Kolkata: A middle-aged man sits on a low stool in front of his house in Tarakeswar in a narrow alley.

The morning light shines through a thick fog. He starts putting make-up on his face while Bengali folk music plays in the background. His children gather around him. A few seconds later, his daughter takes the make-up brush and starts painting her father’s face after which he starts dressing. He puts on two false hands, a false tongue sticking out of his mouth and slowly, transforms into the Hindu goddess Kali.

Tarakeswar is a small town in West Bengal around 60 km northwest of Kolkata known for its Taraknath temple and a vibrant but dying community of bohurupis who are performing artistes who dress up as figures, mostly mythological.

The man in question is Ravi Pandit, a revered bohurupi from West Bengal and one of the subjects of filmmaker, thespian and playwright Rajaditya Banerjee’s new documentary, Dying Art of the Bahurupis of Bengal which looks into the almost extinct art of polymorphism – the ability to take on many forms – and the lives of the polymorphic artistes of the state.

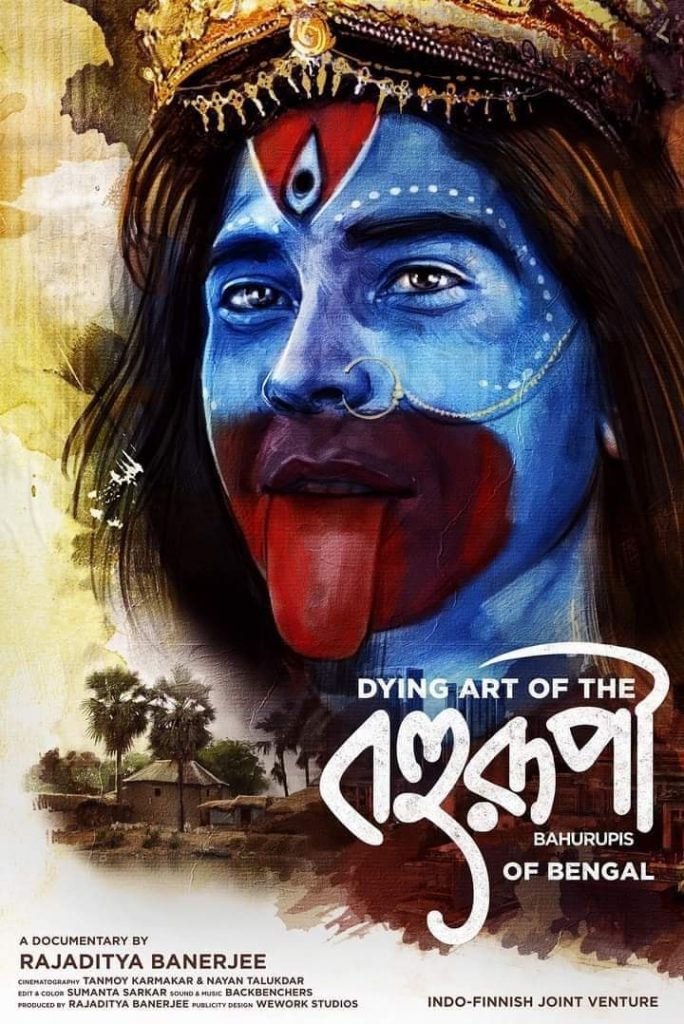

The poster for Dying Art of the Bahurupis of Bengal

Banerjee, who earlier made Death Certificate, brings forth in his latest film the challenges in the lives of the polymorphic artistes at a time of increased consumption of fast and cheap entertainment through the internet.

“If the young generation of people do not take up this form, the entire tradition of bohurupis will wipe away. But how will they? They do not relate to the art form. Those who do, don’t earn enough. If something isn’t done soon, Bengal will lose a unique art form,” Banerjee said.

