How 'Bandit Queen' Finally Made It to the Big Screen

“I have to declare an interest," I said.

“Ah! A contract for your grandmother again," remarked Michael Grade, chief executive of Channel 4, to whom as a commissioning editor I was pitching proposals for future productions.

“Poor Nani, dead these fifty years," I said. “No! I want to buy the rights to a book written by my ex-wife Mala Sen.”

“Definitely ex? Songs and dances around trees?”

“Very definitely and no, not Bollywood.”

I outlined the story and was granted a budget before moving on to 50 other proposals.

I called Mala and told her to get on with the script right away.

Four months later, there was still no script. Mala had spent years visiting and interviewing Phoolan Devi in jail, talking to her family and writing India’s Bandit Queen published by Harper Collins, UK in 1991. The book was a success but Mala’s attempt at turning it into a screenplay was not.

She was too engrossed in the political dimensions her researches and her own ideological determinations had thrown up, too dismissive of film as an entertainment medium rather than an instrument of social change. After hours of discussion about the form, content, structure and format of a screenplay we were no further.

We agreed on a final deadline. She produced a telephone directory of a manuscript, but it wasn’t a screenplay. It was copious pages of revolutionary argument in the mouths of ‘characters’, who all spoke like Mala.

I had a problem. The channel controller, with an eye on unspent budgets, asked me how Bandit Queen was going. Did I have a script, a production company and a director?

"Can you give me the details by tomorrow? Would love to read it,” he said.

I knew what he meant. Channel gossip had told him that the project was getting nowhere and he was after reclaiming its budget.

“Done by tomorrow,” I lied.

That evening I was supervising the recording of an Asian discussion show hosted by Shekhar Kapur. After the recording we went to a pub in Wandsworth. I asked him if he wanted to direct a film about Phoolan Devi and he naturally asked if he could read the script. I said there wasn’t one but there would be in ten days’ time but I needed a yes or no to my proposition before I drained that pint of beer. Shekhar was hesitant but by the time the meniscus of our beers neared the bottom of our mugs, he said he’d do it.

I phoned Bobby Bedi who had produced a film for me in India, a very problem laden one, and known for finding pragmatic solutions on the way. He’d be happy to produce it he said.

Phoolan Devi

A party of four set out for Bordeaux to a colleague’s holiday cottage. In between bouts of visit to the wineries of the Claret-producing chateaux, the first draft of the script was done in ten days. Then after Shekhar’s scrutiny, we worked on draft two and three, the last one in the idyll of Dalhousie in Himachal.

Ranjit Kapoor in Mumbai then translated it from my Hinglish into the colloquial bhasha of the Chambal.

Shekhar recruited Seema Biswas to play the dacoit, not a financial guarantee at the time. I was skeptical and in favour of a name that would smash the skylight of the box-office. Shekhar’s dramatic sense trumped my insistence.

The shoot progressed with ‘reformed’ bandits, some of whom had worked with Phoolan, as security guards in the badlands of the Chambal ravines. They would ride shotgun for the crew.

The script calls for a scene in which Phoolan is stripped naked in the village square by upper caste Thakurs who have captured and raped her. She is then made to walk across the village square to the well to fetch water for her tormentors. Seema refused to do a nude scene and a body double was recruited.

Without explaining his directorial strategy, Shekhar had a flimsy fence constructed all around the square. The scene’s action commenced within it and ‘Phoolan’, stripped of her ragged clothes, began her naked walk to the well. As the camera rolled, Shekhar directed the stage-hands to demolish the fence, revealing the shivering actress to the hundreds of villagers gathered behind it. Some had climbed to the roofs of the adjoining houses to get a better view of the ‘sooting’.

The camera captured their genuine astounded reactions.

In these months meanwhile, Mala, who had made friends with Phoolan was determined to crusade against the injustices of the social order had recruited an eminent lawyer to the cause of getting Phoolan out of jail. They had made representations to the courts and secured Phoolan Devi’s release.

The film was finally ready and Bobby invited guests to a private viewing in the Alliance Francaise in Delhi. The audience, he reported, were perhaps disconcerted but positive and admiring.

