This is the sixth article in a series about the Earth-system – how our planet has shaped us as human beings, and how we, in turn, have shaped it. Read the series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Anatomically modern humans – people like us – have been living on this planet for some 300 thousand years. Most of that time – over 98% of our time on Earth – all societies were nomadic, subsisting entirely on foraged, wild foods. There were no permanent buildings or roads. Every person lived in a wild landscape. That is, they didn’t live in a world primarily shaped and controlled by human desires, but rather one where humans were only one among many forces – some equal to or more powerful than themselves –all co-creating their environment.

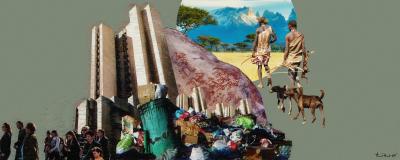

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Popular narratives that imagine those early lifeways tend to presume that our ancestors lived such materially simple lives because they were primitive brutes, simply incapable of building anything more ‘advanced’ or ‘civilised.’ Prehistoric, non-state peoples – often derided as ‘cave men’ – are cast as mentally dim, miserable and hungry, impulsive and cruel in their treatment of each other. Or as Thomas Hobbes imagined it, their lives were ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.’ We expect they understood little and did nothing worthwhile. Since their time, we tell ourselves, humans have followed a preordained path of progress from lower to higher states of understanding and living. We’re led to presume our modern lives are so much richer and full of leisure or pleasure than theirs could possibly have been. And this leads us to presume that those beyond the reach of modernity even today are in want of our ‘civilisation’ and programs for their ‘development.’

But such narratives mythologise both the past and the present in the service of rationalising the status quo, including the present distributions of global power, wealth, and exploitation. These attitudes are the same prejudices once called White Man’s Burden, though we’ve adopted them as our own; we may now say Industrialised Man’s Burden, instead. The truth is, our ancestral cave-dwellers – and the few peoples who live beyond the reach of state power today – simply lived differently and with different expectations than we do. Yet they lived in a state of healthfulness and ease at least as satisfying to them as our own is to us – very likely more so. In modern times, we know that whenever any non-state society has been made to give up their ways of life in exchange for ‘civilisation’ (not to be conflated with individual goods, which they might take and use on their own terms), they have always resisted the imposition with as much force as they could muster; this does not signal desire.

In fact, for most of our human experience, we could neither imagine nor desire any other way to live than to be forever on the move, sleeping in temporary encampments, no other food to eat than what commonly surrounded us. We had no other way to spend our time, other than traveling, adventuring, telling stories, looking after the children, fashioning tools and self-adornments, playing games, singing and dancing, discussing and arguing and sometimes fighting. We continually discovered, tested out, and prepared new foods and medicines, studied the lifecycles of the landscapes and animals and the shapes in the stars. We explored and learned about our world. We searched for meaning.

|

In the wake of British and then Indian colonising encroachments upon the Andaman and Nicobar Islands beginning in 1858, the islands’ ecosystems have become profoundly damaged. Only those areas delineated as reserves for the Adivasis retain their ecological integrity. Despite the obvious value of the knowledge systems that enabled Adivasis to maintain their rich environments for tens of thousands of years, no official efforts are underway to understand or emulate their ecological insights. Rather, the government intends to hasten the destruction of these peoples and their lands in the name of ‘development.’ |

And nor did we need to imagine any other way to live. For the land provided everything we required in adequate abundance, as it ordinarily does for any animal embedded within its ecosystem. Like any other animal, we might occasionally suffer days of hardship or scarcity, but ordinary days – most days – were full and easy. We were healthy, curious, skilled, relaxed, inventive, and regularly lived long, active lives, enough to watch our grandchildren grow up.

In the words of anthropologist Marshal Sahlins, ancient foragers actually lived in the ‘original affluent society,’ for they would have spent little effort to procure everything they wanted and achieved a perfect work-life balance. According to consistent observations of foraging peoples by early anthropologists, missionaries, and European explorers in every part of the world, whatever foragers didn’t have or couldn’t easily make, they didn’t need or generally even desire. They suffered no anxiety over scarcity. They approached the need to regularly move their encampments with the same ease and pleasure that we approach the idea of going out for a stroll. And an individual’s freedom of movement was virtually limitless, underwritten by social networks so broad as to render one rarely without social context or some degree of material support.

