‘For the First Time, Palestinians Are Winning the Narrative and Image War’: Filmmaker Mai Masri

The Palestinian filmmaker, Mai Masri, was in Delhi last month to attend a film festival organised by the Indian Association of Women in Radio and Television (IAWRT). Her wonderful, warm and heart-breaking documentary, Frontiers of Dreams and Fears, about friendships between Palestinian children in refugee camps in Beirut and Bethlehem, was one of the highlights of the festival. Two other films by Masri – Children of Shatila and 3,000 Nights are available on Netflix. The first is a documentary that follows a boy and girl in Beirut’s infamous refugee camp of Shatila. The other is a work of fiction about a young Palestinian woman who is sentenced to prison, where she discovers she’s pregnant.

On stage, Masri cut a striking figure, courageous and impassioned. Closer up, she also revealed herself to be generous and funny, as Parvati Sharma and Shahrukh Alam discovered in the course of a conversation. Below is an edited excerpt from the interview:

Shahrukh Alam (SA): In your film yesterday [Frontiers of Dreams and Fears], there was this scene that I was struck by where the children are using the sling…

Mai Masri (MM): The slingshot.

SA: The slingshot. It reminded me of [the Biblical] David’s slingshot and his throwing of the stone [at Goliath]. Do you think this is cultural appropriation? Are the Palestinian children appropriating David’s methods?

MM: No, you know why? Ancient history is in Palestine through thousands of years! Slingshots are older than David; they were probably using slingshots in the time of the cavemen.

SA: Yes. This was [a] joke.

[Both laugh]

SA: I was trying to be like Philomena Cunk [the satirical presenter played by Diane Morgan]?

MA: You were pulling my leg! Why didn’t you tell me, you looked so serious. I’m probably related to David anyway, there’s more Semitic DNA in Palestinians than in Ashkenazi Jews!

Parvati Sharma (PS): But that was a good opening, because it’s also about the inversion of power right? It’s the person throwing the stone who is declared the terrorist and the person wielding the gun who is declared the peacekeeper. And in your films this plays out again and again. Like in 3000 Nights, when the prisoners are banging their cups [in protest] and the guard’s bullet that sings out. Or how you ended up making films with and about children, which is also the most vulnerable category of people in this whole situation…

MM: Well, I liked the idea [of working with children] in general. I went to Palestine during the first uprising, the Intifada. I was unable to enter, in the beginning, my hometown Nablus, because the uprising was ongoing and Nablus was a hub for resistance. It’s also known as the Mountain of Fire – Nablus – because it has always resisted foreign occupation: Napoleon, the British, then the Israeli occupation. And it was my first time in Palestine as an adult. I had the camera and the small crew with me and it was almost impossible to enter the city because it was a closed military zone.

Finally, we were able to go in through the back roads and by a miracle we ended up in Nablus, the only camera in the town with soldiers everywhere, [and] fire, stones, bullets…

Also read: The Art World Is Succumbing to the Pressure of Ostracising Those Who Support Palestine

I discovered I have lots of relatives, cousins, hundreds of them, they all live in one neighbourhood so they took me in and I was in an apartment filming secretly from the windows. I was worried, “What am I going to do?” Everything I had planned was impossible. [Then] I understood the film was about that, being under curfew, under siege, filming secretly from the windows. I became the main character.

There were children in the building – it was small, four storeys – and I started filming them. I chose two: a 5-year-old boy and an 11-year-old girl and told the story through their eyes. It made me connect to my town and my people. “Palestine” for me became related to real people, a real place, not just a dream. And I discovered the magic of working with children. They are so natural, so spontaneous, so open and honest and childlike at the same time.

'Children of Shatila'. Mai and the children with a camera. Photo: By arrangement.

PS: What is also hypnotising about these kids and most tragic is how they combine in themselves this unformed, childlike quality plus this terrible world-weariness. In Children of Shatila there is little Isa talking about how he’s fed up with everybody and how he’s tired of life and he’s tired of himself. You don’t imagine a child [talking like that]. I wanted to ask you about that. And I was curious to know about your own childhood, too.

