There is Still Some Omid

The critically endangered Siberian Crane used to be distributed in three sub-populations, of which one would spend winter in India. Despite the best efforts of all involved, the Indian sub-population went extinct in 2002. Two years ago I had done a story on this titled, "Omid no more" that took off from the name of a lone male Siberian crane named ‘Omid’ – Farsi for ‘hope’ that was wintering alone in Iran for 15 years.

Omid, the last Siberian Crane of the Iranian sub-population. Photo: Keramat Hafezi Birgani

In 1978, a yet unknown sub-population of just 14 Siberian Cranes were discovered by Dr. Ali Ashtiani wintering at Fereydunkenar wetland in Iran where local people trapped wild ducks and geese. This was nothing short of a miracle. In 1985, Dr. Yuri Markin attached a satellite transmitter to a male crane in Iran to discover a new breeding ground of this bird in Siberia. The Iranian sub-population unfortunately followed the same trajectory as the Indian one.

By 2002 only four birds remained, the population continued to dwindle and soon only one pair, the male named Omid (“hope” in Persian) and female Arezoo (“wish” in Persian) remained. In 2006 or 2007 only Omid returned, he had lost his mate Arezoo. Reintroduction programmes in Russia failed to revive the population.

Omid, living up to his name, has since appeared each autumn, spending four winter months in Iran consecutively for the past 15 years, making him the only known survivor of the western population of Siberian cranes in the wild who retains the ancient knowledge of the migration route. No one knows Omid’s exact age, in captivity, their lifespan has been recorded up to about 70 years, lifespans in the wild are shorter. The continued presence of Omid in a certain area every winter has made it possible to protect and help him at least when he is in Iran. His migration path is over 5,000 kms and there are many dangers on this route. His survival so far is a miracle and a cause for hope. However, in the absence of a female, it was just a matter of time before this population would be extinguished forever. I had thus ended my article on a note of foreboding.

However, I recently came across an astonishing update. At the end of this winter, Omid had flown back not alone, but with Roya, a female Siberian Crane! The Cracid & Crane Breeding and Conservation Center, (CBCC) in Belgium had brought up Roya – meaning 'dream' in Persian – in captivity at their facility and with the Iranian government and other stakeholders, had released her in stages with Omid. And after they spent part of the winter together, they flew back together.

Through a network of phone calls and Facebook messages – thanks to conservationist Gopi Sundar and Taej Mundkur – I was able to contact Keramat Hafezi Birgani, the head of the Khuzestan Biodiversity Group. I emailed him to immediately receive a response accompanied by his detailed report ‘Hope and effort for the dream of life and survival’ that appeared in the Middle East Crane Conservation Group Newsletter, 2023 Volume 1.

Roya, the captive bred female released alongside Omid with the blue ring on one of its leg. Photo: Keramat Hafezi Birgani

In 2022, George Archibald of the International Crane Foundation (ICF) had informed Keramat that there was a suitable Siberian Crane female at the CBCC. Keramat helped connect the CBCC and the Department of Environment (DoE), Iran and the ICF was requested to help Iran. The CBCC, with many years of experience in breeding Siberian cranes and other endangered species, opened and maintained valuable communication and cooperation with the DoE. The planned release of Roya was potentially the most crucial initiative to save the Iranian sub-population and a big step for the survival of the species.

Quite aptly named Roya, the seven-year-old female Crane was in perfect health. On arrival, Roya was placed in a special release cage near Omid’s habitat. The birds started interacting almost immediately. After closely monitoring the two together, their interaction, calls and behaviour, Roya was released on January 31, 2023. In a dream-like sequence, almost immediately on release, both cranes called beautifully and danced together, soon the birds started to fly, explore the wetlands and feed together. In the early days of the release, Omid came from north of the wetland to see Roya and stayed a few hours, the time spent together increased every day, and soon Roya flew with Omid to roost in the northern areas of the wetland.

