Neoliberal parties, the corporate media, a conservative judiciary, oil lobbyists, the white elite and right-wing groups, with generous help from outside, have ganged up to derail the country’s government. And it’s all being made to look like a popular uprising against a corrupt regime

President Dilma Rousseff, who is herself under attack from the combined opposition, flew to Sao Paulo to stand with Lula. Credit: Ricardo Stuckert

Sao Paulo: In November 2009, The Economist put Brazil on its cover. Brazil Takes Off, read the headline, emblazoned on a photo of Rio’s iconic statue of Christ the Redeemer rising above blue waters like an inter-stellar rocket. Predicting that “Brazil is likely to become the world’s fifth-largest economy, overtaking Britain and France,” the magazine said that South America’s largest economy should “pick up more speed over the next few years as big new deep-sea oilfields come on stream, and as Asian countries still hunger for food and minerals from Brazil’s vast and bountiful land.”

In 2009, even as the world was reeling from a catastrophic financial crisis, The Economist saw Brazil as the great hope of global capitalism.

Back then, the British magazine was not the only one in love with Brazil. Under Lula da Silva’s leadership, the country was witnessing unprecedented prosperity and social change. Lula’s personal rise from shoe-shine boy and motor mechanic to the presidency of the biggest Latin American country was the stuff of legends. He was the subject of several books and a Brazilian box-office hit. At the G-20 summit in London in April 2009, US president Barrack Obama called him the “most popular politician on earth.” And with two of the biggest sporting spectacles – the FIFA World Cup (2014) and the Olympics (2016) – scheduled to happen in the country, Brazil, perennially branded the “country of the future,” finally appeared to be arriving on the global stage.

Seven years later, Brazil is looking like a completely different country. Lula, who retired in 2010 with an 80% approval rating, was detained this month for questioning in a multi-billion dollar corruption scandal that has seen some of his Workers Party (PT) comrades go to jail. His successor, President Dilma Rousseff is facing impeachment in the Congress. The country’s economy shrank by 3.5% last year, and this year won’t be any better. Inflation is in double digits and hundreds of thousands are facing unemployment. Millions of people have taken to the streets – both in support of and opposition to the government. No one cares two hoots about the Rio Olympics, which are less than five months away. And the corporate media – global and local – has already written off Lula, Rousseff and Brazil.

The Brazil story began to lose some of its shine in 2013, especially in the eyes of international business media. In September 2013, The Economist put Brazil on its cover once again. The report was scathing and blasted Rousseff, who had been running the country for three years by then and was facing an election the next year, for doing “too little to reform its government in the boom years.” It took Brazil to task for “too many taxes,” “too much public expenditure” and paying pensions that were too “generous.”

That had not been a good year for Brazil. The economy was faltering and hundreds of thousands of people had come out on the streets just ahead of the FIFA Confederations Cup to protest against corruption and demand better public services. The economy appeared to have stalled entirely.

So what went wrong between 2009 and 2013? How did Rousseff, declared the most powerful woman in the world in 2010 by Forbes, suddenly become weak and incompetent? How did the Brazil story turn from one of hope to that of despair in such a short time?

The answer is simple – oil, and the money, power and politics it generates.

Same old, same oil

In 2007, Brazil discovered an oil field with huge reserves in a pre-salt zone below the ocean surface. Within a year, the country had uncovered oil and natural gas reserves exceeding 50 billion barrels – the largest in South America. Brazil was now the new darling of the world’s oil merchants, and Wall Street.

State-owned Petrobras had enjoyed a monopoly over oil exploration in Brazil since its creation in 1953, but the sector had been opened up to Royal Dutch Shell in 1997. With the oil finds of 2007-08, global giants like Chevron, Shell and ExxonMobil were eyeing Brazil in the hopes of lucrative contracts. But no deals could be struck.

In 2007, Lula partially restored Petrobras’s monopoly over Brazilian oil. Laws made under the guidance of Rousseff, who was Lula’s chief of staff, gave the company sole operating rights, with all its earnings going to government’s social programmes on education and health. Petrobras also began partnering with state-owned oil firms from other countries, mainly China. (ONGC and Bharat Petroleum too are partners of Petrobras and have offices in Rio, the headquarters of the Brazilian company).

