This is the eight article in a series about the Earth-system – how our planet has shaped us as human beings, and how we, in turn, have shaped it. Read the series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Much as men were likely the primary hunters in foraging societies across the ages, so women were the primary ‘gatherers’ and plant specialists, providing the bulk of the food and medicine. By 21,000 BCE, those of the Levant knew well the produce of their coastal woodlands and neighbouring steppelands, which stretched eastward for hundreds of kilometres. At least two common steppe grasses, wheat and barley (jau), produced tasty, nutritionally-dense seeds. Using long, thin, flint blades, they gathered these grasses by the armload. In their small encampments, they threshed out short mounds of seeds and ground these with stones.

Alongside more than a hundred varieties of other plants they gathered nearby, plus meat from hunting, this grain provided an astonishing, almost effortless surplus from their cold, arid landscape. Even with the world in the grip of extreme glaciation, it was enough for their small bands to remain stationary for most of the year—the first multi-seasonal camps we know of, anywhere in the world. But eventually the nomads moved on, leaving behind their heavy mortars to be found and reused in future years, if the grasses grew well.

Kebaran mortar and pestle, dating from 22–18 thousand years ago. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem Archaeology. Photo: Gary Todd/Public domain

Such opportunistic trysts with wild grain would take some 15,000 years to develop into the kind of intensive, fixed-field agriculture needed to support a city, and another 4,000 years to take over the world. Indeed, this ‘Agricultural Revolution,’ regularly presented as a grand origin myth of modern civilisation, was neither a swift nor serendipitous innovation eagerly embraced by all. Nor would it herald a giant leap in the social, healthful, and creative prospects of humanity.

By 9000 BCE, in the significantly warmer, wetter conditions of the early Holocene, lush grasslands shimmered from the expanding Levantine woodlands toward the eastern horizon. Foragers living there and in southern Anatolia now relied upon more regular and abundant grass harvests. Some of them had even settled into permanent villages of two or three thousand people living in tightly packed clusters of unbaked-brick houses. Their sickles were now more refined and they stored their heaps of grain in vessels to resist the teeming mice, drawn to the easy food found in the first human settlements. Cooks had already invented new techniques and recipes particular to cereals: Mix and mash warmed, malted grains, then add water and leave the brew until it bubbles into a thin, yeasty porridge—a precursor of beer. Grind wheat into flour, then moisten and mix it into a dough and throw it onto the fire, until it bakes into bread.

|

The precise timeline of agriculture in South Asia remains largely unknown, due to paucity of early archaeological remains. But evidence suggests the earliest Indian cultivators were forest nomads who—for unknown millennia—burned small plots (swidden or jhum), to grow legumes for a season, then fallowed those gardens for decades, re-wilding the swidden as forest. Over millennia, they incorporated browntop millet (andakorra, Telugu) and other native plants into their evolving swidden systems. They also practiced arboriculture, domesticating mangos, citron, even entire teak forests, beginning unknown thousands of years ago. |

Villagers also foraged other wild foods to supply half of their diet. But, instead of following migrating herds, semi-settled and fully-settled foragers focused more on fishing and trapping smaller, non-migratory animals—hares, turtles, birds, and suchlike—from nearby. Having once consumed a much broader range of plants and animals across different habitats as they roamed, now they had only what was seasonally available in their fixed vicinity. As this likely increased their dependency upon stored grain, they tended and managed the nearby grasslands, promoting the abundant growth of their favored grasses within the extant ecosystem. But feeding ever more mouths from a fixed location was still risky. Productivity depended entirely upon rainfall.

Artist’s depiction of a Natufian gatherer-hunter, 12.5–10 thousand years ago, with jewelry based on archaeological finds from El Wad in what is now Israel. Photo: Brandon Spilcher

By 7000 BCE fully settled forager-gardeners across Anatolia were also growing peas, chickpeas, flax, and a few other species in their communal wheat and barley fields, where they broke the soil for more invasive planting. This caused ‘weeds’ also to spread, but these ultimately helped to maintain soil health, fix nitrogen, and resist blight. Birds and bugs and other animals ate some of their produce. They also contributed fertiliser, helped pollinate, and aerated the soil. But to get more fertiliser for their gardens and more meat in their diets, some communities experimented with penning pigs or goats in their villages, the first domesticated ‘livestock.’ All this made for heavier work than their nomadic ancestors had done, but they still did it communally, innovating social institutions and ritual practices intended to maintain what archaeologist Ian Hodder has called their ‘aggressively egalitarian’ sociopolitical structure.

