The six-week-long Maha Kumbh Mela, held in Uttar Pradesh’s Prayagraj, came to a close on Wednesday, February 26. The same evening, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting released a statement that the festival drew a total crowd of over 66 crore or 660 million since it began on January 13.

That makes it the biggest mass gathering of spiritual nature across the world. For years now, the Kumbh (meaning pitcher) Melas have been a sight to behold. From foreign tourists and devotees to naked, ash-smeared ascetics with matted hair, whose whereabouts otherwise remain unknown, everyone flocks to the festival for a taste of the mythical Amrit.

According to Hindu mythology, the ‘Kumbh’ was a pot or pitcher containing Amrit or the potion of immortality, which became the bone of contention between gods and demons. To protect this Kumbh from falling into the wrong hands, the deities fled with it. As a result, drops of the immortal nectar fell at four places. In modern India, these locations are Prayagraj, Haridwar, Ujjain and Nasik where different iterations of the Kumbh Mela are held on a rotational basis. All the four sites are close to river banks and Hindu devotees believe that bathing in the sacred rivers at these locations during the Kumbh festival absolves one of their sins and brings them closer to moksha (freedom from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth) and immortality.

Note that the Kumbh’s origin tales, its religious significance and how the site for the Mela is decided are historically contested and vary from text to text or which historian or astrologer one speaks to. The bottom line is that the main Kumbh Mela or the Purna Kumbh (full Kumbh) is held once every 12 years while the halfway edition happens every 6 years, which is called the Ardh Kumbh (half Kumbh). In 2017, Uttar Pradesh chief minister Adityanath, a self-styled monk who uses the title Yogi, had renamed the Purna Kumbh as Maha Kumbh. The Ardh Kumbh was rechristened to just Kumbh. The nomenclature was reportedly changed to bolster the importance of the Ardh Kumbh in 2019 and ascribe even greater significance to the 2025 ‘Maha’ Kumbh.

The scale of the Maha Kumbh Mela this year was certainly unparalleled. The 2019 Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj drew a crowd of 25 crore or 250 million. The 2013 Maha Kumbh Mela, also in Prayagraj (then Allahabad) had 12 crore or 120 million attendees. Both significantly lesser than this year’s turnout, based on government figures. Much of this was because this year’s Maha Kumbh Mela was considered an even greater, once-in-a-lifetime affair that happens only once in 144 years.

But even if spread over 45 days, 66 crore attendees is a very, very large number. A key question here is, how did so many people make it to Prayagraj?

Arriving at the Maha Kumbh Mela

There are primarily four ways to reach Prayagraj: (1) By flights, (2) by trains, (3) by buses and (4) by private cars or cabs. Tracking the first three types is relatively easy since travellers have to buy tickets against their reservations and those can easily be accounted for.

(1) Finding data on the number of people who took flights was relatively simple. According to a Hindustan Times report from February 28, citing data from the Prayagraj Airport, 5,60,174 people travelled by air on 5,225 flights between January 11 and February 26.

(2) Data on those who took trains was also publicly issued. On February 27, railways minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said 17,152 trains carried passengers to the Maha Kumbh Mela. “The total number of pilgrims attending Maha Kumbh stood at 66 crore, with 4.24 crore passengers handled at the nine key railway stations of Prayagraj alone,” he added. Now, it’s possible that more people took the train to other cities close to Prayagraj and then reached the Maha Kumbh Mela using cars, cabs or buses. Since it’s difficult to determine which stations these people took trains to, let’s count them among those who reached via road transport.

(3) Accounting for the number of visitors who came via buses was a challenge since the government did not give a consolidated number of how many attendees used bus services to reach Prayagraj from other cities or states. This should have been easy since most state bus operators have this data, but neither the central government nor the state road transport corporations, barring UP, made this information public.

A press statement by the Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (UPSRTC) dated March 6 said that “3.25 crore people were taken to their destination” during the Maha Kumbh using UPSRTC services. It’s not clear whether these are to-and-fro tickets or just account for everyone who was taken to the Maha Kumbh site. But for simplicity’s sake, let’s assume it’s the latter.

