Beyond the Bhadralok: Caste, Class and the Invisible Lives in Satyajit Ray’s 'Aranyer Din Ratri'

Renowned American filmmaker Wes Anderson has described Satyajit Ray’s 1970 classic Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest) as “a clash/negotiation between castes and sexes. Urbans and rurals. Selfish men and their hopes and cruelties and spectacular lack of wisdom. Women who see through them.”

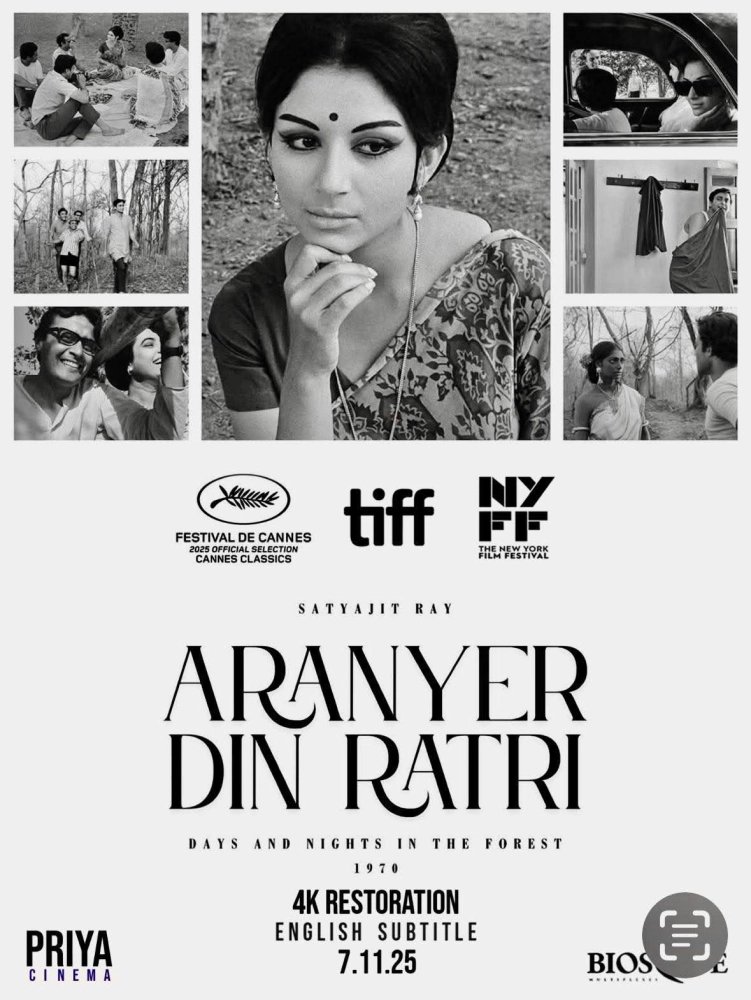

Originally released more than five decades ago, Aranyer Din Ratri has garnered renewed interest lately, with a restored version being met with a standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year and the same now playing in select theatres and multiplexes across Calcutta ahead of the film’s nationwide release.

Aranyer Din Ratri follows four young middle-class upper-caste men from Kolkata – Asim, Sanjoy, Hari and Sekhar – leaving the city for respite in the forests of Palamau, Bihar. Asim is a suave corporate executive, Sanjoy a labour welfare officer, Hari a sportsman and Sekhar the only unemployed one in the group. The plot revolves around their encounters with local tribal villagers and two women from an affluent Tripathi family – Aparna and Jaya.

In a scene in Aranyer Din Ratri, the encounter with local tribal men in a liquor shop. Photo arranged by author.

There is no dearth of previous writings on Aranyer Din Ratri, especially on Ray’s brilliant dissection of the hypocrisies of the Bengali middle class (bhadralok) at the height of the then political turmoil in the state. But what remains missing, even amidst the detailed crafting of the protagonists’ narrative arcs, is the director’s insight into the identities that stand at the margins of this film.

Few minutes into the film, the four men reach a local liquor shop. Sekhar looks at the tribal men sitting on the ground drinking together, and somewhat shocked asks Sanjoy, “Chotolok mairi! Kichu korbe torbe na toh? (These lowly people! They won’t do anything untoward, would they?)”. Though they are not in the center of the narrative, three “supporting” characters in particular become extremely significant to understand Ray’s storytelling in its context of a turbulent times – the chowkidar (caretaker) of the forest bungalow, a young tribal girl Duli and a tribal man named Lakha.

The “helpless” caretaker

The four men arrive without booking accommodations in the forest rest house. They begin first by trying to hoodwink the chowkidar and then proceed to bribe him in order to get in. Whenever they need something in the bungalow, one of them shouts with brazen entitlement, “Ae chowkidar! Chowkidar!”

The caretaker’s presence is minimal in the narrative with very little screentime. From the beginning through to the end, he is portrayed as utterly helpless. His wife has been unwell and there hangs a perpetual fear of losing his job. Being coaxed into allowing the group of men to stay in the rooms without due authorisation from the forest officer keeps him on the edge.