The US State Department and Energy Information Agency (EIA) soon began lobbying Brazilian officials on behalf of American companies. In secret US diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks in 2010, it was revealed how the Americans were worried about the presence of state-owned Chinese companies in Brazil, with one cable detailing how the US was trying to get the country’s laws changed to its advantage.

Brazil was soon in election mode to choose Lula’s successor, and his party, PT, had nominated Rousseff as its candidate. The main opposition party, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), which had always supported the privatisation of Petrobras, chose former Sao Paulo governor Jose Serra as its candidate. The US was keenly watching the elections; documents released by Wikileaks show that the US was banking on Serra’s win for a change in the laws. “Let these guys (PT) do what they want. The bidding rounds will not happen, and then we’ll show everyone that the old model worked … And we’ll change back,” a 2009 cable quoted Serra as telling the oil lobby.

But Serra bit the dust against Rousseff in the 2010 election. Petrobras remained the sole operator of Brazilian oil fields and its revenue continued to go to government social programmes.

Soon, Chinese firm Sinopec became active in oil exploration in Brazilian waters as it agreed with the law that stipulated a minimum 30% stake for Petrobras in all ventures. This was the end of the West’s honeymoon with Brazil. “As their lobbying failed to win oil contracts, Brazil became a villain, like Venezuela. The US government and oil firms launched a covert attack on us. Their media followed suit,” says a senior diplomat in Itamaraty, the headquarters of Brazil’s foreign ministry, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But the government also made a mistake by placing too much hope in Petrobras and oil, forgetting that it’s a commodity whose price can go down,” he adds.

Coming to power on the promise of making Brazil a more equal society with a strong welfare state, oil and Petrobras were at the core of the leftist government’s plans to use public resources and money to fight poverty, create public jobs and bring development to remote areas in Brazil. Petrobras was not a bad bet. In 2007, the company’s market capitalisation was $190 billion. In 2010, Lula’s last year in power, Brazil had grown at 7.5 % and things were looking up. Although there was a drop in Petrobras’ capitalisation and profits in the coming years, it remained one of the biggest oil companies in the world.

But things were set to get worse.

Enter the NSA

In June 2013, Edward Snowden, a US National Security Agency (NSA) system administrator, escaped to Hong Kong with a trove of top-secret documents. In the next few months, working with journalists from various newspapers, Snowden released a series of files that showed how the US government was spying on politicians, governments, companies and social movements across the globe. Surprisingly, Brazil was one of the top targets of the NSA, which was collecting more data from here than Russia or China. The Americans claimed their surveillance was part of their counter-terrorism measures, but the documents on Brazil – and countries like India – revealed an entirely different picture. It was soon evident that the NSA’s main targets in Brazil were Petrobras and Rousseff.

Explosive revelations. Edward Snowden on the cover of Wired magazine. Credit: Mike Mozart/Flickr CC 2.0

Rouseff’s email, official telephone and personal mobile phone had been tracked by the NSA, as had every email, phone call, message and all official documents on Petrobras’s network. With these revelations, US-Brazil relations reached their lowest point. Brazilian officials were quick to say the spying was done because of the US interest in their oil and gas.

At that time, Petrobras was about to auction one of its big oilfields, with several American firms expected to participate. But as Rousseff cold-shouldered Obama at the G-20 summit in Russia and Petrobras officials accused the US of stealing information that gave them “privileged position at the auction,” negative stories about the Brazilian company and its forthcoming auction began to appear in the western media. When the auction was held, no American company offered a bid. Serra’s prediction had come true.

With its trade secrets and information about its assets downloaded in NSA facilities, Petrobras was now a sitting duck. Its fall had just begun.

In March 2014, Alberto Yousseff, a convicted money-launderer who had been arrested five times, began to sing like a canary after negotiating a plea-deal with prosecutors in Curitiba, the capital of the southern Brazilian state of Parana. He named many big leaguers whom he said had benefitted from bribery, kickbacks and money-laundering in Petrobras. Since then, the probe into this scandal, being led by Judge Sergio Moro, has singed the country’s top businessmen, oil executives and, most importantly, the leadership of the PT. Known as “Operation Car Wash,” the probe has played out like a telenovela, with big names being netted by the police or sent to jail by Moro at regular intervals.