Alt News reached out to several other state transport bodies. Among them, Gujarat State Road Transport Corporation responded to our queries and told us that 5,978 travellers used GSRTC services.

Private bus operators too have not made public data on how many travellers used these buses to go to Prayagraj. But a report by business publication Moneycontrol citing the founder of a deep tech start-up focused on AI solutions for transportation put the average daily number of travellers taking private buses to Prayagraj at 6 lakh. Over 45 days, that comes up to 2.7 crore.

(4) Coming to the last way to reach Prayagraj, i.e. via private cars or cabs. The only way to determine how many vehicles entered Prayagraj during the Maha Kumbh Mela is through toll data or highway cameras, for which, again, the government has not released any data or statistics so far.

So, here’s what we know so far:

Kumbh arrivals by different modes of transportation. Photo: AltNews

Attendees who came by flights: 5.6 lakh

By trains: 4.24 crore

Using UPSRTC buses: 3.25 crore

Using GSRTC buses: 5,798

Using private buses (estimation): 2.7 crore

Using other state-controlled buses: No data

By cars/ cabs/ bikes: No data

Total attendees accounted for: 10.25 crore

Govt estimate of attendees: 66 crore

Remaining: 55.75 crore

This means that we have no data on how 55.75 crore attendees, which is roughly 85% of the official visitor count, came to Prayagraj, which comes as a bit of a surprise since this information is not particularly difficult to track. Entry and exit points in a city usually have toll booths and cameras, and buses too need permits to enter states, which means authorities can track this information. Why it hasn’t been made public yet is anyone’s guess.

That brings us to the next point. How believable is this 66-crore figure?

The number of Kumbh attendees accounted for is far lesser than the official number of attendees. Photo: AltNews

If 660 million people visited the Kumbh this year, it would mean that over 45 days, part of Prayagraj witnessed an inflow of people which is nearly twice the population of the United States, as the Prime Minister himself said.

Number of Kumbh attendees compared to the population of the United States.

Note that the area designated for the Maha Kumbh Mela is 4,000 hectares or 40 square kilometres. In comparison, the US has an area of 9.8 million square kilometres.

India’s estimated population is about 140 crore or 1.4 billion, although this could be higher now since the decennial Census did not take place since 2011. But going by official numbers, nearly every second person in India or almost half the country attended the religious gathering. This seems a little difficult to believe.

Photo: AltNews

Also, 79% of the Indian population, which comes up to 1.1 billion, are Hindus, according to projections by Pew Research Center. This means that, every Hindu family of, say, 5 people, sent at least 3 members to the Kumbh.

The number of Hindus said to have attended the festival. Photo: AltNews

Based on 2011 Census figures, the most populated state in India is Uttar Pradesh (19.98 crore people), followed by Maharashtra (11.24 crore), Bihar (10.41 crore), West Bengal (9.13) and Madhya Pradesh (7.27 crore). These five states have a combined population of about 58 crore or 580 million. So, this means that in 45 days, the number of people visiting the Maha Kumbh Mela, in a part of a city in Uttar Pradesh, surpassed the population of India’s five most populated states.

Kumbh attendees vs state populations. Photo: AltNews

Here are more comparisons. Asia’s largest slum, Dharavi, is home to a million people. The number of Kumbh visitors through the 45 days was 660 times the population of Dharavi.

This also brings us to the next question, how did the government account for 66 crore people then?

How Were 66 Crore People Counted?

It is important to note that the government’s press statement does not specify whether 66 crore people came to the Maha Kumbh Mela or 66 crore entries were recorded.

This is a crucial difference. If it recorded 66 crore or 660 million entries, that could account for duplications as well. For example, the same person entering the Mela on all 45 days would be recorded as 45 entries or visits. Or one person entering and exiting the festival 10 times a day would be 10 entries, multiply that by as many days this person stayed and so on and so forth.