Also read: A Satyajit Ray Film That Foresaw India’s Descent Into Dystopia With Remarkable Clarity

This helpless state of the chowkidar, for Ray, becomes a springboard to his reflections on middle class guilt. Aparna, the moral center of the film, in her conversation with Asim, expresses concern over the precarity of the caretaker’s life and his possible retrenchment. Further on in the film, while walking together, the two hear a child crying from the caretaker’s quarter. They rush to see through the window where the camera shows us his wife, struggling with high fever and gasping for breath in a dimly lit, claustrophobic room. Aparna asks Asim, “Did you know she was so sick?”

The chowkidar’s character becomes a conduit here to foreground the moral ambivalence of Ray’s middle-class protagonists. When seen through the eyes of Aparna and Asim, he is merely a pitiful figure.

The caricaturised Santhal girl

Simi Garewal played the pivotal role of the tribal girl Duli. The popular fair skinned actor wore black body paint to “become” the Santhal woman. Her website mentions: “I relished my transformation. It took four hours to cover me with the black paint (even in my ears!) – and it took three hours to remove it later! And in-between I became another being, rustic, inhibited, untutored and raw.”

Simi Garewal as tribal girl Duli. Photo arranged by author.

The first time we see Duli, she is shown drinking in the liquor shop. In a state of inebriation, she comes closer to the four men and asks for an adha pauwa (half–pint) drink. Hari is immediately attracted to her. Duli is clad in a white saree, with tribal jewelry on her ears and neck and flowers in her hair.

At the onset of the film, Sanjoy reads from Sanjib Chandra Chattopadhayay’s description of tribal women in his travel account titled Palamau, written arounds 1880: “They are as black as ebony, and young. Dressed only with a piece of cloth around the waist, their upper body remains naked.”

Ironically, almost after ninety years, in Ray’s cinematic world, the exoticised representation of marginalised women reaches for the same stereotype. Duli’s mannerisms, the way she moves and speaks are nothing short of an urban middle-class fantasy version of Adivasi women.

Also read: Satyajit Ray: When the Filmmaker Dons His Critic Hat

Later in the film, Duli and two other women come to the rest house in search of work. When Duli starts cleaning the room, the camera voyeuristically gazes upon her body. Towards the end, Hari is shown seducing her, offering sexual intercourse in exchange for money. It is made evident that Duli’s body becomes a vent for Hari’s frustrations from an earlier rejection by his girlfriend back in the city.

Duli is portrayed as submissive and naïve, stereotyped and exoticised. In a recent article, Maroona Murmu, an Adivasi university professor, writes about how these stereotypes persist belligerently in the Bengali upper caste imagination: “A colleague once told me that I did not look like a typical Santhal. On being asked how a typical Santhal should look, the colleague offered a description that more or less matched how Ray had portrayed Duli the Santhal woman in his film Aranyer Din Ratri.”

Lakha’s revenge

The four friends meet Lakha, a local tribal youth on their way to the forest in the opening of the film. He is wearing a tattered sando genji and half pant and smoking a bidi. As Asim promises him baksheesh, Lakha starts running errands for them – from calling the caretaker to visiting the local market.

The men communicate with condescension, each time they speak to Lakha. When he meets them in the liquor shop, a drunk Asim wonders how much money he is pocketing from them. But things escalate further when Hari openly accuses Lakha for stealing his wallet. An aggressive Hari violently tries to search Lakha and beats him up. After the entire incident, Asim hurriedly gives Lakha a token amount and shoos him away.

The moment of revenge: Lakha beating up Hari. Photo arranged by author.

In the climactic sequence of the film, Lakha follows Hari in the forest. On Hari’s way back to the bungalow, Lakha ambushes him with a stick from behind. When he tries to resist, Lakha hits him again. As a bleeding Hari falls semi-unconscious, Lakha snatches his wallet from his pocket and disappears. This violent assertion stands as an aberration in the entire narrative.

Throughout the film, the local villagers are extremely compliant, following the orders of the four men without batting an eyelid. But Lakha’s revenge eventually becomes the heightened moment of rupture.

Aranyer Din Ratri was produced at the height of the Naxalbari movement in West Bengal. It is important to note that May 1967 marks the beginning of this uprising in the northern part of the state, where local peasants militantly fought back the landlords and state police. In Ray’s film, there is no direct reference to the movement that once shook the state, and yet Lakha’s revenge can be read as the cinematic dispersal of the times of rebellion.

In spite of Ray’s critique of the Bengali middle class, characters from the lowest socio-economic strata mostly remain in the margin of his films. They are stereotyped, and often just facilitators in the narrative schema to hint upon the hollowness of the middle class. Aranyer Din Ratri is no exception, except the fleeting moment when Lakha strikes back.

Aranyer Din Ratri re-release poster. Photo arranged by author.

After Aranyer Din Ratri’s global recognition at the Cannes 2025 festival and the re-release, once again, there is euphoria around the film and the auteur’s cherished legacy. The “class” of Ray’s cinematic vision and technical brilliance in the film are nostalgically celebrated in journalistic writings and remembrances. In this moment of celebration, what is forgotten are the other questions of “class”, and the “chotoloks” at the peripheries of the iconic film.

Agnitra Ghosh teaches mass communication and journalism at Jadavpur University, Kolkata.

This article went live on November twelfth, two thousand twenty five, at seven minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.