More recent studies show that, contrary to popular ideas, after having all their nutritional needs met through their own, non-strenuous labor, foragers still enjoyed far more leisure time than do most of us in the industrial economy. They freely spent their time in self-directed or communitarian pursuits, including sport and play, creative or ritual expression, socializing, or napping. Their social norms actively dismantled material inequities and stopped individuals from claiming disproportionate social power. And every child was raised by a village.

They were securely socially embedded. Finding whatever they needed to make a living was easy, not a cause of anxiety. Plenty of time was spent in pleasurable, creative, political, or other pursuits. Subsistence was entwined with a close, mutualistic relationship to the land. ‘Economic’ exchanges were primarily mediated through the social norms and obligations of their mutual-aid societies, what we call gift economies, rather than through trade or markets. That is the experiential world into which our social psychology evolved, the communitarian reality that deeply shaped what we are as animals.

A painting ‘for the worship of goddess earth and mountain god’ displayed in the tribal museum at Koraput, Odisha. Photo: shunya.net.

Far from being filthy brutes, our ancestors were curious nomads, carefully observing the properties and dynamics of everything around them, ready to discover new paths, places, foods, medicines, materials, relationships, and social structures. And whenever they discovered something new, they added it into their expanding universe of stories. They lived so closely entwined with the wilderness that they understood themselves simply to be part of it, not separate from it – in a manner similar to the worldviews some Adivasi cultures still inhabit today, such as the Dongria Kondh of Odisha.

It matters very much today what we believe about our ancient ancestors. Sociological analyses of historical events have demonstrated that what we believe about ourselves, those around us, and the world we inhabit strongly informs our actions and choices. Erasing our ancient ancestors and Adivasis from the human story, or de-legitimising their ways of being and knowing, which served humanity well for hundreds of thousands of years, is a profound piece of our modern disconnection from reality – not only biophysical reality, but also human social reality.

|

The mythic worlds of many Adivasi groups depict human beings as subject to other living forces of the world. These are not just charming stories, but a way of encapsulating a worldview, a philosophical orientation, a relationship to Earth. For instance, the Dongria Kondh of Odisha well understand and describe their dependence upon the ecological integrity of their land, which they worship as god. This mandates their responsibility to nourish the land and protect it from overexploitation. And it means living with restraint. |

We misapprehend what we are as creatures, if we cannot recognise that the presumptions we make about the world based on today’s conditions are not normal, but actually highly anomalous. Imagining we are somehow different and better – or even better off – than our earliest ancestors is a powerful myth that enables us to presume our modern values and social structures, despite their pathologies, are unequivocally the result of progress, an unalloyed triumph of the human imagination. But our bias for modernity is actually one of the greatest blinders that we have, preventing us from understanding the true nature of our global ecological predicament and what we might be capable of in response to it.

For the most part, our non-agrarian and swidden-farming ancestors knew what they were doing; in terms of living with the Earth, they got a lot of things right. Of course, they also sometimes made misjudgments that led to tragic ends: In their myriad and ongoing experiments with living, through ever-changing conditions, some societies certainly did overshoot the capacity of their local environments, and suffered a commensurate crash. And when people migrated into territories that had never previously known humans, their intrusion contributed to a wave of extinctions that followed their arrival. Without a doubt, communities who suffered such an ecosystem disruption and revision were deeply marked by the experience.

Yet despite all their wandering, their curiosity and experimentation and invention, despite all their errors and failures or even successes, nothing they ever did fundamentally destabilised our planetary systems. This is because our ancient ancestors were neither driven by our modern value systems that promote human thriving apart from the rest of the living world, nor had they overwhelming population sizes to undertake such egregious environmental damage on a global scale. Like us, they were sometimes mean to each other, and corrupt; they sometimes succumbed to their basest impulses for greed, violence, and lust for power – just as we do today. Yet for hundreds of thousands of years, human wellbeing always remained subject to the ungovernable flows of energy and materials through the local ecosystems they inhabited—the same way it was for every other living thing. Never was it the other way around.