Also read: In Photos: The Fading Tradition of Hand Block Printing in Rajasthan

Banerjee’s fascination with bohurupis

Bohurupis, the name they are known by in Bengal, practice a traditional performance art unique to the eastern states of India and known by various names.

“The reason why I chose to make this film is because I witnessed a decline in the numbers of bohurupi artistes in the state,” Banerjee said.

Banerjee’s father, Debashish Bandopadhyay was a famous litterateur, film-maker and editor of Bengali children’s periodical Anandamela Patrika. He built a folk and tribal museum full of artefacts in the house Banerjee grew up in. Bandopadhyay also wrote books on Bengal’s culture. That’s where the filmmaker first learned about bohurupi neighbourhoods, like Shitalgram in Birbhum and their culture, which piqued his interest.

Banerjee directing one of the bohurupi artistes performing in his film. Photo: Rajaditya Banerjee.

“I was always interested in making a film on the artistes but due to work and tight finances, I couldn’t address the topic till now. While shooting for Death Certificate and other films in several districts of Bengal, including Birbhum, Bankura, Murshidabad, Hooghly, Purulia and the like, I witnessed a huge decline in the numbers of bohurupis,” Banerjee said.

Also read: COVID-19: With No Financial Support from Govt, Performing Artistes Left High and Dry

“In Birbhum district’s Shantiniketan, a famous tourist spot is the haat (local market) next to the Khoai river. One would see bohurupis performing in the haat but now their numbers have dwindled.“

His worries are reflected in the film where he follows and interviews multiple artistes, ranging from young teens like Rajesh Barman to legendary award-winning bohurupi Subaldas Bairagya, who once performed in Washington for then US President Ronald Reagan at the invitation of Rajiv Gandhi.

The precarity of the lives of these artistes comes through in the movie, along with a nostalgia for a time when the art form was admired and respected.

Historically, these bohurupis would dress up as Hindu gods or mythical characters like Ram, Shiva, Kali, and so on and perform in front of Kings and zamindars.

“There is no documented history of bohurupis in West Bengal. We do not know exactly when this performance art started. It was mainly started to entertain kings as a community profession,” said Rajat Kanti Sur, a researcher in history associated with the Calcutta Research Group. Sur mainly studies the history and politics of performance artistes like the shangs in Kolkata or the nautankis in Bihar.

“We, however, see some evidence of bohurupis in Kolkata from the 1830s. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist before that,” Sur continued.

While researching for his film, Banerjee realised that the cause of this extinction is mainly the unwillingness of the younger generation to pick up the art form, often informed by their poverty.

“In a post-globalised India, people are too exposed to the internet which provides cheap and fast entertainment. This has taken a toll on the traditional art form. The young generation cannot relate to this. Their parents and grandparents might have been bohurupis and some are still performing the art, but the younger generation cannot relate. They do not understand why they need to go and beg in trains or various fairs, walk for miles as mythical characters like Ram, Kali, Shiva,” he said.

Economic hardships have made the craft no longer viable

But many jaat bohurupis (generational artistes) don’t want their children to pick up the art form. Rajendra Byadh from Birbhum’s Bishaypur village is encouraging his children to go to school, study and take up different kinds of jobs.

“Poverty forced us to lead this life. Now poverty is again forcing us to send our children to schools so that they can pursue a different career,” Byadh says in the film.

Most of the bohurupis interviewed in the film come from a low socio-economic background. Pandit, while narrating his life story in the film, recounts how, as a young man from a poor family earning Rs 200 a day by performing as mythical characters made his parents happy. The scenario is completely different now. He has to work as a van driver and a mason to support his family, resulting in the separation of art and livelihood which, initially, were one and the same.

The film also captures some vibrant live performances, solo acts and group acts which are gradually becoming rare because most of bohurupis are now forced to perform as characters that are not familiar to them. Sur says that religion was always closely related to their performances. As bohurupis perform mostly solo acts and their main goal is to earn money, dressing up as Hindu religious characters is helpful. If someone dresses up as Shiva and stands or performs in a market, people won’t chase them away as easily. Instead, they will give them some money.