This month, the unthinkable happened. The most popular leader in the history of the country was on the verge of being arrested for alleged corruption related to Petrobras. On March 3, the federal police picked up Lula from his house under a “coercive warrant” (which forces a person to testify in a case) and grilled him for five hours at their office in Sao Paulo’s domestic airport.

As Lula was detained and released, tension gripped the country with a section of Brazilian society – upper crust and mostly white – celebrating the police action, while the other part protested against the “coup”. Brazil was vertically divided on the day Lula was detained.

History of coups

Brazil has been a divided country for quite some time. Few people in the country accept the existence of class and racial fault-lines, but these are visible every day in Brazil’s politics and social conflicts. After years of stress, the fault-lines began to rattle in June 2013 as Brazil was gearing up to hold the FIFA Confederations Cup; thousands came out on the streets protesting against the government, with some calling for the president’s impeachment and some even asking the military to “intervene”. Ignoring the class and racial nature of the protests, the media – local and international – called it the “Brazil spring” – an uprising against a corrupt and unpopular government.

A similar narrative has been repeated in the past few days since Lula’s detention. But many in the government are seeing it as a conspiracy. “What is happening in the country is a national and international conspiracy to destroy the PT, and to introduce in Brazil an economic model like the current [neoliberal] one in Argentina,” veteran Brazilian diplomat Samuel Guimaraes told reporters after Lula was detained by the police. “This is a coup in progress.”

Brazil is no stranger to coups. Nor is foreign interference – from the US – unknown here. In the 20th century, at least three Brazilian presidents had to lose their job – and one, his life – for following pro-people policies, much to the anger of the country’s elite, and Washington. In all the cases, their fall was blamed on high inflation, falling incomes and bad economic management. There is a clear historic pattern to it. Getúlio Vargas, who created Petrobras as a state company and gave social rights to the country’s poor, was hounded by the Rio elite led by a media moghul for corruption he never committed. In 1954, he ended his constant humiliation by putting a bullet through his chest.

The next one to fall was Janio Quadros, who won the presidential election with a record margin in 1961. The same year, Quadros invited the Argentinian revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara to Brazil and honoured him with the Order of the Southern Cross. The move alarmed the Brazilian elite and Americans, who were both paranoid about the spread of communism in South America. Then Quadros, a maverick figure with no clear ideology, committed even a bigger mistake: nationalization of a huge mining company. In less than a year, he was stripped of his powers by the Congress dominated by old money, traditional elite and Washington loyalists. He quit his post and left Brasilia for reasons that remain a mystery till now.

Quadros was replaced by João Goulart. A centrist leader with progressive views, Goulart began implementing policies of high wages for the working people, agrarian reforms, voting rights to all Brazilians and social justice. As the Brazilian government took a slight left turn, John F Kennedy, who was US president and still recovering from his Bay of Pigs misadventure in Cuba, began discussing with his aides the ways of overthrowing Goulart. According to papers in the US National Security Archive, in March 1963 Kennedy told his aides, “We’ve got to do something about Brazil.” Soon after, the Brazilian media dubbed Goulart a communist and began complaining about high inflation. In 1964, on US command, the Brazilian army toppled Goulart to “save the country” from communism. Until today, many in Brazil’s elite circles refer to the coup as a “revolution”.

The world knows about the brutal junta regimes of Chile and Argentina, but it all started in Brazil – in 1964. Most South American countries were ravaged by decades of US-backed dictatorships. They began to return to democracy in the 1990s ,after the Cold War got over. Then in an ironic twist and a big jolt to the Monroe Doctrine, one country after another – starting from Venezuela to Brazil to Argentina to Uruguay and Chile — elected leftist governments. South America was no longer Washington’s backyard. In the past 15 years or so, all South American nations have witnessed sharp economic growth as they engaged with China for trade, making the Asian country the biggest player in the region.

