the questions that reverberate in the depths of Tummalapalle’s irradiated mine shafts are “whose expertise one is to rely on?” “whose voice/opinion count?” “whose knowledge matters?” in adjudicating the controversy, and protecting those who have been harmed.

So what happened at Tummalapalle?

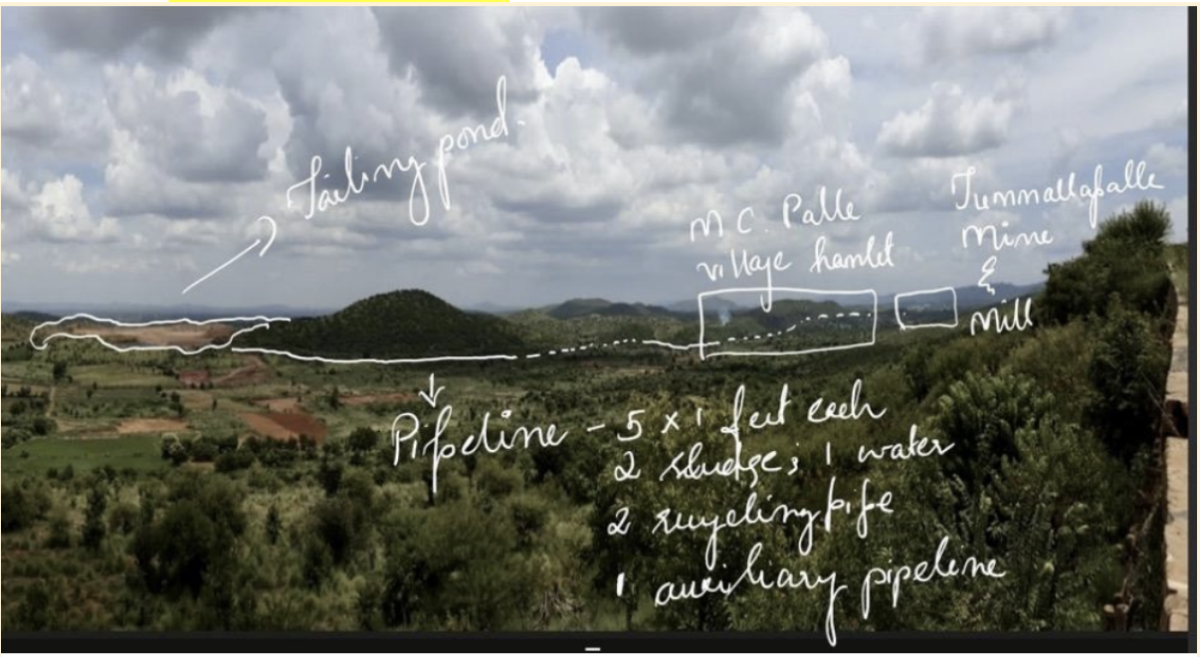

Between 2016 and 2018, farmers at Tummalapalle started noticing that their crops were showing stunted growth, falling short of expected yield, and faced enormous loss. These farmers were from MC Palle and Kottala villages located within the two-three kilometre periphery of the tailing pond (100 hectares in size) of the Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill.

Panoramic view of Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill. Source: Misria Shaik Ali

Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill (TUMM) was set up by Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL), a public sector undertaking of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) in 2012. The Mill is almost four kms away from the tailing pond where the extracted uranium ore is processed into yellow cake. After processing, the waste from the Mill or the tailings, are deposited in a pond called the tailing pond, through a system of five pipelines. The tailings are radioactive and consist of 19 chemicals including six-eight uranium parts per billion (ppb).

In 2018, one of the farmers noticed that the water in his agricultural borewell that runs deep into the underground, has turned white. Once he shared his issues around crop growth with other farmers in a similar situation, eight farmers sent borewell water samples to a centrally recognised laboratory, Central for Materials for Electronic Technology Laboratory for analysis with the help of former panchayat leader, M. Srinath Reddy. The farmers knew that any test in a laboratory not recognised by the Union government would be marked off as false, non-knowledge or worse, motivated by anti-national interests.

Results showed that the water in eight agricultural farmlands and two panchayat borewells ranged from 40.35 ppb to 405.32 ppb of uranium. Whereas, the safe levels for uranium in water is about 60 ppb, according to the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board and 30 ppb, according to WHO.

On request, officials from the Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board (APPCB), the Department of Agriculture and the district magistrate visited the contaminated farms and APPCB, after review, issued a show-cause notice to UCIL on April 2, 2018. In a letter dated April 19, 2018 to UCIL, APPCB noted that uranium contamination in surrounding villages ranged between 690 to 4000 ppb.

Pollution control or nuclear safety?

In the show cause notice, APPCB remarked that the lining of the tailing pond is inadequate which, it claimed, has led to seepage of the tailings, consisting of 19 chemicals, underground. It asked UCIL to “show cause as to why action should not be initiated against your industry for not complying with the conditions stipulated in the EC [Environmental Clearance], CFE [Consent for Establishment] & CFO [Consent for Operation] orders?”

In his first response to APPCB, TUMM general manager, S.R. Pranesh said that the pond “is lined with appropriate clay material with desired thickness attaining stipulated permeability” according to the nuclear industry regulator, Atomic Energy Regulatory Board “(AERB) guidelines”.

APPCB responded that, in its consent for establishing the mine provided to UCIL, clay was only one of the three layers that it had stipulated UCIL to line the tiling pond with. APPCB had mandated UCIL to line the pond with two other geosynthetic materials, namely, polyethylene and bentonite.