MM: I made three films with Palestinian children and really wanted to see through their eyes. Each film takes a different shape. In Children of Shatila, I actually gave them the camera. I chose two children again: Isa, whose story is very special, he’s not a typical kid, and Farah who’s very bright and talkative. Isa is very quiet and slow because he had an accident and he lost his memory and that is very symbolic because he’s trying to reconstruct his life and remember. It was like a window to reality because Palestinian connection with memory is very special, too, especially for the Palestinians who were expelled from Palestine, the hundreds of thousands who ended up in refugee camps. Memory is transmitted from generation to generation, oral history.

There are different layers – there’s a childlike layer, there’s a worldliness, like you said. They’re all very mature and it’s very surprising how they understand their reality. Because they’re forced to, they are street wise, these are kids who have lived through really traumatic experiences and when they talk, they say, “My uncle, my mother, my aunt were all killed…” It’s very common. Especially in Shatila camp, which has been through a lot of invasions, massacres. It’s known for the Sabra and Shatila massacre [1982], the War of the Camps [1985], so every single person has been touched by that.

I am also one of the Palestinians who were in the diaspora. I was lucky not to be raised in a camp, although I think, in the case of Farah and Isa, it plays an important role in [forming an identity], being together in a camp. The community is tight knit, they hold on to their accent, their habits. Many of them come from the same villages, so it has an advantage even though it’s a very difficult life.

I was raised not far from Shatila and growing up I was seeing it being bombed by Israeli fighter jets, F16s. Now we’re up to F35s already – you start to understand the weapons [laughs]. I remember feeling very angry.

My childhood was influenced by the political atmosphere – but I was not impoverished at all, I had access to a good school and met many people active in the student movement.

Then, the war in Lebanon broke out in 1975, when I was 16, [and] thinking what am I going to do with my life. I was lucky to choose cinema. It was really perfect because it combined so many things: the art, the visual and the storytelling. Film is a powerful tool of communication for the Palestinians because we want to have a way to speak out.

PS: You’re talking about telling the story of Palestinian people and having a narrative to challenge the whole machinery of propaganda. It is relatively easier to produce counter-narratives now, but, at the same time, is it also more difficult to reach people who don’t want to listen?

MM: I don’t think it’s more difficult. I think it’s easier now with social media to reach a lot of people. With social media and video cameras, people have access to information. Before, they only had the mainstream information. Now, information is available and many young people are changing their mentality. I was in the United States in November and I was very, very impressed to see many young, Jewish students and young professionals, how active they are for Palestine. They are watching, they are influenced by the counter media, by Youtube and TikTok.. If they didn’t have that, it would be difficult for them to know what’s going on.

PS: You’ve seen people change their minds?

MM: I’ve seen! They’re called the Jewish Voice for Peace and there are others like them – many anti-Zionist Jews, intellectuals and academics, it’s quite phenomenal. Outspoken people – many people who are losing their jobs, you know. I didn’t see that before. In Hollywood, people like Susan Sarandon, Mark Ruffalo and others are speaking out. It was very rare [in earlier decades]. Jane Fonda, who was the hero in Vietnam [for speaking out against the Vietnam War], [even] she came to Lebanon to entertain Israeli soldiers in 1982. It’s hard to defend Israel now – it’s very hard. Even Biden, I think, is having trouble defending Israel. The Palestinians are, for the first time, winning the war of the narrative and the war of the image.

Also read: 'Not in Our Name': The Jews Who Refuse to Be Bystanders to Historic Injustice

SA: You said that in Nablus, when you were filming and hiding, you realised that that’s what filmmaking is: doing things in the teeth of power, with physical danger to yourself. How do you differentiate – you know it instinctively, but how do you teach someone what is propaganda and what is truth? We have a situation here when power is investing very heavily in the arts. You have a film on every issue that agitates people and they are very slick films. How do you distinguish propaganda from art – that’s very subjective as well, right?

MM: I would [say], read. Read, read, read. Inform yourself. Read different opinions. And then go there to Palestine and use your eyes. Even if you don’t read a word, you see the Wall and you see those soldiers. Even if you don’t go, you look at the images coming out of Gaza from Palestinians themselves, from Palestinian journalists who are being killed like flies every day. You will see that those images are going to remind you of World War II; they’re going to remind you of the Holocaust even. When you see naked people, in their underwear, being rounded up like animals, mistreated like that. When you see the destruction.

SA: But that’s the thing about images, Mai. There are images galore but they are [also often] staged.