Second time a tragedy

South America’s continuous leftward march has made the alarm bells go off in Washington once again. It has also made the local elite restless. After 13 years of PT rule, during which huge social welfare plans have been implemented, Brazil’s elite is worried sick about the “Bolivarisation” of Brazil – a reference to the leftist policies in Venezuela under Hugo Chavez. In Sao Paulo, the financial capital of South America, the cocktail circuit chatter often revolves around how to stop Brazil from “turning into Venezuela”. The anti-government protesters on the streets repeat the same slogans as they abuse anyone wearing red.

Many say that the tragedy of 1964 is being repeated. “We are facing a strategy of a coup d’etat against an elected president,” historian Paulo Alves de Lima told Russia Today recently. “We’re on the verge of a new stage of a rolling counter-revolution, of an even more restricted democracy, unbearably pregnant with arrogance and institutional violence…,” Lima told Brazilian journalist Pepe Escobar, who sees the “regime change” in Brazil as an attack on the BRICS group.

Many top Brazilian intellectuals, political observers, social activists, judicial experts and government insiders believe that unlike 1964, when the army took the lead in overthrowing the government, the current “counter-revolution” is being organised and led by neo-liberal parties in cahoots with the country’s business lobbies, right-wing groups, corporate media and “highly politicised judiciary”.

Leading the charge against the Rousseff government is the PSDB, which calls itself social democratic but is in fact a right-wing party that advocates neoliberal policies and the slashing of welfare. Having lost four consecutive presidential elections to the PT, the PSDB is witnessing a bitter feud between its leaders – who all want to be the country’s president. The party smelled a chance of victory in the 2014 elections after opinion polls projected that Rousseff has been weakened by the Petrobras scandal and street protests. In the middle of the election season, as Eduardo Campos, a popular candidate from the Brazilian Socialist Party, mysteriously died in a plane crash, PSDB candidate Aecio Neves began to imagine himself in the presidential palace. The western media projected him as a man who could save Brazil. A Morgan Stanley banker even compared Neves’ rise to that of India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi.

Neves was certain of his victory when Veja magazine published a story on the eve of the final round of voting in December 2014 claiming that the money-launderer Yousseff had told the police that Rousseff and Lula had known about the corruption in Petrobras. Yet, he lost the election. But within a month of Rousseff’s inauguration for her second term in January 2015, Neves began to call for her impeachment, still waving the Veja article as a “proof” of her complicity in the scandal.

The article, published without any response from Lula and Rousseff, was not an exception. The “Operation Car Wash” trial has been as much in the media as in the court, with regular leaks about accusations made in plea deals. The Curitiba magistrate, who is reportedly influenced by the Mani Pulite trial in Italy, has become a cult figure for the Brazilian middle-class as his photo and quotes are splashed across magazines and newspapers almost daily. But Moro, the judge, has also faced criticism for his tactics of keeping the accused in jail without bail and using plea deals to build cases against others. Even The Sunday Times of London recently ran an article on the judge, questioning the way he has been running the case.

The media-judicial complex

Moro seemed to care little for such criticism when he sent the police to detain Lula. Despite his name appearing in numerous articles linking him to the scandal, till now not a single piece of evidence has been produced against Lula – in a court or in the media. Also, the former president has never refused to cooperate with the investigation. So, when Lula was detained under the coercive warrant, many thought the judge had crossed a line. A Brazilian Supreme Court judge, Marco Aurélio Mello, publicly criticised the magistrate because “coercion would only be appropriate if Lula had been summoned and refused to testify, which did not happen.”

Despite Moro’s tough tactics, Lula’s detention did not go according to script. As soon as the news spread in Sao Paulo, fist-fights broke out between rival groups of people in front of the building where Lula lives. Then a tweet went out from the PT account saying that Lula was a “political prisoner”. With social media buzzing with news about the “kidnapping” of Lula by the police, hundreds of people jammed the streets in Sao Paulo, shouting “We will not allow a coup”. As reports of crowds gathering in other cities came in, Lula was allowed to leave. He went straight to the party headquarters and addressed a huge gathering of activists and students. “I deserve a little more respect in this country,” said Lula, looking tired but resolute. The same evening, Lula was at a meeting of unions, saying he could run for president in 2018. “I was hoping that you choose someone to run in 2018, but they poked the dog with a stick. So I want to offer myself to you [as a candidate],” Lula said at a packed square roaring with his name in downtown Sao Paulo.