Living in this manner of sedentary abundance, they were having more children compared to nomadic peoples, who prefer to space children several years apart (since they must carry them). With higher birth rates, villages of Anatolian gardeners mushroomed and multiplied, expanding across the Bosphorus, following along river courses that would lead them over the next thousands of years into Central Europe. Some were also crossing the Mediterranean, stepwise by simple watercraft, colonising the previously uninhabited Cyclades Islands and Crete, eventually reaching the Peloponnese peninsula.

They carried their crops and animals to their new lands, maybe leaning more heavily upon farming, less upon foraging in increasingly unfamiliar territories. And as they went, they displaced the nomadic foraging populations of Europe. Only along the Nile River and in Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, were the local peoples attracted to the idea of growing grain themselves. Here many foraging communities were already living in fully or semi-settled villages. Their well-watered regions in the warm climate were so richly abundant that the grains would merely be a bonus—at first.

|

Communities inhabiting grasslands along the Gangetic plains were already promoting the abundance of native wild cereals before 13,000 BCE, hinting at multi-millennial domestication paths for millets and rices in the subcontinent. However, these communities didn’t build dense urban settlements. Rather, South Asia’s first towns arose in the Indus Valley, from 3300 BCE, founded upon wheat, barley, and cattle. Those grains were probably carried into the subcontinent by goat pastoralists migrating from further west well before 7000 BCE, prior to local cattle domestication. Advertisement |

These changes in lifestyle—sedentism, brick making, farming, and other novel experiences—cascaded into dramatic changes in how people spent their time, how they structured their social ties and ritual lives, how they assigned value to people, ideas, activities, and things. Their stories of themselves, their cosmologies of meaning, transformed to reflect these changes. Mesopotamians would eventually develop the first linguistic writing system. And the peoples of the Fertile Crescent would leave behind the oldest surviving written tales, which became a primary source of the cultural narratives that continue to dominate the world up until the present day (more on this ahead).

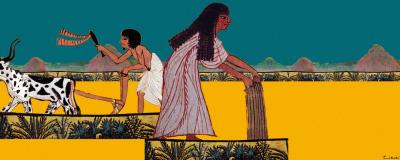

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Grass seed cultivation in Mesopotamia remained easy for a long time. Settled villagers had only to toss some seeds on the seasonally renewed, deltaic floodplains, while they continued to fish and gather wild plants and small animals. Nomadic pastoralists of the region could also spread these grasses even while continuing their seasonal migrations with their goats. Given this easy surplus of food, the settled populations swelled beyond anything anyone had ever seen before; new settlements cropped up left and right across the delta. By 4000 BCE, a Mesopotamian town might house upwards of fifteen thousand souls—among the largest clustered populations in the world, when the vast majority of people still lived as nomads. But all that easy grain no longer stretched as far. Fishing, trapping, and other subsistence activities were also proving inadequate, as the landscape was picked clean sooner each season. Resources that took more time to replenish, like firewood, were becoming scarce. Mice were becoming major pests.

Townsfolk could spread more seeds over larger areas, but merely expanding this simple method gave diminishing returns. Out of necessity, they began to cut down the surrounding forests for firewood, further driving off the animals upon whom they’d relied for meat, whose antlers, bones, claws, sinews, and other parts they used for their tools and adornments. Deforestation also altered the rivers’ patterns of siltation and erosion, leaving their fields and settlements more vulnerable to inundations. In attempting to continue their way of life with more and more people, they were destroying local forests and wetlands. They were beginning to overshoot the carrying capacity for their local environment.

When they built watercraft to help them harvest trees further upriver, they didn’t run out of wood, but the river’s flow became increasingly unpredictable and the advancing loss of tree cover potentially altered rainfall patterns as well. When they decided to plant above the floodplains, clearing and ploughing the land, digging canals to redirect water into these dry fields, they produced more food in the short term, but the deep tillage destroyed the topsoil and irrigation left salt residues, rendering the land fruitless after some years. Ironically, these townsfolk were now working much harder than their foraging ancestors had ever done, yet were left with a narrower, less nutritive diet and a greater vulnerability to famine, as their mono-cropped fields fell increasingly to pests and blight.