Traditionally, bohurupies dressed up and performed as various Hindu deities. Photo: Rajaditya Banerjee.

“If you look carefully you will see bohurupis mainly performing during religious festivals like Kali Pujo or near temples like Kalighat, Dakshineswar, Tarapith or Tarakeswar,” Sur continues. “But nowadays, we see bohurupis performing in weddings to entertain guests. Here, however, they mostly dress up as Charlie Chaplin or Mahatma Gandhi. Colloquially, these characters are called ‘cartoons’. So bohurupis are now performing as cartoon characters.”

In the film, Banerjee interviews Nitai Malik, who was trained by legendary artiste Kalipada Pal Bohurupi. Malik is now forced to perform ‘cartoons’, as is Birbhum’s Uttam Mondol.

Also read: West Bengal: No End to Patua Artists’ Financial Woes As COVID-19 Rages

The precarity of the situation is resulting in widespread frustration within the bohurupi community. “Now the artistes are frustrated and turning to alcoholism. Even kids are taking up drugs. You will see many kids at the station doing drugs.” Banerjee says. His film even shows a young bohurupi girl turning to drugs due to frustration and poverty.

Artistes are fighting to keep the tradition alive

Despite the bleak scenario, some people are trying to keep the bohurupi tradition alive, like the sons of Bairagya, Byadh, Pandit and Bhanu Bohurupi. “But for how long? They are also getting old. If the young generation doesn’t come forward and revive the dying art, then a whole chapter of Bengal’s tradition will be wiped away,” the filmmaker laments.

Bairagya, who inspired the filmmaker with his love and respect for the art of bohurupis, tried to open an academy for them where future artistes would be trained, but he did not get the funds from the government and his dream of consolidating the art and artistes never materialised. The septuagenarian now takes comfort in the fact that his son and grandchildren are continuing the tradition.

There are some civil society initiatives that help bohurupis, but they are not overarching. For example, when Kamal Mete, who plays at the Srijani village near Shantiniketan, lost his daughter due to kidney failure, some civil society members helped him. But there is no coalition of such artistes. The lack of solidarity among them due to the scarcity of resources also results in jealousy, competition and alienation, as explained by Banerjee.

The West Bengal government gives a Rs 1,000 allowance to bohurupis every month, but there is a cloud on how many of them get it.

Banerjee too found that arranging for funds to pay bohurupis was a challenge.

“These kind of topics hardly interest producers. I have a theatre group in Finland and we had to collect money by doing shows and also by using the royalties I earned by writing plays,” Banerjee said.

The director sits with his cast of bohurupi performers. Photo: Rajaditya Banerjee.

Apart from the financial challenges, the team also faced obstruction from artistes themselves, who were initially very sceptical and did not want to give the filmmaker access, since many people come from cities to work with them or research on them without providing any recognition or causing any material improvement to their lives. It took the team two-and-a-half years to get an interview with Bairagya, for instanec.

“I remember once, we asked one artiste to show us the certificates he got for his performances. Suddenly, rumours spread that we are trying to steal their certificates and sell them for crores. After a long conversation, they understood that we are not going to misuse them,” Banerjee said. “We are responsible for their scepticism as we have deceived them over the years.”

Banerjee finished the 90-minute film after three years. It talks about poverty, caste questions, sexual orientation, the absence of women performers, children turning to drugs and so on. However, the main thread that binds the film together is the anxiety over the extinction of this unique art form.

Banerjee wants to show the documentary at multiple film festivals in India and across the globe. He also plans to go to villages and rent halls to project it for bohurupi artistes themselves.

“I want to share this film with folk artistes around the world. The challenge faced by them is universal, though it is very acute here in Bengal,” Banerjee said.

Utsa Sarmin is an independent journalist and researcher based in Kolkata.