Also Read: Meet Shah Alam, the Young Revolutionary Continuing the Legacy of His Heroes

It came then as a bit of a shock when Bobby received a court notice forbidding the distribution of the film, followed by articles in the press accusing the producer, director and writer of traducing Phoolan’s rights by depicting the violent rapes she had described to Mala. The petitioners, one of whom had – as Bobby’s guest – seen the film at the Alliance, had recruited Phoolan to file the case to prohibit its exhibition. (Mala, as the writer, was represented in court by Arun Jaitley, now the finance minister.)

The complainants then sent a letter signed by eight or ten individuals to Michael Grade, asking him to sack me as I had done a disservice to India. Michael had seen the film and thought the letter absurd. He made a very rude remark about what he’d like to do with it and gave it to me to frame a reply.

Three of these signatories were people I knew. Two of them had had Channel 4 commissions through me, one for a feature film and the other for a documentary.

The third was a friend of Mala’s who had contracted, through a traffic accident, an infection which the doctors said could prove fatal as there was no cure. Except that there was! Through a fateful coincidence one Firdous Ali, a friend, happened to be in my office when Mala gave me the news and the name of her friend’s infection. Firdous, alert to our conversation, said his relatives, both doctors in the Midlands, were working on a cure for just that marrow disease. He called them. They said that their drug had not yet been finally tested and sanctioned for medical use, but they would smuggle some out and it could be sent to India.

It was and may have saved Mala’s friend’s life. And here was his signature asking for me to be deprived of my job. I’ve never understood the mechanics of gratitude.

The case lumbered on in the Delhi court. Channel 4’s head of finance walked into my office and complained that it was costing him millions: The insurers of the Channel’s other films had heard of the case and had raised premiums or refused cover. He pulled out a cheque book and some forms authorizing me to withdraw money from the Channel’s bank accounts.

“Go to Delhi and fix it,” he said. “Your secretary has your plane ticket, your clothes are in a bag in a taxi waiting to take you to the airport. Now!”

He walked out before I had a chance to protest. I took the ticket, taxi and flight and landed up that night in Delhi. Regardless of the lateness of the hour, Bobby called Phoolan’s husband.

“Farrukh Dhondy saheb London sey ayenh hain abhi, saath cheque-book hein..” hubby got it.

“Mein palang mey samjha deyta Phoolan ko," he said.

At seven the next morning, Bobby met the hubby at Delhi race course and my cheque for 40,000 pounds sterling changed hands with a promise of a further amount from Amitabh Bachchan’s distribution company.

Before midday, to the absolute dismay of the petitioners gathered on the steps of the court, Phoolan walked up along with a jobbing lawyer she’d picked up and asked the judge to drop the case.

In the weeks before their rout the petitioners had approached a judge at his residence on a Sunday to issue an order to the Producer’s Association of India to withdraw Bandit Queen as India’s nominee for an Oscar in the Best Foreign Film Category. So it was written, so it was ignominiously done.

Back in London I received a phone call from a person saying he was from a certain French publishing house. He asked me to delay the release of Channel 4’s film for six years and they would make it “worth my while”.

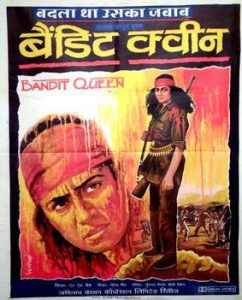

Poster of the movie

I pretended I didn’t know whom he represented and why he was making this absurd and corrupt demand, though I knew.

Inspired by the success of the Kolkata-based film City of Joy, his firm had commissioned an English writer to go to India and write a biography of Phoolan Devi which they would then sell to Hollywood. The release of Channel 4’s Bandit Queen killed that enterprise.

I said I was sorry his French firm had faced this disappointment.

“Agincourt, Waterloo and now Bandit Queen,” I said before putting the phone down.

I later heard that the English author they had sent out was a friend of one of the petitioners and lived in her flat. Oh tempora, O mores!

Phoolan now supported the film and through the notoriety or notice it brought her, stood for parliament and was elected.

The film won a prize at the Cannes film festival and when it was released in the UK London’s eminent critic began his review saying “At last Indian film comes of age!”

The film was released on January 26, 1996.

Farrukh Dhondy is a novelist and script writer.

This article went live on January twenty-sixth, two thousand nineteen, at zero minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.