However, going by the language of the government’s press statement, it is likely that footfall numbers refer to visitors not merely entries:

“The expected turnout of 45 crore devotees in 45 days was exceeded within a month, reaching 66 crores+ by the concluding day”

But how it managed to count these devotees remains shrouded in mystery.

Alt News spoke to several attendees who told us that there was no particular entry or exit gate and people could enter the Mela Kshetra (a temporary settlement by the river bank set up by the state government) or the Sangam ghat from several places. As such, visitor entry was not being manually monitored.

But media statements by the government say that advanced artificial intelligence-based cameras and drones were used to monitor crowd density and alert the Integrated Command and Control Center to prevent mishaps owing to overcrowding, flag suspicious activities and spring to action in case of emergencies like fire.

According to an India Today report, AI-based predictive modelling was used for crowd counting and monitoring crowd density. To do so, 1,700 cameras were installed across strategic locations at the mela premises, with 500 AI-powered cameras for real-time crowd analytics. However, the report, citing IPS Amit Kumar, in charge of the Integrated Command and Control Center at Prayagraj, warned that advanced AI models can be limited. “… There is a probability that the same individual could be counted multiple times if they visit the ghats on different days.” We don’t know yet if the government’s estimate of visitors accounts for such duplications.

Alt News reached out to Rijul Singh, an AI developer who has worked on crowd tracking models to understand how such processes work. He explained that the simplest way is perhaps a detection model, wherein the algorithm can detect each person in a picture based on identifiable characteristics such as their face. These detections are counted to give an accurate number of people that are visible in the frame. However, in very large crowds, this may not work very well because people who are obscured or whose faces do not appear clearly will not be counted. In crowds as large as the numbers we are seeing for the Maha Kumbh Mela, it might be even harder because the density is very, very high. You might see the head of a person, a hand or a leg, but the algorithm will not count that as a person, Singh says. “Detection models fail if everyone can’t be seen clearly in the frame,” he adds.

Then there’s the crowd density estimation model where you feed the AI model a certain dataset, say, images, and give the output, mentioning how many people can be seen in those images, Singh says. It uses these examples to learn and analyse and then estimate or approximately predict how many people can be there in a crowd if you give it a fresh set of images. “These are not very accurate but they can deal with large crowds and are better to use when you can’t see people very clearly or there are occlusions.” However, this model can give you an estimation of crowd density, it is not very feasible if you want to track unique visitors.

On facial recognition being used, Singh said that he wasn’t sure how feasible it would be to track and maintain a database of 66 crore people, considering the number refers to unique attendees, especially if there are no fixed or designated entry points. “So, there is a very good chance that there could be many duplicates,” he mentions before adding that AI can just give you a broad number, the algorithm that is used to process that data and then come to the unique visitor count is what is crucial.

On whether it is possible to combine facial detection and crowd density estimations to arrive at the unique number of visitors, Singh says that it could be possible but with a huge margin of error since the data itself is estimated based on AI.

“Current models can’t be so precise and accurate with such large numbers and uniquely identifying people of the same ethnicity who may belong to the same demographic and could be wearing similar clothes is a big challenge,” he says, adding that most current state-of-the-art, open-source models would fail to accomplish this. Also, most cameras, especially CCTV cameras, are in fixed positions and capture people only at certain angles so you don’t end up seeing a large percentage of the faces. “Even if you do manage to capture their faces, if you zoom in, it will be distorted and you won’t get a very precise close-up of a person’s face to be able to track so many people.” There will be a margin of error, whatever algorithm is used, we just need to know how much that is, he reiterates. When asked about the many drone cameras that are deployed, Singh said that those capture top views and wouldn’t be able to capture facial features unless people look up and reveal their faces to the camera.

It would be charitable to say that the government figure of 66 crore attendees, which it claims are tracked by artificial intelligence-based technologies, seems a bit of a stretch.