Even hardcore supporters of the PT and Lula hold the party partly responsible for what’s happening in Brazil today. The involvement of party leaders in corruption has dented its image even among its followers. Besides, the party’s core support group of unions, social movements, left activists and ideologues have drifted away from the PT as Rousseff moved the government to the centre and cut herself off from these groups. In such a scenario, Lula’s arrest should have been a death-knell for the party. In the media – local and global – Lula was painted as an isolated figure. But the situation on the ground was different, with millions of his supporters rallying around him.

But there were more twists to come.

On March 11, Rousseff offered Lula a cabinet post in her government. After much discussion and delay, Lula agreed to be Dilma’s chief of staff (equivalent to prime minister). The move was seen by PT supporters as necessary to save the government from the “coup,” while the opposition was quick to brand it as an attempt by Lula to save himself from arrest in the corruption scandal. The next day, Moro released a tape of a phone conversation between the two leaders. In the wiretapped chat, the two are heard discussing Lula’s inclusion in the government. Playing it on prime-time news, Globo TV spun it as an attempt by Lula to dodge the law as federal ministers can be tried only in the Supreme Court. As if playing an unverified tape was not enough, Globo newscasters exhorted people to go out on the streets to protest against Lula and Rousseff.

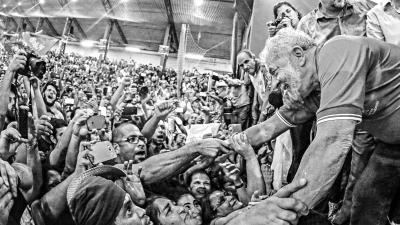

Lula meeting union activists, students and people from social movements at a gathering last Friday, after he was detained for a few hours for questioning in a corruption scandal. Credit: Ricardo Stuckert

The wiretapping of Rousseff’s phone by the Brazilian federal police, while talking to a former president, immediately triggered a comparison with the NSA surveillance. Enraged by the move, Brazil’s top judicial experts questioned Moro’s decision of recording a private conversation and leaking it to the media before it could be produced in court as evidence. But Moro justified his action by comparing it to former US President Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal.

The 30-second clip, which has no judicial value anymore, has given enough ammunition to the opposition to demand Lula’s arrest and hasten the process of Rousseff’s impeachment. Even as Justice Mello of the Supreme Court blasted Moro by calling the wiretapping of the president’s phone a “crime”, the leaked tape and Globo’s hysterical headlines had the desired effect: Lula’s nomination to the chief of staff post was blocked and protests broke out against the government.

Two Brazils, two tales

A day after the wiretapped chat was released, some 1.5 million people, almost all wearing the canary yellow jersey of the Brazilian football team and waving national flags, came out on the streets across the country. With photographers capturing the sea of yellow and green from choppers hovering over Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo, where 400,000 people had gathered in the biggest ever anti-government protest in the city, the next day’s newspapers were painted in yellow and green. It seemed the whole of Brazil was demanding the PT’s head. The narrative of “popular uprising against a corrupt and inefficient” government was back in the international media.

The truth is a little bit more complicated. Although dressed in national colours, the protest crowd was anything but national in character. A survey by Datafolha on the participants revealed that 80% of them were white, 77% had higher education and 75% belonged to high-income groups. In a country with a 50% white population, 11% with higher education, and less than 6% in top income groups, it is not difficult to guess the protesters’ profile. They mostly came from the upper crust of Brazilian society: rich, white and conservative.

The Brazilian elite has been restive with the leftist government; their favoured party, the PSDB, has been beaten constantly in elections. Under the PT’s rule, more than 40 million people have overcome poverty and joined the middle class. It has been the strongest-ever period of inclusive growth in a country notorious for inequality. Widespread social changes have occurred in Brazil. With laws that guarantee minimum wages and pensions, the middle-class can’t afford maids and drivers anymore. With quotas in education, black students are entering public universities and the professional job market in record numbers. And with rise in their incomes, the poor now travel by flight, shop in malls and buy houses in middle-class – and white – neighbourhoods. The established social order was disturbed under the PT’s rule.