They penned more goats, sheep, and cattle inside their cities, but then fell victim to a rash of new zoonotic diseases. Archaeologist Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat mentions tuberculosis, typhoid, and smallpox that first passed into humans during this time. Political scientist James Scott observes that such epidemics regularly drove entire settlements to collapse, through mass death and abandonment. Meanwhile, nearby meadows were denuded by overgrazing, rendered into dust.

As farmers were working harder to keep their intensive subsistence program afloat, they yet grew entirely dependent upon their cultivated foods. Their attention turned away from broader ecosystem nurturance to focus on maximizing short-term productivity among their few domesticated species. Their foraging skills atrophied. They forgot the spirits of animals and trees to whom they’d once felt a meaningful kinship. Their ritual focus shifted skyward, as rain and weather now commanded their collective fate. These farmers were no longer fluidly adjusting their lifestyles and social structures to fit the dictates of the land, as their foraging ancestors had once done. They now sought to reshape their environment to fit the dictates of their society and its dominant ideologies, which increasingly viewed urbanism and agriculture as superior to other ways of life.

Archaeologist David Wengrow reminds us that, though the earliest Mesopotamian cities were already dependent upon long-distance trade for essential commodities, from wood to metal to stone, fiat money yet remained unknown. Grains and goods and metals were traded between cities or with nomadic pastoralist communities. Those mobile groups could ply trade between the cities and the hinterlands, where foraging communities continued to thrive, able to supply certain raw materials from forests or mountains.

But within each city, markets and trade did not direct the economy. Rather, all lands and herds belonged to the deity residing in the central temple, and were communally worked. The needs and routines of daily life were disparately organised through separate kinship groups, likely still based in networks of mutual aid that provisioned individuals. This city-wide joint tenureship of production with distributed governance functioned in service to the city’s deity. Feeding the gods was understood to be the true purpose of agricultural labor, the ideological basis shaping their economy.

But reliance on cereal and animal farming was driving a commensurate reliance on complex processes, technologies, and social institutions. Families increasingly specialised in trades, developing new skills and knowledge, revising the social relationships and networks of obligation that would have defined their distributed gift economies. And as, over centuries, this technological and social complexity escalated, production and redistribution of provisions became increasingly driven and organised by the temple. The centralisation of goods, knowledge, and power intensified. Temple functionaries invented writing to administer these complex logistics of labour, production, and redistribution.

In this changing social world, individuals’ roles were narrowing, delineated by one’s contribution within the urban project of servicing the temple. Ritual specialists—priests and temple workers, scribes, and perhaps artisans who knew the magic of refining gemstones or forging copper used in ritual—increasingly commanded status. Familial inheritance of specialised knowledge, skills, and associated status was shaping the rise of differentiated social power. Eventually, low-status subjects came to be meagrely provisioned by the state, while hereditary elites began to claim exclusive rights to particular fields or ponds, acquiring private wealth. A family with means could handsomely gift a scribe to admit their son or—rarely—daughter into scribal school, a privilege securing them a higher position on the urban ladder. And as cities were increasingly sacked by nomadic raiders, who were beginning to command the hinterlands, warfare was also becoming a feature of urban life.

In service of propitiating their deity, city rulers strove to maintain elite power within a productive social edifice. They kept copper, silver, gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian and other magical ingredients flowing from distant cities and the hinterlands toward the temples to create and consecrate more divine statuary and ritual objects—effectively a system of hoarding in which the temple became the site of accrual. They provisioned meat to feed their deity, commissioned temples, city walls, irrigation canals, record-keeping, and more. All this required more workers and more grain.

However, in overshooting their environmental limits, most cities collapsed within a few generations. Their people variously scattered to find place in other cities or to found new ones—or they dispersed among the roaming tribes, to become pastoralists or raiders. As it was, the main remedies left to avoid urban collapse were for cities also to raid their neighbors, stealing resources, treasure, and workers; to enslave nomads from the hinterlands for their labour; and to conquer new territories. It was in this context that some men ascended as the world’s first kings—considered demigods—in Sumer around 2900 BCE.

