Who Owns Tomorrow’s Emissions?

As COP30 approaches, there are increasing calls for larger developing countries to step up as providers, rather than recipients, of climate finance. While these calls may carry some merit based solely on the current emissions and economic landscape, they overlook a fundamental issue – that the rising shares of developing countries’ emissions also reflect the ongoing failure of developed countries to provide timely, adequate and predictable climate finance.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or UNFCCC enshrines the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), recognising that while all countries must act to address climate change, their obligations vary based on their economic and technological advantages, and on their historical cumulative emissions. In keeping with this principle, Articles 9.1 and 10.6 of the Paris Agreement reiterate that developed countries should provide financial support to developing countries to support their climate ambitions. However, a decade after the Paris Agreement, the world remains on track for 2.7°C of warming by the end of the century, and climate ambition – and faith in multilateral cooperation – has been undermined by industrial nationalism, divisive domestic politics, and energy security and economic concerns.

The undermining of this progress has been amplified by unclear and unmet promises of financial support from developed to developing countries to enable their pursuits of low-carbon development. After 2009’s arbitrary $100 billion target was only belatedly achieved, and while the actual disbursements are still contested, COP29’s New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) set another unclear and inadequate target. Notably, it encourages developing countries “to make contributions…on a voluntary basis” towards its $300 billion target and “Calls on all actors…to enable the scaling up of financing… to at least USD1.3 trillion per year.” Such language mirrors recommendations from think tanks for 20-30% of funds to come from non-traditional donor countries, built on the premise that the responsibilities and capacities of larger developing countries are rapidly evolving.

Countries such as China, Turkey and India feature prominently in future emissions trajectories, and the debates on reflecting tomorrow’s emissions in climate finance provision have grown more contested as a result. However, to what extent is tomorrow’s emissions curve shaped by yesterday’s unmet promises? And how therefore should financing obligations be distributed to better reflect differentiated responsibilities?

Inadequate climate finance has shaped emissions trajectories

Although developing countries will represent larger future shares of both global GDP and emissions, fuelling calls for them to “step up” as providers of climate finance, it is noteworthy first that they have already been providing such finance. China pledged $3.1 billion to its South-South Climate Cooperation Fund and reports mobilising more than $24.5 billion in climate-related project funds since 2016. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is pivoting toward greener investments, and nearly 40% of China’s overseas energy finance since 2021 has gone to renewable projects, including through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). India extended Lines of Credit worth $12 billion to 42 African countries last year, alongside allocations to Latin America, Oceania and the Commonwealth of Independent States. India has also contributed directly to multilateral institutions, with for instance paid-in capital of $738 million (and callable capital of $9.5 billion) to the World Bank as of 2023. India and China’s contributions to MDBs have also expanded the overall pool of concessional climate finance available to developing countries.