A beneficiary of the Bolsa Familia programme. Credit: Ana Nascimento/Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome/Flickr CC 2.0

Few countries have seen so much social change in such little time. Just like the rich exploded in anger in the times of change under Vargas and Goulart, this time too the country’s privileged classes are seething at the PT for giving direct cash to the poor under the Bolsa Familia programme (which inspired the MNREGA in India). In his speeches, Lula often taunts the Brazilian elite for not accepting this social change and resenting the improvement in the lives of poor people. Many in the PT believe that Brazil’s crisis has been manufactured by the elite to derail the government and put in power their own people.

“The first protests against Dilma happened in 2013, when we were preparing to host the FIFA Confederations Cup. At that time, the unemployment rate was at record low, inflation was in single digit, wages were rising and Dilma had 70% approval ratings, and yet people were demanding change. It made no sense. But that was the beginning of a colour-coded regime change operation in Brazil,” says a party official who did not wish to be named. “It was all organised and promoted over social media. It was almost like an intelligence operation,” he adds.

Although there is no evidence to suggest that the anti-government protests in 2013 were engineered from outside, the crowd then too was definitely elite. A survey by Datafolha done at that time had revealed that 90% of the protestors were white and 77% had higher education. Since 2013, all protests against the government have happened in affluent and middle-class areas, far from the areas where the majority of the people live. But the media has constantly called it the rage of ordinary Brazilians.

Brazil’s media is dominated by oligarchs. Once called A Country of 30 Berlusconis in a paper by Reporters without Frontiers, there has been an open war between the left-leaning government and the media since the beginning of Lula’s first term in 2003. In Rousseff’s years, the war has become dirtier. The onslaught on the PT governments has been led by the Globo group, which runs dozens of newspapers, magazines, TV channels and websites. The conglomerate, which has a near monopoly over news, entertainment, football and the carnival, has historically been anti-PT. It had also actively supported the 1964 coup. The group made enormous profits during the 21-year army rule.

But Globo’s belligerent tone has not gone down well with poor and middle class Brazilians, with many calling for its boycott. A day after the TV channel played the Lula-Rousseff tape, famous Brazilian actor Wagner Moura, star of Narcos on Netflix, posted a video on his Facebook page, expressing concern about the “media circus” and “political agenda” of the judiciary. “The press, of course, if we look back, were all involved in the coup of ’64,” Moura said in the video.

The night of long knives

The Brazilian mainstream media enjoys tremendous power in the country, but it seldom uses it to question the judiciary. All selective leaks from Moro and the federal police are dutifully published. There have been serious charges of corruption against top PSDB leaders, including Neves, and the speaker of the Congress, Eduardo Cunha, who is leading the impeachment process against Rousseff. But the media has not bothered to raise obvious questions about these leaders. The country’s top intellectuals see a bigger problem there. In the words of Jesse de Souza, a renowned sociologist, the judiciary has taken the position of a “higher moderating force,” above politics, once occupied by the military, and before that the monarchy. “The media has enabled this,” de Souza wrote in an article last week.

For leftist commentators, the country is facing a “coup,” and the media and judiciary are working in tandem. Miguel de Rosario, the editor of O Cafezinho, an alternative-leftist website, sees a bigger conspiracy bigger than in 1964. “Similar to 1964, the current coup attempt is backed by the largest Brazilian media group, Globo. Unlike 1964, the current coup attempt is the result of an ideologically-driven judiciary that has three purposes: to overthrow a democratically elected president; prevent former president Lula from running in the 2018 elections; and ultimately making the Brazilian Workers Party illegal,” he wrote in an article.

This may sound alarming but the way things are unfolding in Brazil, there is fear in the air: fear for the future of democracy and the rule of law.