For the first time, a few elites were able to co-opt the labour of armies of subordinates. Legions of men worked in the fields, while women of similar status sat indoors, grinding grain or spinning wool. These women were especially vulnerable to control under such conditions; processing grain and raising children took up all their time and energy, while the changing configurations of social spaces had increasingly marginalised them, limiting their regular participation in public discourse. Men worked the plows and tended the herds, administered the bureaucracy, and waged war. Though some women still worked alongside men in the temples as priests, scribes, or sex workers, the broader social, cultural, and economic contributions of women were steadily being constrained, silenced, and devalued against the ascendent powers of men.

|

Sometime after 2500 BCE, semi-settled or fully settled forager-gardeners at various sites on the Deccan began absorbing domesticated crops and animals from western Eurasia and later Africa, also hybridising local rices with eastern Eurasian strains. When city-states later began to arise on the peninsula, some communities fled their vicinity, adapting swidden to mountain geographies. Swidden remained a relatively sustainable lifeway for many Adivasi groups until modern times. However, as official policies have restricted Adivasis’ usage of their lands, fallowing periods are reduced, diminishing sustainability. |

Malnutrition increasingly stalked the land—especially iron deficiency, which most acutely afflicts women of childbearing age. The masses were overworked and underfed, evident from the work-related injuries and malnourishment that marked their bones—absent from the bones of their foraging contemporaries, who lived outside the city walls. Their cereal-heavy diet promoted tooth decay. Crop blight or drought multiplied seasons of famine. As societies locked themselves into large-scale agricultural systems, they endured suffering at magnitudes unknown to nomadic foragers. And they died much younger. Meanwhile, the once Fertile Crescent was being incrementally transformed into a land of dust.

We might recognise this path of decision-making as a progress trap or, in systems-theoretic parlance, a story of Fixes that Fail: devising complex solutions to problems which then cause more complex problems, to be answered by increasingly complex solutions, until the system is so rigid and over-leveraged that it’s vulnerable to collapse.

Urban-scale, fixed-field, cereal farming independently emerged also in eastern Asia and Central America. From these origins, agricultural, statist civilisations—led by similar compulsive and propulsive logic—began spreading themselves across the continents. As they grew, they cleared forests, altered landscapes, destroyed ecosystems. They forcibly displaced or absorbed nomadic peoples and conquered rivals, as their cultural narratives evolved to justify and further compel this way of life. Conquest itself became an ideology and an economic paradigm. By five hundred years ago, this process took on a virulent new form in European colonialism, made more zealously extractivist by the emerging ideologies of capitalism and then accelerated and intensified by the burning of combustible fossils. It was this juggernaut that spread agricultural and then industrial statism farther and faster around the globe, finally carrying it to the last corners of the Earth only within the past few centuries.

But the stories from ancient Sumer already encompassed beliefs and values that we might recognise as basal to our modern mythologies: They already valorised urban life and statism above all other sociopolitical arrangements. They already accepted social inequity and believed elite concentrations of power were divinely justified. They celebrated the dominance or triumph of powerful male individuals over multitudes as virtuous and heroic. They elevated deities conceived in the human image and claimed humans were a special creation of god, intended to dominate the non-human world, granted sanction even to destroy it in fostering human power. How distant were these stories from those of their foraging ancestors and contemporaries!

And such notions yet remain substrate to industrial age mythologies, for instance, in common presumptions about human entitlements to ‘nature,’ which is conceived as something separate and inferior to humankind. Or in our imagining the human experience as exceptional, nearer to the divine. That human potential is godlike and limitless. They resonate in the belief that patriarchy and other modes of sociopolitical inequity are inevitable. And that statist institutions are truly the telos and pinnacle of human achievement—indeed, of all creation. They inspire mythologies of endless economic growth and undergird our presumptions that hierarchy, competition, and conquest characterise an inescapable and even divine human destiny—a colossal folly that’s now hurtling us toward our possible annihilation. This is the topic I pick up in the next essay.

Usha Alexander trained in science and anthropology. After working for years in Silicon Valley, she now lives in Gurugram. She’s written two novels: The Legend of Virinara and Only the Eyes Are Mine.