This began to change only after the ice age had warmed up nicely into the present interglacial period, the Holocene, some 11,700 years ago. Long before this, most regions of the world were already inhabited by humans. And in this more populous world – while communities did continue to migrate and mix – some populations had remained within the same region for many thousands of years, specialising in particular territories – Amazonia, for instance, the Arctic, Australia, southern Asia, or Africa.

Such communities would have been very familiar with the ecosystems through which they moved during their seasonal cycles of foraging, with local knowledge collected and passed down through their oral traditions across hundreds of generations. They were already enmeshed in broad networks of sociality, cooperation, exchange, competition, and sometimes enmity that spanned halfway across whichever continent they inhabited, encompassing speakers of multiple languages, who nevertheless shared overlapping beliefs, variously expressed through their different cosmologies and stories. Some widespread traditions already involved gatherings of diverse peoples working together to raise architecture for shared purposes, many thousands of years before the rise of cities or states. We see this in the monumental ruins at Göbekli Tepe in Anatolia, for instance, or the great mammoth bone structures found dotting the Russian steppe.

|

Modern ‘development’ schemes seek to change Adivasis’ worldviews. For example, some Kondh peoples have been removed from their ancestral lands, where they once foraged and practiced shifting cultivation, to live now as cash-crop farmers or labourers. They’re being taught to see produce as commodities, rather than gifts of nourishment from their land, to value and seek financial profits, rather than holistic wellness in tune with their land. Their low-demand, low-intensity value systems and lifeways are being eroded, making them dependent upon markets and reducing their ‘original affluence’ to a condition of penury. |

And as the Holocene climate brought more warmth and water to many parts of the world, many peoples enjoyed the enhanced bounty of their increasingly lush environments. In the Levant, the seeds of wheat and barley (jau), two long-known and favored steppe grasses, now grew even more richly than they had during the cold-dry days and became increasingly staple foods. In the Yangtze River Valley of modern-day China, people ate more rice, a local swamp grass. In Central America, they would transform teosinte, a group of tropical grasses endemic to the region, into maize (makka). These nutritionally dense cereal grains had at least three logistical properties in common: 1) relative ease of production into great surplus; 2) annual yields with narrow seasonality; 3) unparalleled storability.

But great food surpluses can lead to population overgrowth and ecological overshoot. A narrow harvesting window makes it easier to control food distribution. And that which can be stored can also be hoarded, stolen, withheld. Together, these properties invited the twin possibilities of material wealth and of poverty – that is, socially-induced scarcity – two conditions previously unknown in human societies. These in turn provided the circumstances for novel forms of coercion, through which some people amassed unprecedented and eventually calamitous social power while others were systematically dispossessed of basic resources and freedoms, giving rise to new social norms imbued with ideologies justifying their inbuilt inequities. And all of this would incentivize economies of plunder and warfare far beyond anything ever seen before.

Thus, in the warm, stable climate of the Holocene, the expanding cultivation of grass seeds would come together with human propensities for seeking power and control, with our fears and insecurities, emerging together in an unexpectedly powerful symbiosis. This profoundly changed us in ways we could not have foreseen – our very experiences of life and Earth and meaning and sense – and through us, it changed the whole world.

With this so-called Agricultural Revolution begins the rift in the human story that makes our prehistoric ancestors seem to us so remote and inscrutable. Yet they were us; we are them. It’s the conditions around us – largely of human making – that have changed, most deeply in the stories we tell. If we keep this in mind, there is something to be learned from those who walked the earth long before us, or even non-industrial peoples today who see the world very differently than most of us.

Usha Alexander trained in science and anthropology. After working for years in Silicon Valley, she now lives in Gurugram. She’s written two novels: The Legend of Virinara and Only the Eyes Are Mine.