Lynndie England captured the attention of the world when, in 2004, newspapers and media flashed photographs from one of earth’s darkest places: the Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad. England was caught on camera threatening a naked Iraqi prisoner with a leashed dog, laughing at the humiliated prisoners, etc, and subsequent investigations and evidence revealed her active participation in the torture regime that was Abu Ghraib.

At her trial England pleaded guilty to mistreatment of prisoners, and the media was divided on her role: victim or victimiser. Arguments that she was forced to behave in unspeakable fashion were countered with arguments that she knew exactly what she was doing. Was she scapegoated by both the military and the political bosses for being caught – the debate remains unresolvable.

England’s story is not, however, a unique one.

Before England, and after

Besides cases of women murderers that attract singular attention in the media, the allegedly ‘deviant’ acts of women in situations such as war, genocide and torture have a long history in the 20th century which, naturally, begins at the gates of Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald. Later-day examples of girl-child soldiers now exist in documentation from Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, Sri Lanka and Darfur too. Evidence also shows that the majority of suicide bombers in conflict zones like Chechnya were women, thus situating them as the heart of mass destruction.

Documentary evidence tells us that at least a third of the female population in Germany were a part of Nazi Party organisation. A census from 1945 lists a total of 36,674 male guards and 3,517 female guards from the SS-Gefolge – thus nearly 10% of the guards were female. At Auschwitz, between 1940 and 1945, there were approximately 7,000 male guards and 200 female guards. The secretarial staff in Berlin, nurses at the euthanasia camps (the notorious T4), teachers and workers, besides wives and girlfriends populated Nazi-occupied Europe and kept the Nazi machinery well-oiled during the excesses that occurred. They were not innocent bystanders.

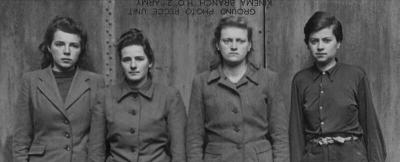

Aktion T4 euthanasia camp. Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Wendy Lower cautions us against assumptions of German women’s absence, or victimhood, in the machinery in her book Hitler’s Furies:

Just as the agency of women in history more generally is under appreciated, here too – and perhaps even more problematically, given the moral and legal implications – the agency of women in the crimes of the Third Reich has not been fully elaborated and explained. Vast numbers of ordinary German women were not victims, and routine forms of female participation in the Holocaust have not yet been disclosed.

Susannah Heschel is categorical in her essay, ‘Does Atrocity have a Gender?’

Although there remains a tenacious belief to this day that women SS guards were not involved in murder, in fact they did participate in the selection of victims and in their murder, as well as in the accompanying torture and brutality. Numerous memoirs attest to the brutality of women guards, including their arbitrary punishment and murder of inmates, and their selection of inmates for gassing.

These are scathing indictments, and history’s jury has its task cut out to determine the exact nature of the women’s role as perpetrators of/in Nazi atrocity. Whether the secretary helped compose memos, transmit orders and enable the planning of atrocities – thereby becoming desktop murderers, as Nazi bureaucrats were called – is open to question. Although their very position within the machinery, and the fact that they benefited from the system, suggests they are, in Michael Rothberg’s definition in the book of the same title, Implicated Subjects.

In contemporary times, women honouring indicted rapists, endorsing genocide or being at the forefront of hate-speech and rabble-rousing if not direct political violence ought to take us back to the gendered nature of mass violence. Then there have been instances of women providing overt and covert support to raping and pillaging men. Finally, there are examples of women exhorting their men to inflict more humiliation and pain on other women.

There are two strands to studies of the gender of atrocity. The first examines how such women as Grese or Koch are represented in history, both in their time and contemporary, so as to throw light on operations of gender in situations of mass violence, genocide and ethnic cleansing. The second studies the contexts in which a certain type of perpetrator emerges from among the women in power.

Beauties, beasts, devils

‘When I laid eyes on Irma Griese, I felt sure that a woman of such beauty could not be cruel. For she was truly a blue-eyed, fair-haired “angel.”’ Thus writes Olga Lenyel in her book Five Chimneys: The Story of Auschwitz. The ‘angel’ and the ‘devil’ slowly merge in such accounts.

The nomenclatural excesses that mark the epithets of Nazi women are indicative of the media and critical-historical construction of them.

Irme Grese, concentration camp guard at Auschwitz and later warden at Bergen-Belsen, was nicknamed ‘The Hyena of Auschwitz’. She was supposed to be particularly sadistic, and is reported to have slept with and/or raped prisoners (Laura Sjoberg, Women as Wartime Rapists). Grese’s sexuality was reported by Olga Lengyel:

The Griese woman was bisexual. My friend, who was her maid, informed me that Irma Griese frequently had “homosexual relationships with inmates and then ordered the victims to the crematory.

