The Law Should Ensure the Delhi Golf Club Incident is Never Repeated

Perhaps it is time to amend the laws that govern social clubs across the country.

The “governess” from Meghalaya reminded me of the 1980s, when as a 'dependent member' of the then Calcutta’s elite Tollygunge Club, I was determined to flout the newly minted “ayahs and dogs not allowed” notice put up at the swimming pool. Frankly, I was flush with success at having objected to having only the picture of Her Majesty, the Queen in the bar lounge. Truth be told, it was a partial victory; the sovereign was not dethroned, she simply got the Indian president for company, as the club management put up R. Venkataraman’s picture next to her. So I zeroed in on Elmina, the daughter of a tea plantation worker from Jharkhand, who came into our household as a 17-year-old to take care of a one-month-old me, staying on since. I forced the poor thing to defiantly sit at the poolside, while I showed off my dexterity at the deep end of the pool. In a matter of minutes, the club staff, with their invisible “maid detectors”, sniffed out my visibly embarrassed “governess”. Ayahs can’t sit here, they mouthed, hailing from the same class but having to do the master’s bidding almost like a sonderkommando who had to chaperon a fellow Jew into the “shower room” of a concentration camp to be gassed. She is my aunt, I hollered and the staff backed off.

Other than putting Elmina through an ordeal, I achieved pretty much nothing through this adventure. My sense of outrage has also dulled over the decades. I have now become a permanent member of the same club. At least “ayahs and dogs” sounded better than the “Indians and dogs” sign before it.

The “clubs,” with their proverbial dress code norms, are the oases of anachronism that have managed to cling on to the “colonial” legacy, while India around them moved on with its T-shirt-wearing techies. After all, our British masters were sticklers for dressing – no matter that their fancy red uniforms lost King George the American colonies.

Lawyers, for example, adopted the black uniform when the Inns of Court resolved to mourn the death of Mary, Queen of Scots. The only problem is that some bloke forgot to rescind the resolution, and we still mourn Mary in the sweltering heat of Delhi’s Karkardooma or Rohini courts in the peak of summer in black coats and fancy bands.

Even the great reformer Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was denied entry into the governor general’s house to attend a dinner in his honour as he was not in European attire. He then made his point, in a way that only he could, by not only returning in a suit, but also scandalising Calcutta's elite seated at the dinner table, by putting food on his suit. Vidyasagar explained to the governor general – it seems it is my dress that is invited and not I, and so I was feeding my suit.

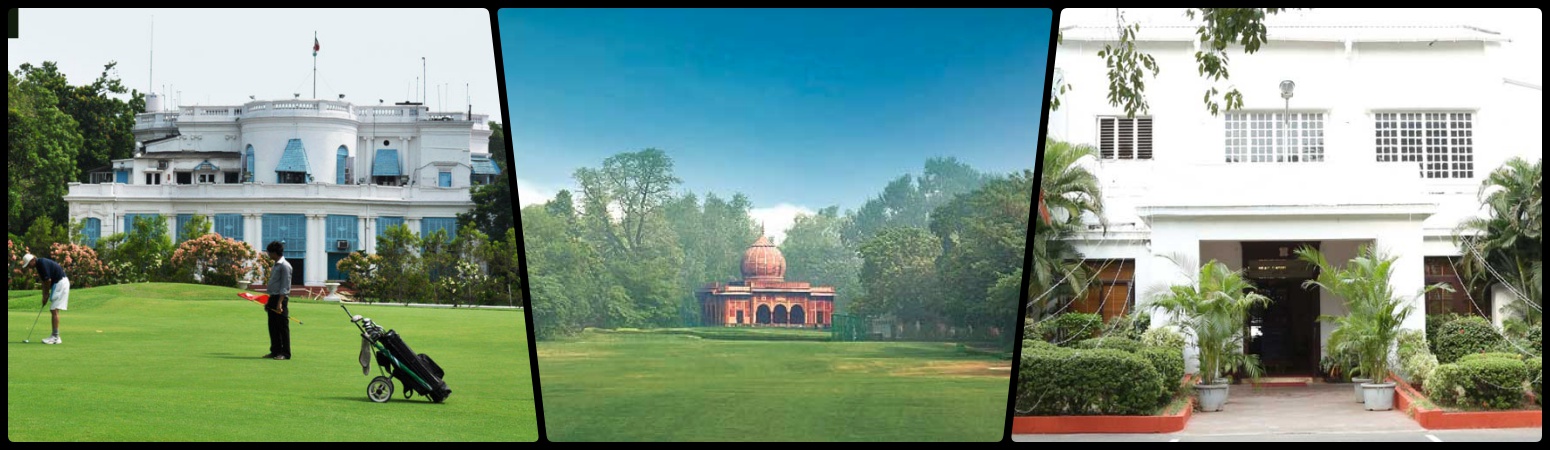

Tailin Lyngdoh’s nightmarish luncheon at the Delhi Golf Club, where her employer, Nivedita Barthakur, had graciously taken her along, only to be singled out among posh Delhiites by her Khasi attire – the Jainsem – which the club staff found “maid like”, really is a wake up call for us.