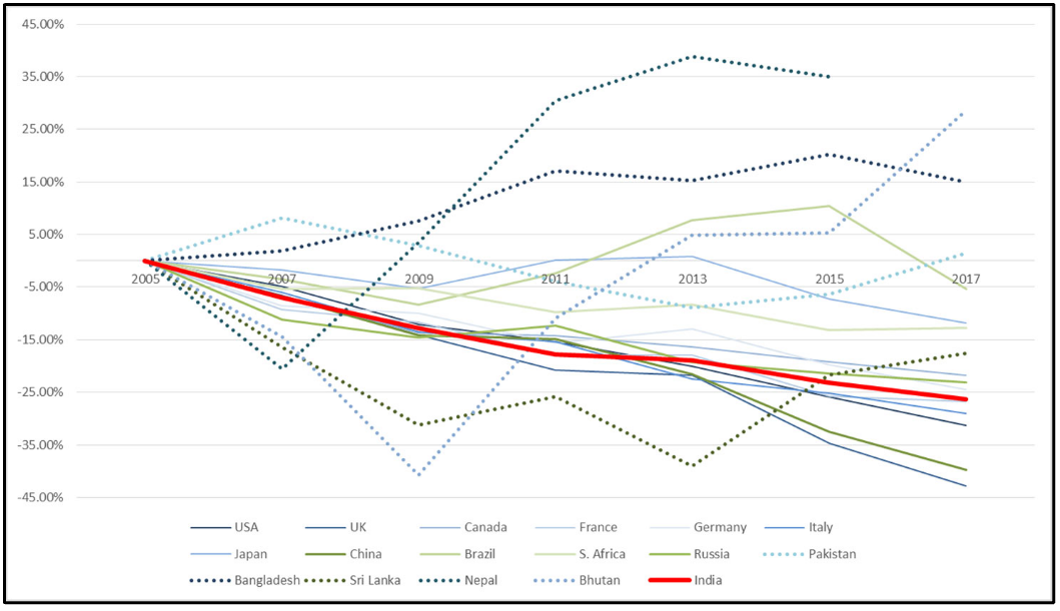

Furthermore, although China’s GDP has expanded nearly 12-fold since 1992, its emissions have risen about 4.4 times. India’s GDP grew seven-fold, while its emissions increased only 2.6 times. Its carbon intensity has dropped over 33% since 2005, at a pace comparable to or faster than many G7, BRICS, and SAARC members (see Figure 1). These trajectories demonstrate that these countries have already been decoupling economic growth from emissions.

Changes in emissions intensities across G7, BRICS, and South Asian countries. Source: https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/human-development/pledges-plans-and-actions-an-analysis-of-india-s-panchamrit-pledges.html

A closer look at emissions scenarios for India shows that its current emissions are evidently lower than the business-as-usual (BAU) emissions that were projected for 2025 by older modelling studies in 2009-15. This has enabled more recent BAU scenarios to project lower emissions trajectories going forward. However, the current emissions are still higher than the ambitious scenario projections for 2025 in the older modelling studies.

The lower emissions than earlier projected have been achieved despite persistent finance shortfalls. Estimates indicate needs of $834 billion from 2010–2030, and $170 billion from 2015-2030, to pursue a low-carbon trajectory, yet cumulative international flows through UNFCCC mechanisms have amounted to just $1.16 billion to date. Even with a broader definition of climate finance, India’s annual flows for 2021-22 are estimated at about $30 billion. India has thus bent its emissions curve below older BAU projections despite unmet international public financing needs, relying largely on its limited domestic resources, yet this curve has not been bent by as much as might have been possible with greater financial support.

India’s emissions trajectories under older and more recent modelling studies. Source: Authors’ analysis

Had its finance needs been met, India could have invested in low-carbon technologies and processes sooner, and may have had the opportunity to lock in to a lower emissions trajectory. OECD scenarios further reinforce that, had developed countries delivered their promised USD 100 billion annually from 2021, clean energy would have scaled faster. Investment would have followed sooner, and such investments early on can jump start transformations. The finance shortfall, therefore, plausibly helped lock developing countries into higher-emission paths.

Meanwhile, developed country choices compound these challenges. Nearly two-thirds of climate finance provided to developing countries takes the form of loans, often at non-concessional rates, deepening debt vulnerabilities rather than alleviating risk. Moreover, subsidy races such as the US Inflation Reduction Act and EU Green Deal Industrial Plan have spurred clean energy investment domestically but risk crowding out finance and technology flows to the South. Trade measures such as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) externalise the decarbonisation costs, effectively passing the burden of decarbonisation to exporters in the developing world. Taken together, these dynamics reinforce an uneven playing field that lock developing countries into either high-carbon trajectories to sustain their growth, or precarious fiscal situations that undermine such growth.

Taking greater responsibility and reviving multilateral cooperation

The fundamental issue then is that the rising emissions projected for developing countries are as much the result of inadequate international public finance support as of their own domestic policy ambition or implementation. Future developing country responsibility cannot be decoupled from past developed country neglect.

Climate change is a global problem, but one that will only be addressed subject to national capabilities and opportunities. To continue fostering greater climate action and rebuild trust in multilateralism, it is essential for developed countries to demonstrate greater commitment to the principle of CBDR-RC. While developing countries should certainly continue undertaking greater climate actions – in their own interests, enabled by their greater capacities – developed countries should not demand climate finance contributions from developing countries before first correcting their historical imbalances in good faith. To that end, they must take greater accountability of the NCQG, while reforming minilateral partnerships, to actually respond to the needs of developing countries. The future of multilateralism may hang in the balance.

Aman Srivastava is Fellow and Coordinator, Climate Policy and Nikita Shukla is Research Associate, Climate Policy, at the Sustainable Futures Collaborative. Views are personal.

This article went live on October twenty-third, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-nine minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.