In a later letter in August 2019, UCIL further added that since the clay material provided “desired impermeability,” it “was not felt necessary” to line the tailing pond with polyethylene sheets “as an extra-precautionary measure”.

UCIL’s non-compliance with pollution control standards stipulated by pollution authority is rooted in its strong held belief that the nuclear regulatory guidelines provided by the nuclear industry regulator, AERB, are adequate to contain the tailings within the pond.

Furthermore, nuclear standards as enforced by industry regulator AERB are distinct from pollution standards that are enforced by the State Pollution Control Board. There are other standards besides the industry standards to ensure environmental protection and lining the pond with geosynthetic materials is one of them. But UCIL remains confident that nuclear industry safety standards address environmental protection as noticeable in the below incident too.

UCIL stated that it has also constructed ten borewells to monitor any migration of tailings from the pond into the underground, according to “AERB guidelines”.

However, villagers claimed that the borewells dug to monitor migration of tailings from the pond into the underground are not near the villages but in arbitrary locations – the author learnt during her ethnographic research in September and October 2021.

Nuclear authorities atop knowledge hierarchies

In matters of nuclear pollution, nuclear experts and their standards enjoy credibility in the eyes of both the public and governance authorities. Take it when the NGT principal court took suo-motu cognisance of the Tummalapalle contamination issue. Both NGT and pollution control boards are under the same Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. However, the NGT simply refused to pass order on the matter deferring to “opinion of the Department of Atomic Energy and stand of the Uranium Corporation” that was based on scientific studies. Scientist Babu Rao of the Human Rights Forum questions the scientific credibility of these studies.

The resort to nuclear industry regulator, AERB, and nuclear industry promoter, DAE instead of pollution governance, to nuclear standards instead of pollution standards, to nuclear experts instead of pollution experts is a pattern that has and could potentially subject India’s environment, residence and farmlands to irradiation. This pattern is both institutional and cultural.

Institutionally, India’s nuclear regulator AERB is housed under the same department, DAE, which manages public sector undertakings like UCIL and NPCIL. So, the regulator is managed by a department that also manages promoters and manufacturers of atomic energy in the country.

Is ensuring nuclear safety just enough for radiation protection?

Sure, the Nuclear Safety Regulatory Authority (NSRA) Bill, 2011, once enacted, is said to separate the regulator from the department, providing the regulator with statutory rights. But just relying on nuclear safety standards and “ensuring” that nuclear safety (the primary mission of NSRA) is being followed in industry does not mean people and the environment are protected from radioactive hazards. As the Tummalapalle case shows, a sole reliance on AERB nuclear-safety guidelines means that other “extra-precautionary” regulatory guidelines like those of the pollution control board become sidelined.

Furthermore, nuclear authorities also know that nuclear safety is but one “very much simpler” way to ensure “radiation protection” whereby nuclear safety and radiation protection are distinct regulatory regimes in IAEA’s global nuclear regulatory order. Nuclear safety involves maintaining control over sources like containing tailings within the tailing pond while radiation protection involves “protection of people and the environment against radiation risks”. Ensuring safety by lining the tailing pond with clay, while it contributes, may not always lead to protection. When safety plausibly has not contributed to protection, authorities must listen to the accounts of those affected by radiation pollution.

Culturally, nuclear safety, nuclear guidelines and eventually, nuclear expertise enjoy more credibility on matters concerning radioactive and uranium pollution in the environment. Needless to say, the farmers and their knowledge of how water flows underground was not even sought by the NGT. In fact, during field interviews by this author it was revealed that none of the villagers know that the contamination of their village, residence and land was adjudicated in the NGT. Their knowledge simply does not count on a matter that endangers their life and livelihood.

Based on a door-to-door survey that the author conducted in MC Palle, there were about 15 pregnancies recorded between January and July 2021 of which seven were terminated between January and July 2021. Barring one case (at sixth month of pregnancy), all others abortions were spontaneous abortions within 20 weeks of pregnancy. Which means around 44% of pregnancies ended due to spontaneous abortion as against an international norm of 30%. In a focus group conducted in October 2o21, the author learnt that every second or third family, mostly in the SC colony, faced reproductive health issues like infertility, irregular menstruation that lasts up to 20 days at times, medically advised abortions on the sight of fetal anomalies on sonograms leading to eugenic logic of disability.

Health authorities acknowledge the extant “health problems,” and these problems have pushed families into a state of involuntary childlessness. It is one thing to choose not to conceive and it’s another thing to be forced not to conceive and that too, as the villagers claim, due to nuclear operations. It is also important to note here that, during summer, the tailings dry up and are blown by strong winds onto residential and agricultural plots. To research and study environmental injustice at this degree is not anti-national or anti-nuclear and on the contrary, comes from a deep sense of commitment to the society which the researcher engages with.

Governance divided

Health, pollution, agriculture, underground water and nuclear authorities work in their own siloed realm of expertise and “risk jurisdictions” refusing to jointly address uranium contamination in the region. This portends what Timothy Naele and Kristy Howey call, “divisible governance.” For radiation pollution to be addressed, guidelines by nuclear authorities and pollution authorities need to be layered atop the tailing pond and such forms of “layered governance” between risk jurisdictions are important in environmental controversies.

The complex ways pollution, water, health, industry risks are intertwined in climate change induced extreme events requires forms of layered governance. As the governance structures to protect people from radiation hazards remain divided, whereby nuclear expertise and safety guidelines are culturally upheld in matters concerning radioactive pollution, whether India is prepared to commission indigenous nuclear power plants that would rely on indigenously mined uranium in regions like Tummalapalle is questionable.

Misria Shaik Ali has done her doctoral research on radioactive contamination along India’s nuclear fuel cycle at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, New York.