The reason we highlight this is because the Kumbh Mela, meant to be a religious, spiritual gathering under the guidance of the Sadhus and their Akhadas, has over the years, turned into a political tool used by parties for marketing.

Interestingly, the footfall data comes on the heels of a recent report by a venture-capital firm, which says that a billion of the country’s 1.4 billion do not have incomes that allow them to spend on discretionary goods or services. Also astonishing is the speed at which the I&B ministry released this visitor count—the same evening the festival ended. This is in sharp contrast with how much time it took the administration to share information on how many were affected in the stampedes that took place at the site of the Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj and the New Delhi Railway Station.

The Desperation to Suppress Stampede Toll

On the intervening night of January 28 and 29, after the Mauni Amavasya had set in (an important day of religious significance according to the Hindu calendar), thousands rushed to take a ritual bath at the Triveni Sangam — the confluence of rivers Ganga, Yamuna and the mythical Saraswati.

Around 2 am, a stampede broke out near the Sangam ghat. Until the wee hours of the morning, no official representing the government or the police clarified what happened and how bad the situation was.

For hours after the mishap, police officials and Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adityanath denied that any major event had even happened at the Maha Kumbh mela.

Around 5 am, the special executive officer overseeing the Kumbh said that it was a “stampede-like situation” and there was nothing serious. At 8 am on January 29, the chief minister even posted on X that holy baths across the Sangam were going on peacefully.

The Prime Minister offered condolences around midday (11.47 am), but to make matter worse, even after the PM’s condolence tweet, Kumbh Mela SSP Rajesh Dwivedi told the media (12.05 pm) that no stampede had taken place, and some devotees were injured due to the large crowd that had gathered there. He also stated that people should not pay attention to any rumours. Minutes later, (12.23 pm) President Draupadi Murmu tweeted to express her condolences to the kin of the victims.

Finally, almost 17 hours later, at 6.39 pm, DIG Mahakumbh Vaibhav Krishna issued a statement that 30 people had died while 60 were injured in the mishap.

One of the survivors from Bihar who lost their mother-in-law in the stampede told BBC that she was handed over her body in the afternoon of January 29 along with a sum of Rs 15,000. The amount is a measly fraction of the compensation announced by the government, but shows that the state was aware of deaths by afternoon, but chose not to make a public statement till evening that day.

