“There’s a sort of evil out there,” says Sheriff Truman in an episode of David Lynch’s iconic TV series, Twin Peaks.

That line gets to the heart of Lynch’s work, which reflects the dark, ominous, often bizarre underbelly of American culture – one increasingly out of the shadows today.

As someone who teaches film noir, I often think about the ways American cinema serves as a mirror to society.

David Lynch is a master at this, so I was pleased to learn that he’ll finally be receiving an Academy Award for his lifetime service to film on October 27.

Many of Lynch’s films, like 1986’s Blue Velvet and 1997’s Lost Highway, can be unsparing and graphic, with imagery that’s been described as extreme and “all chaos” upon their release.

But beyond these bewildering effects, Lynch was onto something.

His images of corruption, violence and toxic masculinity ring all too familiar in America today.

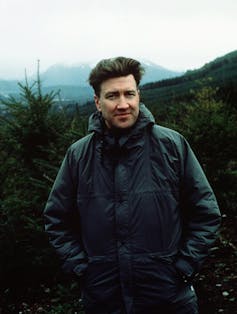

David Lynch in a 1990 photograph.

Take Blue Velvet. The film focuses on a naive college student, Jeffrey Beaumont, whose idyllic life in a suburb filled with white picket fences is turned inside out when he finds a human ear on the side of a road. This grisly discovery pulls him into the orbit of a violent criminal, Frank Booth, and an alluring lounge singer named Dorothy Vallens, whom Booth sadistically torments while holding her child and husband – whose ear, it turns out, was the one Beaumont had found – hostage.

Beaumont nonetheless finds himself perversely attracted to Vallens and descends deeper into the shadowy world lurking beneath his hometown – a world of smoke-filled bars and drug dens frequented by Booth and an array of freakish characters including pimps, addicts and a corrupt cop.

Booth’s haunting line, “Now it’s dark,” serves as an appropriate refrain.

The corruption, perversion and violence shown in Blue Velvet are indeed extreme. But the acts Booth perpetrates also recall the stories of sexual abuse that have emerged from organisations like the Catholic Church and at universities such as Penn State and Michigan State.

As more and more of these crimes come to light, they become less an anomaly and more a warning of something deeply ingrained in our culture.

These evils are sensational and appalling, and there’s an impulse to perceive them as existing outside of our realities, by people who aren’t like us. What Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet do so effectively is tell viewers that those other worlds where venality and cruelty reside can be found just around the corner, in places that we might see but tend to ignore.

And then there are the uncanny and eerie worlds depicted in Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, whose characters seem to live in parallel realities governed by good and evil.

In Lost Highway, David Lynch fuses the worlds of good and evil. Photo: The Movie DB

Lost Highway begins with a man named Fred Madison being convicted of killing his wife. He claims, however, to have no memory of the crime. Exploring the theme of alternate worlds, Lynch then thrusts Madison into an illusory realm inhabited by killers, drug dealers and pornographers by merging his identity into that of another character named Pete Dayton. In doing so, Lynch combines the worlds of “normality” and corruption into one.

In the 1990s, artists like Marilyn Manson, who has a minor role in the final chaotic scenes of Lost Highway, also confronted audiences with imagery of decadence, corruption and social decay. The backlash Manson and his peers received was fierce.

But these dark themes have since been personified in rich and powerful men like Vikram Chatwal, Bill Cosby and Jeffrey Epstein, who, for years, skated along the surface of high society while their perversions were hidden from the public.

In his 2001 film, Mulholland Drive, Lynch turns his attention to Hollywood and the rot that seems baked into its very nature.

A wide-eyed and innocent aspiring actress named Betty Elms arrives in Los Angeles with visions of stardom. Her struggle to achieve success – one that ends in depression and death – is certainly tragic. But it’s also not very surprising given that she was trying to make it in a corrupt system that all too often bestows its rewards on the undeserving or those who are willing to compromise their morals.

As with so many others who go to Hollywood with big dreams only to find that fame is beyond their reach, Elms is unprepared for an industry so consumed with exploitation and corruption. Her fate mimics that of the women who, desperate for stardom, ended up falling into the trap set by Harvey Weinstein.

So it seems fitting that as David Lynch prepares to accept his Academy Award, America continues to hurtle towards an ever darker future. Perhaps it’s one foretold by a present in which politicians can turn a deaf ear to acts of sexual assault, while tolerating the vilification of victims – or even brag that they can get away with murder.

Lynch’s body of work implies that the cruelty of such people isn’t really what we should fear most. It is, instead, those who laugh, cheer or simply turn away – responses that enable and empower such behaviors, while giving them an acceptable place in the world.

When they were first released, Lynch’s films may well have appeared as funhouse mirror reflections of society.

Not so anymore.

Billy J. Stratton, Professor of American Literature and Culture; Native American Studies, University of Denver

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.