Siberian cranes of the CBCC are descendants of the cranes of the western population of Russia. Roya, though captive-bred, was raised with virtually no contact with humans, this was crucial for her re-wilding. Her vigilance and natural instinct were excellent, after soft release, she was alert and fresh, she fed on food from the appropriate environment, and also adapted against the dangers of wild such as the night, the fog, predators like the Golden Jackal, Jungle Cat, Eurasian Otter, as well as birds of prey such as the White-tailed Sea Eagle, Greater Spotted Eagle, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Northern Goshawk, and Black Kite.

She bravely adapted to the wilderness and benefited from Omid’s company. As the end of the winter migration came closer, they flew together around the wetland, they danced and called. The morning of March 5, 2023, was sunny and calm, everybody involved watched with bated breath. Omid had arrived in Iran on October 27, after 130 days of wintering which included 34 days with Roya, Omid and Roya took off together and started their spring migration, passing the Sorkh Rood Lagoon on their long and perilous flight from Fereydunkenar wetland to Western Siberia. The toughest section of this marvellous journey had just begun, anything could happen.

Omid and Roya soon after Roya’s release. Photo: Keramat Hafezi Birgani

After the euphoric start, the team confronted their first real roadblock. Roya was seen alone on the migration route, fortunately she was healthy. On March 12, 2023 she was successfully captured for safe keeping. While there was disappointment, it was also true that all was not lost. Most importantly, Roya would have the opportunity to be with Omid again in the autumn of 2023 with the hope that they will be successful the second time.

Omid summers in a vast area and finding him is like finding a needle in a haystack. All the same, Russian collaborators had expressed their readiness to release young Siberian cranes from their Oka Crane Breeding Center into Omid’s summering area, with the idea that they might join him on his journey to Iran. The CBCC had also announced its readiness to donate Siberian cranes that will be born this summer to Iran to be released in autumn 2023 to potentially accompany Omid and Roya on their journey back. All these measures depend, of course, on the safe return of Omid, which if all goes as normal is just a few weeks away.

A brief history of release attempts that did not succeed

Roya’s release was not the first attempt to revive the crane population. According to a report, from 1991 to 2010, a total of 139 Siberian Cranes that originated from captive-produced eggs have been released at the breeding and wintering grounds.

While there were unconfirmed reports of banded cranes along the migration route several hundred kms from their release area, none of these cranes were observed on the known wintering or summer grounds. The vast inaccessible nature of the Siberian wilderness, low human numbers and high costs to survey and satellite-track only add to the difficulty. This has also made it difficult to evaluate the success of the release experiments.

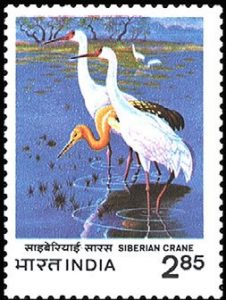

A stamp issued in 1983, when hopes of saving the Indian sub-population of the Siberian Cranes were still high. Photo: Special arrangement

Of these 139, over several years, 10 juvenile captive-reared cranes were released in late winter near the wild ones at Keoladeo National Park (KNP) in India. While their feeding behaviour and daily activities were similar to the wild cranes, they did not socialise extensively with them and did not migrate.

Perhaps the late winter releases did not allow enough time for the released birds to develop enough social bonds with the wild ones for them to fly together and disappeared due to a variety of factors. The experiment, however, confirmed that captive-reared cranes could survive in the wild throughout the year at KNP, but it unlikely that they could breed at such southern latitudes. The last wild pair of Siberian Cranes wintering in India did not return in 2003 and the attempts at KNP came to an end.

The story in Iran is not very different. Two adult captive parent-reared males were released in winter of 1996-97 in Fereydunkenar. Quite like in India, they did not join the wild cranes and did not migrate. One of them was recaptured and held in captivity but it died in 2006.

Release was resumed in winter 2002-03. A total of 11 captive-reared cranes were released at Fereydunkenar. All were ringed with colour plastic bands, three were also fitted with satellite transmitters which stopped working after a short time or just after migration started. Three of them died and eight started migration along with wild cranes. One crane released in Iran in winter of 2007-08 was sighted in spring 2008 at breeding grounds in Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Region of west Siberia, however none of the cranes returned to the wintering grounds.

Peeyush Sekhsaria, is a Delhi-based architect-geographer and independent development consultant.

This article went live on October eighth, two thousand twenty three, at forty-one minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.