MM: Yeah, so it’s a struggle. It’s not easy. I’m not saying it’s over, we won, no. They are continuing the genocide and the ethnic cleansing. There are all kinds of devious plans, everything they plan is devious and I’m not just talking about Israelis. I’m talking about their friends. The Americans, the Europeans, they are all devious. They talk about sending food by air, parachuting the food. Do you know, five people were killed by those boxes of food? Can you believe it [a Guardian report mentions a witness saying that a Gaza aid airdrop ended up killing civilians as the parachute failed to open]?

It’s a big responsibility really, how to talk about your reality. An artist is not objective. There’s no such thing as objective in anything, especially not in art – but you try to be fair and honest with your point of view.

'3000 Nights'. Layal and Nour at the window. Photo: By arrangement.

PS: The idea of solidarity between people: in 3000 Nights, you have this scene of confrontation between the Jewish lawyer [defending the Palestinian convict] and the Jewish jailor. There’s a faceoff between them and the lawyer says “Have you forgotten your own history?” And right at the end, she’s in the frame when the protagonist is released. How important are solidarities like these between Israelis and Palestinians, and how possible are they now?

SA: These children [in Frontiers of Dreams and Fears], for instance, will they ever have opportunities to make Jewish friends?

MM: Yes! But [right now] there’s not that much mixing going on. There is segregation, there’s apartheid – it’s like asking in South Africa whether the blacks had white friends.

SA: You’ve expressed your anger and disappointment with the west, but it’s the western states versus their people who are out on the streets. How do you begin to think about global solidarities?

MM: I’ll start with [Parvati’s] part. I dream of a time when there would be more communication between the Palestinians and the Israeli Jews. Understanding each other is an important step. But right now, there’s an occupation and a genocide going on and unfortunately a huge majority of Israelis support it. They are not at all upset with the Israeli army killing Palestinians; they think the civilians are just as bad as the fighters. It’s become very aggressive.

Before, in the 1980s, during the Israeli invasion and siege in Beirut, there was more solidarity. There were demonstrations. After the Sabra and Shatila Massacre, there were 300,000 or 400,000 Israelis demonstrating against their own government. It was more “Bring our soldiers back home”, but at least there was a left movement, a so-called progressive movement. But now, it’s disappeared. Most of the intellectuals have run away or are quiet. I’m talking about Jewish intellectuals, professors, top people like Ilan Pappé, Avi Shlaim, people who are teaching in important universities outside but are not well received by Israel.

In an ideal world, we do need the Israeli Jews to change their position. This change has to come from within. Like in South Africa when they understood, the white supremacists, that the game was over, that they have to share the land, that’s what they did. That’s what has to happen in our case as well. There’s no other way whatsoever.

For international solidarity – of course, I think the vast majority of public opinion is on the Palestinian side.