And elsewhere:

Irma had seen this splendid specimen of manhood, the handsome Georgian, and, like some Eastern potentate, had picked him for herself. She had ordered him to her room. But when the proud young man, whose spirit had not been broken either by captivity or by Irma’s terrifying reputation, had refused to yield to her wishes, Irma had tried to force him to become her slave by compelling him to look on while she tortured the girl he loved.

Ilse Koch. Photo: Public domain/Wikimedia commons

Ilse Koch, wife of the Buchenwald commandant Karl Koch, was called the ‘beast of Buchenwald’ and sometimes the ‘witch of Buchenwald’. Maria Mandl, famous for creating the Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz that played music during the sorting of Jews – into ‘to be gassed’ and those sent to labour – and during executions, was also called ‘The Beast’.

Hertha Bothe was called the ‘Sadist of Stutthof’. Daniel Patrick Brown titled his study of Irme Grese, The Beautiful Beast – The Life and Crimes of SS-Aufseherin Irma Grese. Deborah Binz, the guard at Ravensbrück, was called a ‘demonic slut’. Carmen Maria Mory was ‘the devil’ of Ravensbrück.

The animal trope employed contrasts with the attention paid to their appearance – beautiful but unrepentant in the court. Animalising the woman perpetrator enabled the legal and media representations to shift them into the realm of the subhuman. Through the use of terms like ‘witch’, ‘devil’ and ‘demon’ the discourse once again bestowed them with nonhuman traits.

Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry in their study of women perpetrators argue that media coverage and reportage, often even legal proceedings, employ three narratives. The women are mothers, monsters or whores:

The mother narrative describes women’s violence as a need to belong, a need to nurture, and a way of taking care of and being loyal to men: motherhood gone awry. The monster narrative eliminates rational behaviour, ideological motivation, and culpability from women engaged in political violence. Instead, they describe violent women as insane, in denial of their femininity, no longer women or human. The whore narrative blames violence on the evils of female sexuality at its most intense or its most vulnerable.

Thomas Jardim’s Ilse Koch on Trial: Making the “Bitch of Buchenwald” also notes that during the SS trial of Koch, her ‘character’ was repeatedly underscored. Jardim writes:

American and German jurists alike … the egregious crimes attributed to Koch were products of a deviant femininity, replete with perverse sexual impulses and a barbarism that placed her outside the community of “ordinary” women

Koch was presented as ‘devoid of “natural” feminine sensibilities. Irma Grese during her trial was the subject of considerable speculation regarding her femininity and sexuality. They were women, writes Jardim, whose ‘crimes were depicted as particularly abhorrent because they clashed with traditional norms of “womanly behavior”. Further, Koch’s supposed role as an active ‘participant’ in the Buchenwald crimes rested on hearsay evidence.

The actions of the Nazi women were amplified as even more abhorrent than that of the hundreds of Nazi men – Karl Otto Koch, Ilse’s husband, was particularly brutal, as evidence shows – because it was unfeminine. They were not ordinary women because no ordinary woman could possibly do what they did. Thus Ilse Koch was supposed to have had prisoners executed so that their skin could be used to make lampshades for her home, which was next to the camp. Such absolute heights of deviant femininity became the stuff of media outrage, as Anthony Rowland notes:

The scandalised narrative of female perpetrators, the fact that (again, invisible) men in the pathology lab might have created the lampshade is of no interest. The perceived perversion of female masculinity allows for a much more convenient explanation of atavism and (male) masculine aberrance.

In other words, attention was focused on the violation of gender norms in situations of political and mass violence. As Alette Smeulers summarises it, ‘women who transgress the female stereotypes more than men do and are therefore more often considered as ‘deviant and unnatural’.

There were other factors too, especially in high-profile trials like Koch’s. Evidence by other SS wives was collected and presented in the court. The ‘evidence’ also highlighted her ‘reputation’. Anna Reimer deposed: ‘On the other hand it was not unknown to me and also to my women comrades …that Frau Koch already had a bad reputation as a woman at that time’. That is, a set of norms subscribed to by the inmates, the SS wives and the later-day commentators inscribed a certain ‘reputation’ upon Koch.

When such acts of mass violence or genocide are constructed in public, including legal, discourse, a ‘repertoire of behaviours’ – the phrase is Alexandra Przyrembel’s from her study of Ilse Koch – are woven into it, a repertoire that is determined by prevalent social codes regarding gender, and from which we cannot separate how we are shown, understand and consume a Koch or a Grese. Thus women’s crimes in the camps become more pathologised than that of men: they were not ‘normal women’ at all.

When women were implicated, indisputably so, in political violence, they have been consigned to the category of ‘deviant’ humanity, while the male perpetrators remain within the ambit of humanity, but as vile examples of it. This is so because, as the trials and media coverage of Nazi women shows, violence and even cruelty is seen and believed to be integral to the masculine. How many times have we heard rapists and molesters being explained away as ‘boys will be boys’?

‘Does atrocity have a gender?’