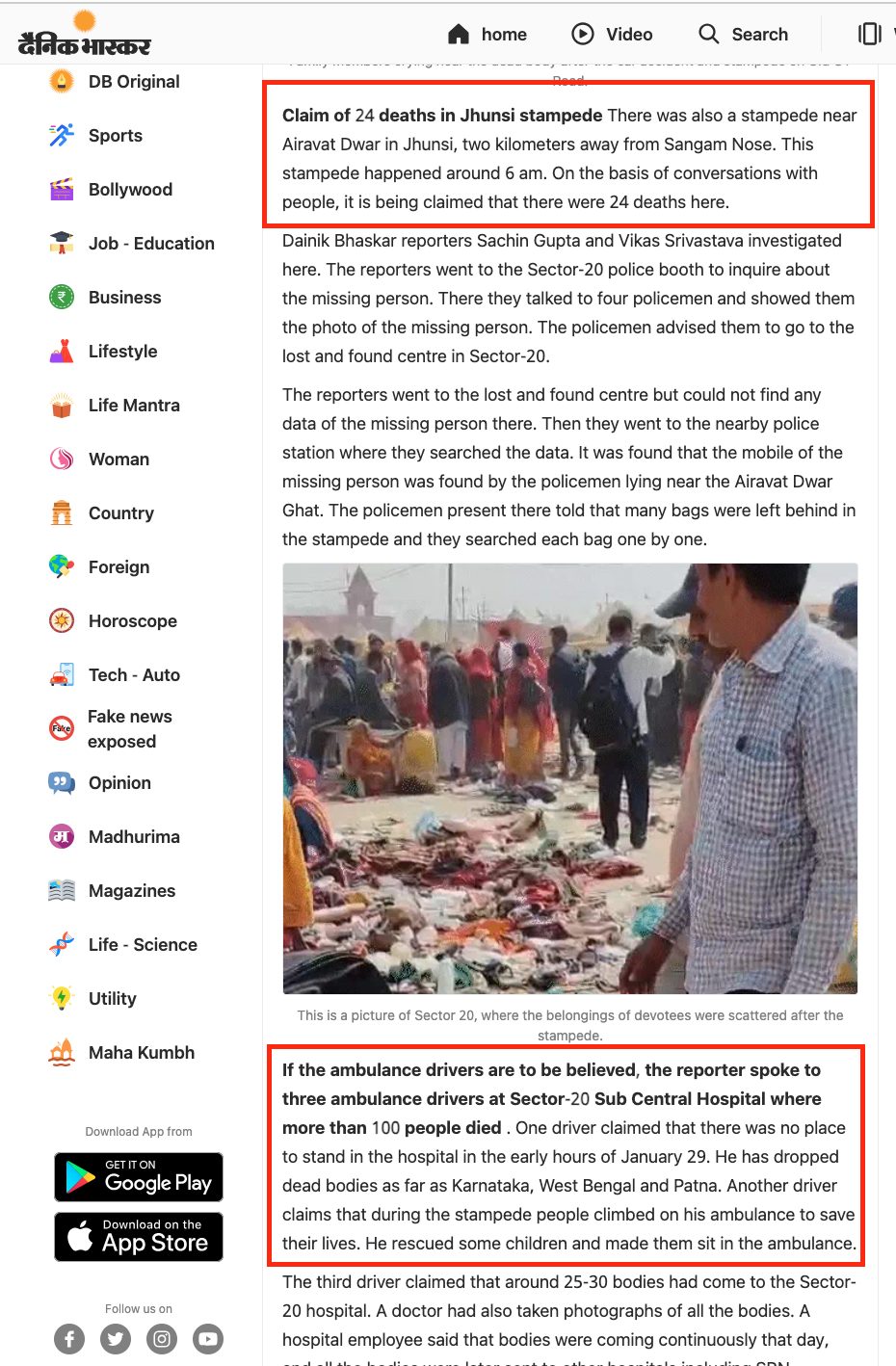

And this is the story of just one stampede. Two more stampedes had taken place in the Maha Kumbh Mela premises. One near Jhusi and the other in Sector 10 near the old GT Road. On Jhusi’s stampede, the police initially said nothing and clarified much later that seven people, including a child, were killed. The Lallantop’s video report from Jhusi the following night shows how tractors, cleaning crew and others began clearing out all signs of the stampede with a lot of urgency.

A ground report by Dainik Bhaskar on February 1 said that at least 24 deaths took place in Jhusi, however, the number could be 100 or more based on testimonies of ambulance drivers.

There is hardly any word on the third stampede. A Deccan Herald report said that seven women lost their lives in the third crush.

A similar incident also took place at the New Delhi Railway Station (NDLS) on February 15 around 9:30 pm, where travellers heading to the Maha Kumbh were crushed as crowds swelled. Like in the case of the Prayagraj stampedes, the authorities first completely denied anything happened. The first reports of death (15 casualties) came only after midnight. Videos and photographs of the rush and piled up bodies on X seemed to indicate that the death toll and number of those injured could be higher.

A Hindu reporter’s account of the NDLS stampede paints a worrying picture regarding the numbers being publicised and the ground reality:

“… Conflicting statements made it a challenging task for journalists working for national dailies. Our deadline was looming, but authorities continued to underplay the situation hours after it occurred, which meant that we could not communicate the facts of the night. As a result, readers across India woke up the next morning to multiple newspapers carrying headlines that did not confirm the number of casualties… In sharp contrast to the speed in communicating factually correct information was the speed with which post-mortems were carried out that night… At the station too, urgency dictated the mood: all the markers of a stampede — shoes, garment pieces, and blood marks — were removed or scrubbed off.”