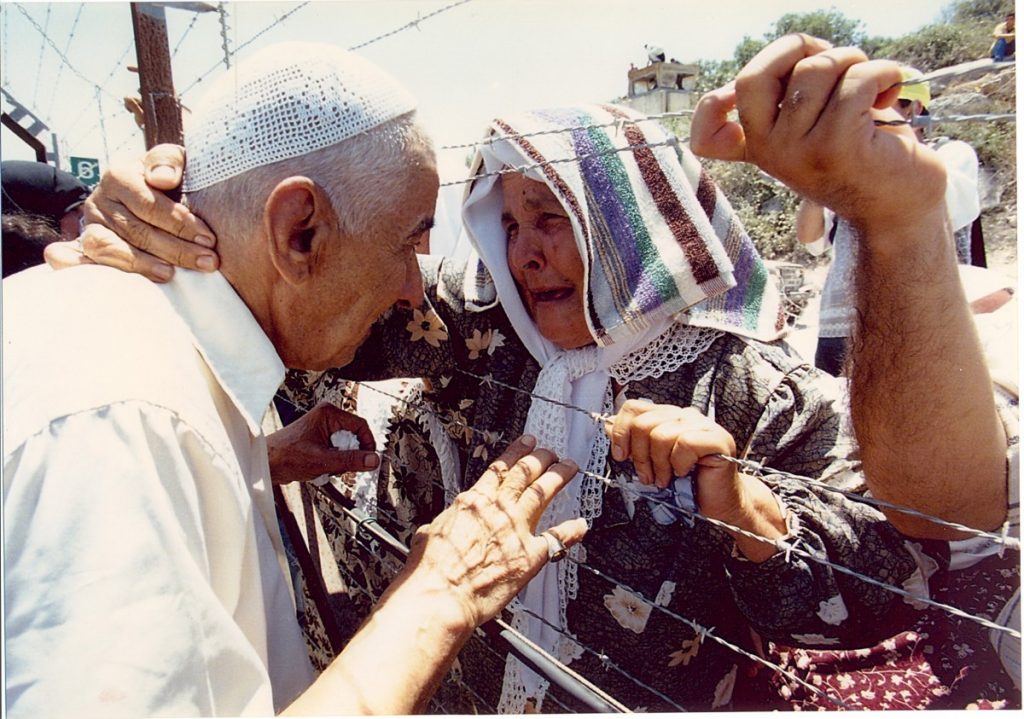

'Frontiers of Dreams and Fears'. Brother and sister meet for the first time in 52 years. Photo: By arrangement.

SA: And they’re not all Muslim, right?

MM: No of course not! It’s nothing to do with Muslims. South Africa is not Muslim. Latin America, where the most support is coming from – none of them are Muslim. India used to be the biggest supporter of Palestine. And I hope that India will play that role because it’s such an important country, it’s a continent. I think [Indians] understand what it is to be occupied because we were both occupied by the British. In 1947, India received its independence and we lost our country. So I think that they can identify with that.

Governments are not representing their people in the west. Even in the United States, even within the Democratic party, people are against the war. They want a ceasefire.

SA: And the Arab states?

MM: The Palestinian people feel abandoned by the Arab governments and they are shocked that they haven’t taken a stronger position. The people, of course, support the Palestinians but they have been silenced and terrorised for many reasons. There is support and there are open battlefields, like in Yemen, in Southern Lebanon, in Iraq, in Syria. But the Arab countries can do much more. If they put their foot down, it would make a big difference. They have the power to put pressure.

SA: I think you implied that you would want a united Israel-Palestine, not a two-state solution?

MM: Yes. Because that’s the only solution. The Israeli government has made it impossible to have a two- state solution because of the settlements and the appropriation of land. They broke every single agreement they signed, every single UN convention.

I want one state. I believe that this is the way forward. It’s the best solution for Palestinians and Israelis, because the Israelis need to liberate themselves from a racist, fascist ideology. It is not sustainable in the long run.

All occupiers always lose. In our countries, we come from very long histories and cultures; we count the years by the hundreds and thousands. They’ve been around for, what, 75 years? That’s nothing in history. Things will change. The Crusaders spent 300 years in Palestine, the Holy Land, but in the end they were defeated. And many of them melted into the population, that’s why you have a mix. Palestine [is a] melting pot of all the occupiers who have passed through. But the Palestinians stay; we are the people of the land.

They come and go, but we stay.

SA: Is that the common conception? How Palestinians think of themselves ethnically?

MM: I’m not sure, but it is historically correct.

SA: Historically yes, but they are portrayed as Muslims…

MM: Yeah, I know: “It all started with the Arab conquest.” But there’s thousands of years before that.

SA: In 3000 Nights, the scene of [the protagonist Layal’s] arrest reminded me of this movement in Palestine: “Smile when you’re arrested”. There were these beautiful videos of children and young women being arrested and dragged and smiling into the camera. That was powerful but also a contrast with your film, in which there is physical fear. Layal is crying and bloodied. I was thinking about the power of this movement, resisting with simple dignity, and I had two questions. Even in the film, she is shivering in fear in one moment and then she finds anger within her and pushes back, even pushes back the guard, and she finds dignity within her. Where do you think that came from? And what is your relationship with humour as an individual and as an artist?

MM: Now don’t ask me a third question, my mind doesn’t work like that! In a film or any story, it is important to follow an arc, a journey. You don’t start with the end. People are not born heroes, not even Palestinians [laughs]. They’re forced to [become so] for survival, you have to be strong. Life and resistance makes you a stronger person. So, with Layal, I wanted her to be an ordinary person, I wanted her to be not a militant but someone who is not political, who becomes so through her connection with other prisoners, becoming a mother. Who finds the strength to stand up for herself. I wanted to show her as very afraid, and I think many people would be afraid.