CUT, the biggest trade union in Brazil, organised a massive show of strength in an indication that the Brazilian politics will now move to streets. Credit: Ricardo Stuckert

On March 18, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people packed the streets in “defence of democracy” in 45 cities across the country. The biggest gathering happened in Sao Paulo where 250,000 people, including critics of Rousseff and Lula, jammed Avenida Paulista, despite the threats of violence from right-wing thugs. It was a show of strength against the “coup”. It was a show of Brazil’s diversity. The evening turned feverish when Lula, dressed in a red shirt, arrived on the avenue and spoke for 20 minutes, standing on the top of a bus parked across the avenue. “Nao vai ter golpe,” (we will not have a coup) shouted Lula and thousands of voices joined him. “Democracy is about the voice of the people, about the voice of the majority,” said Lula, electrifying the crowd.

Lula’s detention has energised Brazil’s left. The streets have been dominated by the right since 2013. Now, with leftists regrouping themselves many fear the worst: violence and social conflict.

The endgame

Ordinary Brazilians may be bracing themselves for street fights, but the real games are being played in Brasilia, the country’s capital. A Supreme Court judge, Gilmar Mendes, has stayed Lula’s appointment as minister. Cunha has joined hands with the PSDB to accelerate Rousseff’s impeachment. Michel Temer, the vice-president, has reportedly been discussing post-Rousseff government formation with Serra, who is now a senator. There are rumours that the impeachment process may get over by the end of April, and that Temer, who prominently figures in several corruption cases, will take charge of the country.

Brazil is on edge. A former president who transformed the country may go to jail. The current president, who faces no corruption charges, may be impeached. And all this in a year the country has to host the Olympics. But even as some worry the current crisis will cause damage to the country’s institutions and others call it a threat to democracy, Brazil’s elite don’t seem to care. In an indication of what’s cooking in Brasilia, famous news photographer Franco Ilimar published a snap of a lunch meeting on March 16, a day before Lula’s appointment to the government was stayed. In the photo Mendes, the judge who stayed Lula’s appointment, is seen having lunch with Serra and Arminio Fraga, a former manager of George Soros’ Quantum fund. The photo went viral on social media, with people wondering what was being discussed between the judge, the politician who features in the Wikileaks cables and a fund manager who represents the interest of US financial corporations.

Maybe they met to discuss football.

But with Serra, a master political strategist, at the centre of action after the humiliating defeat to Dilma in 2010, the next few weeks would be crucial for Brazil, PT and Petrobras. In Brasilia, it is being called the “do or die” battle, as political alliances on both sides of the aisle scramble to get numbers for and against Dilma’s impeachment. Dilma and Lula are fighting for their political survival and democracy, but lobbyists are already working hard to break Petrobras’ monopoly over Brazilian oil.

In the middle of all the bitter fights in courts, Congress and streets, the Brazilian senate recently passed a bill that would “cancel the requirements that Petrobras be the operator and hold at least a 30 percent working interest in all pre-salt fields”. If the bill, sponsored by Jose Serra, becomes law it will end Petrobras’s control over the country’s oilfields. Though strongly opposed by some senators like Roberto Requiao from the state of Paraná, the bill was passed by the senate by a thin majority. Surprised at the rush to privatise the oil ventures, Requiao said the whole process is being done in a “hurry without going through committees, while lobbyists are attending offices on behalf of multinationals like Shell and British Petroleum”. But in the face of massive lobbying by oil firms, Requiao’s opposition to the bill was not enough. “Has Brazil lost the majority in the Senate to the transnational oil companies? I still hope not,” the senate veteran tweeted after the vote.

Now the bill goes to Congress and then to the president for approval. Rousseff, as president, could still veto the bill. But if vice president Michel Temer, who has fallen out with Dilma, takes over from her there is little doubt about the bill becoming law. Finally, the whole Brazilian drama – Lula’s detention, Dilma’s impeachment and the hounding of PT is boiling down to oil.

As if on cue from Big Oil, The Economist put Brazil on its cover again this week. “Time to go”, says the magazine over a photo of a sullen looking Rousseff. Repeating the same old script of “economic mismanagement”, the magazine has demanded the removal from office of a leader who won a clear mandate in a free and fair election barely 15 months ago.

The Brazilian elite and media too are following the same script. Like past presidents Vargas, Quardos and Goulart, if Dilma Rousseff has to leave office, oil firms would have won. And Brazil would once again have fallen to a coup.

Shobhan Saxena is an Indian journalist who reports on South America from Sao Paulo