Barbara Ehreinrich, pained by the images of Lynndie England, in ‘Feminism’s Assumptions Upended’ mourned:

A certain kind of feminism, or perhaps I should say a certain kind of feminist naivete, died in Abu Ghraib. It was a feminism that saw men as the perpetual perpetrators, women as the perpetual victims and male sexual violence against women as the root of all injustice. Rape has repeatedly been an instrument of war and, to some feminists, it was beginning to look as if war was an extension of rape. There seemed to be at least some evidence that male sexual sadism was connected to our species’ tragic propensity for violence. That was before we had seen female sexual sadism in action.

She then goes on to locate England within a context:

What we have learned from Abu Ghraib, once and for all, is that a uterus is not a substitute for a conscience… Women do not change institutions simply by assimilating into them, only by consciously deciding to fight for change. We need a feminism that teaches a woman to say no – not just to the date rapist or overly insistent boyfriend but, when necessary, to the military or corporate hierarchy within which she finds herself … It is not enough to be equal to men, when the men are acting like beasts. It is not enough to assimilate. We need to create a world worth assimilating into.

Lynndie England Photo: Twitter/@Thatsenough0

Ehreinrich’s finger points to institutional requirements of men and women, especially in fields like the military. While she does not absolve England, she notes that a culture that endorses (masculine) violence also implies that those who assimilate into the culture, begin to embody those same values.

It should be remembered that the Nazi camps were places where no known laws applied – the ‘absolute state of exception’ as Giorgio Agamben termed it – and terror was the sole normative order of the day when it came to the treatment of prisoners. The camp was an instantiation of the genocidal state, its justification. In this genocidal state it was the already circulating ethnic hatred that enabled, welcomed and operated the camps. And this did not need a gender, it assimilated all genders to itself.

Other commentators who have examined the cultural representations of female perpetrators also echo Ehreinrich. Susannah Heschel ponders there is a widely shared assumption that men’s cruelty is, in part, an expression of ‘masculinity, but no exploration into whether women’s acts of cruelty are linked to expressions of their femininity, understanding both terms as social constructs. The realm of the camp belonged to the SS, a male organisation. Did women guards join the realm of power reserved for the SS, or transgress it? ‘

Wendy Lower writes:

For young women, the possibilities for advancement lay in the emerging Nazi empire abroad. They left behind repressive laws, bourgeois mores, and social traditions that made life in Germany regimented and oppressive. Women in the eastern territories witnessed and committed atrocities in a more open system, and as part of what they saw as a professional opportunity and a liberating experience.

Deviant femininity and typical masculinity do not suffice as frames to ‘read’ either Irma Grese or Rudolf Höss (the Auschwitz commandant), but the social, cultural norms of the camp that constructed specific models of behaviour, encouraged certain others – for privilege and power, career and companionship – among both men and women. An entire generation of men and women were ‘lost’ to Nazi ideology, and they gained careers and wealth when they were thus lost.

So, did the camp structure and operations of power draw people in as guards and encourage them to grow into torturers? We find some cues in Sarah Helm’s If This Is A Woman: Inside Ravensbrück: Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women where she writes: ‘Binz’s appetite for cruelty soon made an impression on everyone in the camp. And yet, until she got the job here, she had been little noticed’. Helm adds:

The daughter of a forester, Dorothea Binz was one of several local girls who started work over the summer. These recruits were different to the women who arrived with the prisoners five months earlier … They had no experience of any other penal institution, and many were so young that they had no meaningful experience of life before Nazi rule. Work at the camp was their first job.

And about another guard, she writes:

Langefeld had been as eager as anyone to fulfil Himmler’s edict on ‘protecting the homeland from internal enemies’. The mere sight of women standing for hours in the cold and wet demonstrated her iron discipline.

With no prehistory of violence, placed in a context where power was more or less unlimited, aspiring to greater and better careers, the men, and women, in the camp order quickly assimilated the norms of torture, beating and execution.

Cultures of violence, such as made Nazi Germany a genocidal state, make it possible for perpetrators to emerge even though not all ordinary men, and women, become genocidal. Christopher Browning asks a goose-bump inducing question in his book Ordinary Men: ‘If the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 could become killers under such circumstances, what group of men cannot?’ If we broaden the ambit of Browning’s question, we have an answer to Susannah Heschel’s question on atrocity’s gender.

Impunity and immunity, both bestowed by the structures of power and cultural norms open up the field of violent action, and players seeking to at least enter the field of play need to first sign up, tacitly endorsing the (violent) culture of the field. When we make a genocidal state, there will be demands to enrol as citizens by meeting citizenship requirements of ideology, hate and war-mongering.

It is absurd to ask, as Nazi Germany shows, which gender dominates the genocidal state. It is enough that such a state exists. Build a genocidal state and camps will emerge. Build a genocidal state and there will be men, and women, to run them.

Pramod K. Nayar teaches at the University of Hyderabad.