Interestingly, on February 21, Hindustan Times reported that the government asked social media platform X to remove all videos related to the NDLS stampede.

On January 29, a story by Dainik Bhaskar said that the toll in the Prayagraj stampede was between 35 and 40. A few days later, it published a detailed investigation outlining the gaps in the authorities’ claims on the death toll. The outlet’s findings seem to indicate that the toll could be anywhere between 41 and 61.

Last month, Newslaundry published a detailed story, based on police records, that at least 79 died in the Kumbh stampedes. The news outlet’s report suggests that many stampede deaths were also passed off as deaths due to natural causes in the absence of timely postmortems.

We are not the first ones to say that something in this entire episode is amiss. Ground reports mentioned above and others have consistently pointed out the gaps in the official data on toll and injuries.

But the BJP-led government built two different kinds of narratives with official numbers. One, that the regime managed to execute a Hindu festival uniting crores of devotees. Two, the mishaps, if at all they happened, were infinitesimal both in magnitude and gravity.

That brings us to the last bit. What was behind the maddening rush to visit the Kumbh Mela?

A ‘144-year’ wait

Turns out many wanted to be part of the once-in-a-lifetime religious event just because the next one would be after 144 years. Some of the devotees Alt News spoke to gave the same reason. They said that they hadn’t considered going to the Kumbh in the previous editions but came to this one only because it was taking place after 144 years and there’s no way they would get a chance to do this again.

They are not to be blamed. This year’s Maha Kumbh was widely marketed by the BJP government as such.

The narrative was further amplified by ministers, religious leaders and used verbatim even by most Indian and global news outlets. Here are some screenshots.

The reason for this being a rare event was attributed to a unique celestial alignment. Now, celestial alignments and astrology are a belief system we don’t wish to counter. However, this is not the first time an edition of the Kumbh mela was advertised as being a rare occurrence that happens once in 144 years.

Yes. We went through several news reports, government records, as well as academic papers, which referred to the 2001 and the 2013 Kumbhs as a once-in-144-years event.

A performance audit report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on the 2013 Maha Kumbh mela clarifies that the Maha Kumbh takes place every 144 years, the Purna Kumbh every 12 years and the Ardha Kumbh every six years. It referred to the 2013 mela as the Maha Kumbh.

As we said at the beginning, the nomenclature of Purna and Ardh Kumbhs was changed by Adityanath in in 2017. So every Purna Kumbh after 2017 would be a Maha Kumbh.

A 2024 research article on Springer, titled “Cultural heritage and urban morphology: land use transformation in ‘Kumbh Mela’ of Prayagraj, India” referred to the 2001 Kumbh mela in Prayagraj as the Maha Kumbh taking place once every 144 years.

Another research paper on the comparative study of Kumbh melas at Allahabad and Nasik, published in a 2016 compilation of presentations at the Urban Heritage and Sustainable Infrastructure Development conference, said, “The city of Allahabad successfully hosted the second Kumbh of this century and a festival that would return only after 144 years – the Mahakumbh in 2013.”

A 2013 article in the International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications also dubbed the 2013 mela as one taking place after 144 years.

Many more such examples can be found.

We also dug up archives of news outlets and found an ABC News report from 2001 on the Dalai Lama visiting the Kumbh Mela. An explanatory paragraph in the story said:

“A festival official said more than 50 million worshippers hadvisited by late today, and more continued to arrive, drawn by anauspicious astral arrangement that Hindu astrologers say coincideswith the Kumbh only once in 144 years. The festival began January 9 and is held every 12 years.”

An Economic Times news report from January 2013, said that holiday operators had to up their offerings for the Kumbh Mela that year, “which is extra special this year because it is the Maha Kumbh that comes once in 144 years.”

We also found a Newsweek report from 2013 and an archived page from 2013 in The New York Times on the stampede at the then Kumbh mela. Both these also made the 144-year mention.