We Dimmed the Dark. Now Lights Disrupt Nature.

Light has long stood as one of humanity’s greatest discoveries. Tales of scholars burning midnight oil remind us how light became a constant companion of knowledge and achievement. In recent times, it has also turned into an inseparable ingredient of celebration – a symbol of festivity and joy.

Yet before oil lamps, candles and, much later, the invention of light bulbs and LEDs, Earth was an entirely different place for life to survive. For nearly three or four billion years, life evolved while following the natural rhythm of bright days, dark nights and twilight.

The overlooked darkness of light

However, with the advent of modern lighting, we have extended brightness deep into the night – even into places once touched only by starlight or the moon. Ecologists study this phenomenon as Artificial Light at Night or ALAN, which refers to human-made illumination that persists after sunset.

From streetlights and car headlights to glowing billboards, urban skylines and festive displays, artificial light now reaches forests, coasts and even the open ocean. In many ways, it alters how creatures move, hunt, rest, migrate, reproduce and simply exist.

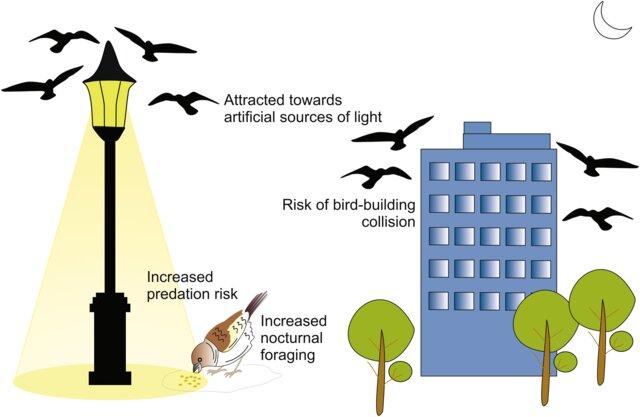

Summarising effects of exposure to light at night on migratory birds. Illustration: Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology.

Put differently, this artificial brightness disrupts the natural ‘lightscape’. Birds begin to sing at unusual hours, insects swarm and die around lamps and nocturnal species lose their way.

For migratory birds, bright lights can be deadly. During their long journeys, they rely on natural cues, such as the stars and the moon, to navigate. But in overlit skies, these celestial guides are masked, leaving birds disoriented. At a lighthouse in Canada, researchers once recorded more than six hundred bird deaths in a single migration season.

Across North America, an estimated four to five million birds perish every year after colliding with illuminated towers, their supporting wires or even with one another in confused flight. Many of these are already species under population stress and, among them, twenty species of conservation concern lose over 10,000 individuals annually.

Screenshot from a YouTube video uploaded by Benjamin Van Doren: Birds, appearing as bright specs, fly, disoriented, through intense lights during New York’s 9/11 Tribute in Light.

Festivals and darkness

In India, bird migration takes place throughout the year. However, the winter migration is particularly significant, bringing species from thousands of kilometres away to the country’s comparatively warmer regions. Delhi alone hosts at least 141 species of winter migratory birds each year. What makes this movement especially critical is its timing, especially since the city is over-illuminated by the harsh brilliance of modern LED lights and floodlights.

Also read: Of What do the Birds Sing?

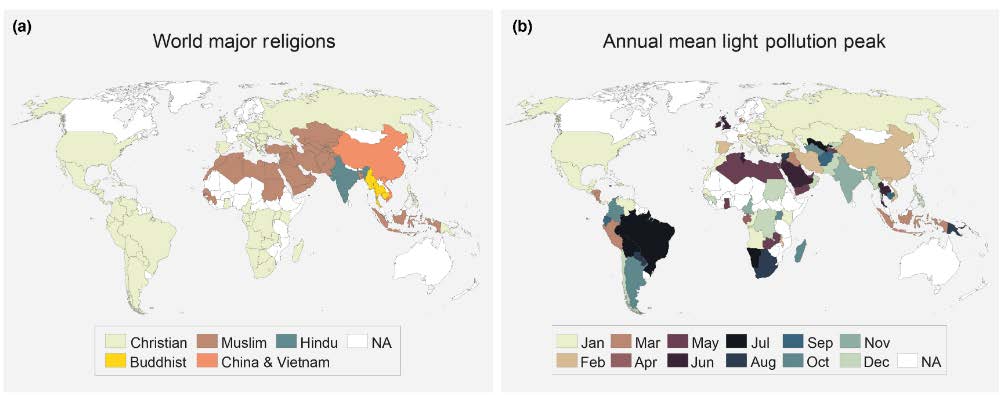

A 2023 study indicated that decorative lighting for festivals and increased evening or night-time activities during major celebrations are key drivers of global patterns in artificial night illumination. Large social festivals such as Christmas, Ramzan and Diwali contribute prominently to annual peaks in global night light emissions.

Researchers have found that night-time light peaks in Hindu-majority countries are concentrated in October–November, aligning with the festivities of Diwali. Source: Ramirez et al.

And these celebrations don’t end with the festivals; they stretch into the New Year and are followed by hundreds of thousands of winter weddings. This prolonged season of illumination, from November to March, overlaps with both the arrival and the reverse migration of birds.

Although research on the effects of ALAN on birds in India, particularly in Delhi, remains limited, evidence from other parts of the world paints a worrying picture.

Interdisciplinarity and introspection

This is a call for key insights, grounded in ecological reasoning, that can guide solutions at both regional and local levels. For instance, the European Union, through legal directives, commits to the "conservation of the species of wild birds naturally occurring in the European territory of the member states". Moreover, in 2023, the European Light Pollution Manifesto further highlighted the wide impacts of light pollution and provided mitigation measures.

Regional bodies that include India can learn from these binding frameworks. They can formally recognise ALAN as an environmental stressor and integrate controls into planning and conservation policies.

At a local level, a change in lighting type itself can eliminate up to 80% of bird deaths. Literature suggests that the effects of light pollution can be reduced by adjusting the intensity of light sources to suit their actual purpose, and that illumination can be avoided in places where – and times when – it is not needed.

Through the use of shields and suitable lamp design, light can be directed precisely where it is required. Further, reducing the emission of the harmful blue wavelengths in light is a crucial step towards mitigating the ecological impacts of nocturnal illumination.

So much can, in fact, be done.

But first, change must begin with ourselves. We must ask ourselves honestly: do we require such over-illumination to celebrate? Do our festivals call for an exuberant orchestra of light? What purpose does such exhibition serve, beyond spectacle?

We have made light an essential ingredient of our celebrations, without acknowledging the value of darkness. And yet, in our intimacy with light, we remain blinded.

Nirjesh Gautam is a researcher at the Centre for Urban Ecology and Sustainability at Ambedkar University Delhi.

(This is a revised version of a piece originally published in Urban Nature Matters, and it can be accessed here.)

This article went live on November twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.