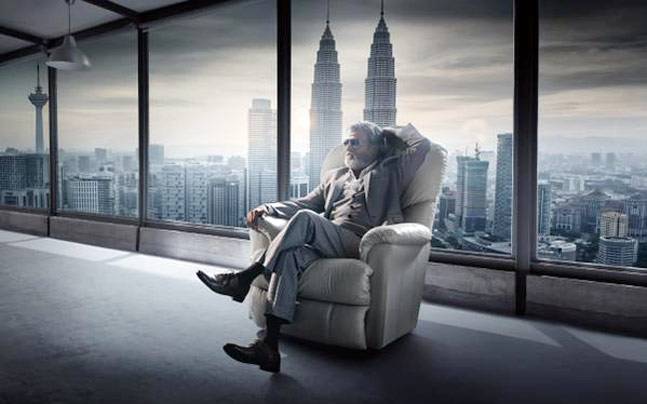

Kabali is a Shoddy Film With Old Rajinikanth Tricks That Don't Work Anymore

Superstars in films are like children in amusement parks. They’re expected to not play by the rules, to break them at will. They’re allowed their indulgence and enthusiasm. They don’t necessarily have to make sense or pretend to be smart. Superstars are just expected to be themselves. No other profession rewards so much by expecting so little.

The fact that an Indian superstar enjoys his excesses on screen is undisputed, but the real question is, to what extent? To what extent can a superstar get away with mediocrity? To what extent is he supposed to take his audience for granted, test the limits of their devotion? To what extent can he lower the bar of stardom? A terrible film headlined by a superstar, which becomes a blockbuster, says less about him and more about the movie-watching audience, about the lack of choices we’ve foisted on ourselves, about our refusal to see or expect anything new. Rajinikanth’s Kabali isn’t a blockbuster yet, but if it does become one (which, to be honest, doesn’t look far-fetched), then the actor’s fans must really think hard about their devotion, and where that is taking their beloved star.

In his latest, Rajinikanth plays the eponymous gangster Kabali who’s been released from a Kuala Lumpur jail after 25 years. Since Rajinikanth is playing a gangster, the filmmaker, Pa. Ranjith, feels compelled to qualify him. Kabali, we soon understand, isn’t just a regular gangster. Unlike the members of Gang 43 (his rivals), Kabali doesn’t trade in drugs or women. Like in most mainstream Indian films, here, too, the hero is a gun-toting saint. Not only that, Kabali is a star in Kabali. When he is released from jail, the other inmates burst into a rapturous applause. He’s supporting Free Life Foundation, an organisation that rehabilitates drug addicts. Less than five minutes after he is released from jail, he storms into the house of his rivals, beating them to pulp, announcing his arrival. And a little later in the film, with only a hint of provocation, he drives his car over another Gang 43 member. No one questions the plausibility of these scenes, because such films have an unwritten contract with the audience, where they enjoy the whims of their badass star, without thinking too much about smarts or logic. But the main problem with Kabali is that it’s so devoid of humour, and any shred of self-awareness, that after a point you’re laughing at the film, not with it.

Quite early in the film, a young girl at the Free Life Foundation calls Kabali, “Papa.” It’s a clever in-joke, to begin with, given that Rajinikanth hardly plays a character of his age on screen, and he’s broken that norm with this film. But instead of smartly playing with the joke, Rajinikanth, in the next scene, with a deadpan expression, merely strokes his chin and says, “That girl called me papa”, in a small moment that qualifies to be a masterclass in bad acting. I watched the dubbed version of Kabali, in Hindi, but I doubt that scene would have been anything other than embarrassing in Tamil, too. And this continues throughout the film. The dialogues dubbed in Hindi are so bad that you aren’t sure if the makers are playing an elaborate prank on the audiences or if they’re being plain inept.

By the film’s first half, you’re convinced that it’s the latter. At one point, Kabali is contemplating adopting that girl (because that’s the only option left when a stranger calls you “Papa” more than a few times): “Jab bhi woh ladki ko dekhta hun toh mere andar jazbaat ki lehar daudne lagti hai (whenever I see that girl, I become overwhelmed with emotions).” Go back to being young, Rajini, you want to say, but then, sure enough, no one’s listening. When Kabali calls out a local businessman for being racist, and ends his monologue with, “If you think I’m threatening you, then I am”, there’s a moment of tense silence before Rupa (Radhika Apte), Kabali’s wife, punctures that moment with “Yay” as if she’s mistakenly walked into a different film set.

Goes on and on

The film goes on and on and on in a similar fashion, with awful dialogues and acting that ranges from passable (Apte) to sloppy (Rajinikanth) to terrible (rest of the cast). Forget that the film has a pedestrian plot (which is fine, a star can still transform weak writing to something enjoyable), but what’s worse, in Kabali, the subplots are fashioned and stretched to appease a star’s vanity. There’s an entire subplot involving Kabali and Rupa in Tamil Nadu, which seems to be in place just so that the audience can see their star romance on screen.

Kabali could have been bearable had it been a film with Rajinikanth in his element; here, he looks like a washed-up star, who is desperately trying to conjure up old tricks, but nothing seems to work. The film’s also incredibly juvenile, where companionships, filial love, and rivalries are played out like the imaginations of a twelve-year-old. To be precise: a twelve-year-old who has no future in writing. It’s sad that a film this shoddy, with not one redeemable quality, has managed to hit the screens, has managed to create this much frenzy. But maybe it’s wrong to be surprised. Maybe that’s the cost we pay when we stop questioning our stars. Last year, it was Shahrukh Khan’s Dilwale, which stretched the limits of how bad a film helmed by a star can be, and this year it’s Kabali (which, to the horror of horrors, makes even Dilwale look better).

American filmmaker Howard Hawks believed that a “great film has three good scenes” and no “bad scenes”. I don’t know what you’d call a film that has not one good scene and at least a dozen terrible scenes. I don’t know. I don’t want to know.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.