Is there no law that protects people from such humiliation and discrimination? Do private clubs and societies have a carte blanche to act as they please?

Till now, club related incidents have been episodic and not perceived as serious enough to warrant legal reform. I remember years ago when the Calcutta Club did not permit the legendary M.F. Hussain from entering its hallowed precincts barefoot. In 1982, Shashi Tharoor found himself unable to attend his sister’s reception at the Madras Gymkhana as his silk kurta had no collar. My classmate Nicky Roy was stopped at a Mumbai discotheque in 1996-7 as she was wearing a saree. More recently in 2008 a lady was denied entry into a five star hotel in Mumbai as she was wearing chappals. In 2014, Justice D. Haripanthaman of the Madras high court was denied entry into the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association Club for wearing a dhoti.

It was perhaps this action that spurred Tamil Nadu in 2014 to enact the Tamil Nadu Entry into Public Places (Removal of Restriction on Dress) Act, 2014, which forbade a “recreation club” and others like it from framing rules or circulars which obstructed access for a guest “wearing a veshti (dhoti) reflecting Tamil culture or any other Indian traditional dress”.

There is no denying the fact that people like Lyngdoh are shortchanged by our social attitudes. We educated Indians who so proudly boast to our NRI cousins that we prefer India, with its garbage, pollution and corruption notwithstanding, as we have maids who do our dishes, cooks who make our meals and drivers who drive our cars. Legally, however, Lyngdoh can only point a finger at our constitutional silence and obsession with the public. Careful examination of the fundamental rights in chapter three of our constitution reveals that the primary focus of the framers was to regulate and control “state” power and infraction into personal rights. The significant exception being the “right against exploitation” addressed by Article 23, which targets private practices such as “begar”, and of course the abolition of the practice of “untouchability” in Article 17. Even Article 15, which prohibits discrimination on grounds “only” of “religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth”, confines the protection to “access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment”. Private clubs are given a complete miss.

This is further compounded by the fact that unlike many countries such as the US, India does not have a civil rights law that addresses discrimination in private spheres such as employment and in private societies or clubs. Until the Supreme Court intervened in the Vishaka case (1996), there was absolutely no protection against gender discrimination in employment. Even these guidelines only addressed “sexual harassment” and not other forms of gender based discrimination. Perhaps the only group that has been given some access to a civil rights protection, are the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, for whom a special legislation was enacted in 1955 – the Protection of Civil Rights Act, which was reinvented in 1989 as the SC/ST Prevention of Commission of Atrocities Act.

There are many global precedents. In 1944, the King’s bench held the Imperial Hotel liable for turning away an Afro-Caribbean British subject, Constantine. After Britain joined the European Community (EC), the protection of the Human Rights Charter of the EC has only strengthened its legal position.

Across the Atlantic, in 1994, Denny’s, a chain restaurant in the US, reportedly paid millions to settle the claims of black customers who said that they were discriminated against by Denny’s staff, and were forced to wait longer and pay more than the white customers. In 1999, a Canadian Court ruled in favour of one Ms Carpenter, who was denied entry into a nightclub on account of her aboriginal ancestry.

The march of the law in India, sadly, has not kept pace. In fact, some developments have been retrograde. In 2005, in the Zoroastrian Cooperatve Housing Society case, the Supreme Court was called upon to decide whether a private housing society could restrict its membership only to Parsis. The court observed that “it is true that in secular India it may be somewhat retrograde to conceive of cooperative societies confined to a group of members or followers of a particular religion, a particular mode of life, a particular persuasion.” However, it then proceeded to hold that this did not mean that a society cannot cater to parochial sentiments. By applying the test to determine whether a body has a “public” character and hence obligated to apply the non-discrimination stipulation of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, the court held that the society was a “private” body. So, it could do as it pleased, as it was not obligated to give effect to the constitutional guarantee against “non-discrimination”.

There is no denying that private clubs must have a measure of autonomy to preserve their culture or ethos or tradition or customs. People will be willing to give an arm and a leg for entry, as membership to such clubs in Delhi and other metros is tough to come by, and the waiting time for applicants sometimes runs into decades. At the same time, one cannot run away from the proposition that such clubs cannot be islands that rebuff the writ of our constitution and rule of law.

Tamil Nadu has attempted the legislative route. Other models can be examined – such as amending the Societies Registration Act, the local shops and establishment law and excise rules, so that registration and recognition of such societies and clubs would have to be on conditions that would ensure that no Khasi sister of ours would ever again be humiliated in any club in this country.

Sanjoy Ghose is a Delhi-based lawyer.

This article went live on June twenty-ninth, two thousand seventeen, at zero minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.