Smiling is a political stance. Normally you wouldn’t smile if you were being arrested. It was admirable that these young people, especially in Jerusalem, were smiling as they were being arrested. They are making a statement. Or in court, their hands are chained but they’re making gestures of defiance and resistance. Now it’s more scary than ever [for] anyone [who is] arrested, a lot are dying in Israeli prisons, being tortured; being disappeared in Gaza. There is rape and sexual harassment, documented by the United Nations. But the world does not [see]; they’re trying to concoct a lie on the other side, but [even] with real proof there’s no action, and the women’s movement is not doing anything about it.

About humour: I think that’s a very powerful weapon. I never thought I was funny or had much of a sense of humour. But with age [laughs], and I think community, because I have a lot of women friends, mostly women friends – they are more fun really, they’re more interesting. The older they get, they reinvent themselves and they become much more interesting. Men, I don’t know! So we laugh a lot. And living in a war zone, you have to have humour to process what’s going on. It strengthens you when you can laugh at reality. Under occupation, you really have to have humour and sarcasm and use all those weapons. So in my writing, now, as a filmmaker, I’m surprised that I’m writing humour. I never did, before, but now it’s important to tap into something that exists and is real and to use it in your art.

Mai and Jean Chamoun in 1986. Photo: By arrangement.

PS: If I’ve understood correctly, in your body of work, you’ve explicitly had the idea of making your work in order to change things…

MM: Yeah, not really in the beginning. I wanted to do something that I felt passionate about, but I discovered that films could change people’s minds and also inspire them to take action. But I didn’t sit there saying, “I’m going to make this film because I want to create change”.

PS: But your films have impacted people, their focus is on highlighting injustice and creating a counter-narrative, and, at the same time, they are beautiful and moving works of art – and the two don’t always go together. How are these linked in your mind: art and activism?

MM: I think, for me, it comes naturally, because I have that in me, the artistic and storytelling – I love them, I always have -- and I have the political side, too, so it’s just combining those two, together. And feeling connected to your people.

Forget the word politics, [it’s] just empathising and understanding your people, and them trusting you and believing in what you are doing. It’s fighting injustice and telling your people’s story. There’s a whole attempt to erase the Palestinians and destroy their memory in history so this is also safeguarding memory for generations.

But I just want to tell you a little story about someone I met yesterday, a volunteer with the [IAWRT] festival. She wanted to speak to me after the film and we sat together. And she said, “I wanted to tell you my story because I felt so connected to the film, I felt as if Mona, [one of the children] in the film, was speaking for me.”

She said that her father had an accident and he couldn’t support the family and she had to work when she was a child and her brother, too, and her mother had to work as a maid. She’s still working to support her family, as she’s studying. And she felt the film was representing her. So that was an example of how people can be touched – not on a political level, on a human level.

SA: Is there a legal category of the political prisoner in Palestine?

MM: Not for the Israelis, they call them “security prisoners”. They are not political in their eyes.

But for us, the Palestinian prisoners are political prisoners.

PS: Right now, you’ve said that you have more hope [than usual].

MM: Hope is the most dangerous thing by the way. In Frontiers of Dreams and Fears, when people [from the Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut] were going to Southern Lebanon to see the border and look at Palestine for the first time, and to see their relatives, that gave them hope. And that is so subversive, having hope. So the Israelis have been trying to destroy the concept of hope in the Palestinians.

SA: Do you mean hope in historical time or immediate hope?

MM: I have immediate hope.

SA: Why?

MM: Why? Because my people are resisting. When you resist you are no longer a victim. And the world is looking now at Palestine and being inspired because they’re resisting, not because they’re victims.

SA: And what distinguishes a victim from a resister?

MM: The difference is hope. The victim usually doesn’t have hope – it’s destroyed, defeated. When you resist, you have hope. [Laughs] You’re making me say big statements! I [don’t] usually – it’s not really me. What I’m saying, speaking, it’s coming out of me, I’m the vehicle, I’m possessed. I can’t help it, I’m angry – not angry, “angry” is an ugly word. I’m inspired, I’m fired up.

PS: Do you think there will be change in the global world order also?

MM: In the global world order, I hope so! It’s time to change, you know? How long can people be oppressed and suffer? It’s now or never.

Parvati Sharma is an author. Shahrukh Alam is a lawyer.

This article went live on April seventh, two thousand twenty four, at twenty-three minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.